Confessions of a Former Food Segregationist In search of culinary roots

by Regina N. Bradley

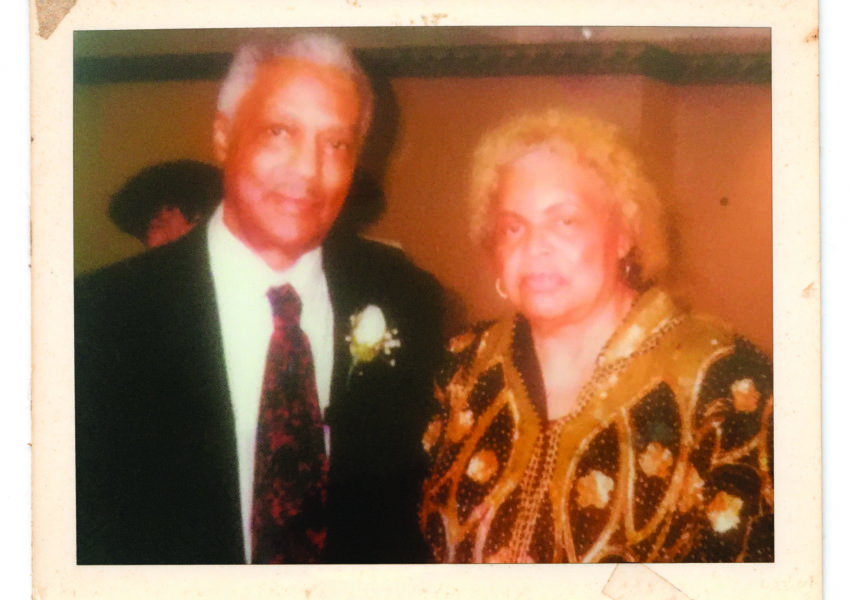

One of the things I miss most about my daddy is our weekly Sunday argument about food. Daddy lived in a house which my grandfather, whom I called Paw Paw, built when I was a toddler. Daddy was a reverend and car salesman, and ripped and ran as much as I did. Sundays were for church, family, football, and big dinners. After church, we’d come home and tear off itchy stockings, tailored suit jackets, skirts, and dresses. If the spirit moved me, I took a nap. Sunday naps are the best sleep.

![]()

Nana Boo cooked the majority of Sunday dinner the night before while watching Precious Memories. She waited to make the cornbread until Sunday. We had a regular dinner rotation: cubed steak or streak o’ lean (we called it “skin meat”), cabbage or collard greens, fried squash or black-eyed peas, and cornbread. While the cornbread fried, Daddy and I assumed our positions to fuss at each other. I perched on the third barstool closest to the wall, and Daddy stood in the corner of the bar in front of the lower cabinet where Nana Boo kept the condiments. He crouched under the light and rested his elbows on the bar to look me in the face. He sized up my plate and snickered.

“You know your mama messed up your taste buds, right?” Daddy watched me as he expertly cut half an onion into slivers for his collard greens. He didn’t look down once. This was his opening argument.

I wrinkled my nose and turned in my seat. The stool squeaked in protest. I made sure to avoid hitting the corner of the kitchen bar, where the broken tiles already looked like a child missing her front teeth. The sucking sound of the knife tearing through onion hovered between us. I sighed, loudly, to let him know I was ready for battle. “Daddy, leave me ’lone.” I puckered my lips and smacked my mouth. “Mommy didn’t mess up nothing,” I said.

I think about food as a sort of genealogy, an act that remembers loved ones and keeps communities alive.

Daddy laughed and pointed to my plate. It was neatly compartmentalized into sections: meat, greens, and room for fresh cornbread. The sound of Nana’s iron skillet sizzled behind Daddy. Our stomachs growled in unison. In one swoop, Daddy swept his fork across the plate and shoveled a mash-up of collards, onions, and fried cube steak. With a full mouth, he said, “What kind of Southern girl eats her food one little piece at a time?” He called me a food segregationist.

I winced and picked at my steak. Nana Boo pushed a hot plate of jailhouse cornbread in front of us. The steam slapped and licked my chin and cheeks. “Daddy, reach ’round there and give me the pepper juice, please?” He fumbled in the lower cabinet filled with condiments and passed me the red-capped bottle of vinegar and peppers. Daddy didn’t let up.

“Our food is supposed to touch!” He shoveled another forkful of country mash into his mouth.

I pushed past my dad’s large hand to pick the crustiest piece of cornbread. He laughed and nodded in submission. I pinched off a piece and swirled it in the spreading pool of collard green juice on my plate. “At least you know how to sop,” he chuckled.

Now, when I recall Daddy’s weekly ribbing, I think about food as a sort of genealogy, an act that remembers loved ones and keeps communities alive. My grandmother told stories about her family through how she made her cornbread, and my dad shared stories of his childhood through how he ate it. I’ve reframed my definition of family through the way we ate. Indeed, if I was a food segregationist, perhaps it was genetic: I saw firsthand that my mom hated for any of her food to touch. But if my taste buds were as hijacked as Daddy said they were, that was his fault as well as hers.

They met while stationed on a Naval base in Hawaii, where I was born. While I don’t remember much about my earlier tastes, I do remember I was exposed to a variety of foods because I was taken care of by a little bit of everybody: Filipino, black, Latino, white, and “we don’t know where they from” folks. Lumpia. Sweet milk and rice. Spam musubi. Through food—and Sesame Street—I learned to appreciate diversity.

In the black South, food is the foundation for defining what is and what ain’t Southern.

Even with my eclectic taste buds, there was a common denominator: the South. My daddy’s people are from Georgia. My mommy’s people on her daddy’s side are from Mississippi. I never knew my Opa, but he is grounded in my memory because of the stories my uncles and mommy told me about what he used to eat. Opa was a mysterious black man from Yazoo City, Mississippi, who got the hell out of the Delta for reasons all his own. He landed in Chicago, then Germany, where he met my white grandmother, and finally retired from the military in northern California outside of Oakland. With each move, he kept the South on his plate. Opa ate squirrel and raccoon—“the one with the mask,” as my Oma described it—and encouraged his biracial children to do the same. I consider my mom Southern by affiliation. Though she has traveled the world two or three times over, her food choices call her out as a country girl. She loves chitlins, pig feet, and gizzards. On the rare occasions my mom visited us in Albany, Georgia, Maryland Fried Chicken was her favorite (and often first) stop. They have the best livers—fried hard, of course—and fried tomatoes. Mommy went straight for the extra-crispy gizzards. She’d let out a squeal of joy as the box wet itself from the steam seeping from beneath the lid.

In the black South, food is the foundation for defining what is and what ain’t Southern. Goodie Mob’s 1995 album Soul Food employed cooking metaphors to narrate the experience of being young, poor, and black in post–civil rights Atlanta. Culinary interpreter Michael Twitty uses food to explore African American identity. Additionally, culinary genealogies of Southern black folks continue to flourish and branch out of the region and into the world. Edouardo Jordan’s new restaurant, JuneBaby, in Seattle, Washington, pays tribute to his Florida upbringing and deliberately reclaims Afrocentric foods in the restaurant sphere.

In my own kitchen, I keep the legacy of Nana Boo’s jailhouse cornbread and Daddy’s expert onion-cutting skills alive. My husband, Roy, also a military brat from Valdosta, Georgia, brings his culinary genealogies rooted in Arkansas and south Florida to our table. His love of barrel grills, fresh pork rinds and hot sauce, and spicy deer sausage blends well with my Georgia and Mississippi roots. Among our many culinary debates, the one about what to call scuppernong grapes is most legendary. My folks called them “scuplins,” and Roy’s family called them “bullets.” Nana Boo squashed the argument with a laugh and wave of her hand, declaring both names acceptable.

As I continue to explore what food means as a preserver and amplifier of Southern black identities, I think back fondly to my Daddy, my Opa, and what we shared across our plates.

Regina N. Bradley is an incoming assistant professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at Kennesaw State University. She is the author of a short story collection, Boondock Kollage: Stories from the Hip Hop South.