Foraging We recalled the sweetness we left behind.

by Janice N. Harrington

illustrations by Dèsirèe Kelly

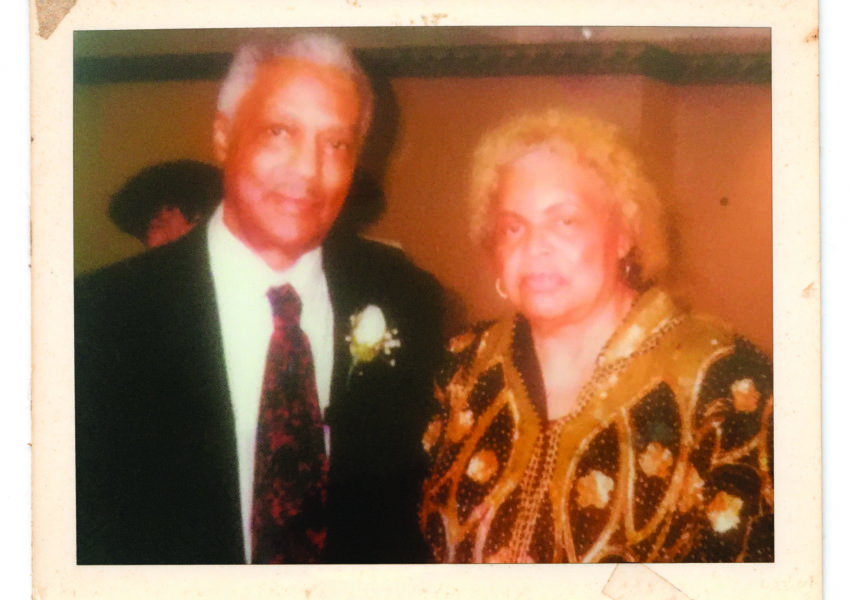

![]()

I come from foragers. Southerners who hunted and fished, and who knew where to find blackberries, wild grapes (muscadimes), walnuts, pokeweed, and persimmons.

I learned as a child that if I used my eyes, if I was patient, if I risked welts and itchies and mosquitoes, I would be rewarded with sweetness, with mason jars filled with wild fruits, with store for hard times. I knew that foraging made us generous. Child, you go ahead and take some of that with you. We sure can’t eat it all. We plucked and picked and gathered. Every season had its fruit and its difficult arithmetic. How many berries to put in the bucket and how many to put in your mouth? I received my first lessons in ecology and conservation beside the banks of creeks, in weedy thickets, under the boughs of forgotten orchards. When my family travelled north, we continued to forage and fish. Food was expensive for a young family. My mother gardened and canned, but not for recreation. We foraged—yes, for good, free food. But we foraged more because it was who we were, how we could recall the sweetness we left behind. We foraged because of the pleasure we found in gathering secret treasure. And always, afterwards, we had—not just wild berries, or fruit, or nuts—but also a memory: a necessary food.

Muscadines

Alabama, 1962

![]()

Dishpans, lard buckets, bushel baskets, we went out—cousins, aunts, uncles, elders—to search for muscadimes, wild grapes threaded around pines. We walked through the brambles searching for the bruise-colored fruit, small as knuckles and acid-sweet. We brought them home sun-warm to wash with well water, boil and sugar into jelly, or smash-pop against the tongue, so acidic they burned and scalded our lips. Purple-black, blue-black, ink-black grapes—we hummed around their vines like gnats and bees. Laughter and Black voices rising from a pine thicket; warm, pine-scented air mixing with the winey smell of wild grapes; muscadimes dropped into a lard tin or a washpan or into waiting hands. We went out together and came back the same way.

Poke Salad

Alabama, 1963

![]()

I didn’t like it then. American nightshade, poke sallet, pokeberry, pokeroot, pokeweed, skoke, Virginia poke, pigeon berry, inkberry. Poke salad mixed with egg and scrambled. Anna walking beside a seam of red dirt looking for the large green leaves and purpled berries. How did she fix it? We were poor then, Websta’s gal and her baby girl. Mama, she said, fixed it all the time. Back there, pokeweed was plentiful. How to fix pokeweed: Wash the leaves carefully. Tuck the leaves into cold water and boil. Drain off the water. Heat bacon grease in a skillet. Add pokeweed and a touch of sugar. Scramble in egg. Serve hot. Or add pepper sauce and eat it like spinach.

Sand Plums

Nebraska, 1964–1969

Nebraska—long, rolling hills, red cedars, open pastures, barbed wire—and we were a Negro family taking a Sunday drive. I remember the sunlight, the sweeps and panorama of black mud and mud-matted angus. High summer or maybe fall. It was a clear day and warm. Anna saw them first and recognized what they were: sand plums, sun-colored, large as quail eggs, memory says. Charles pulled over and Anna scrambled across the ditch and climbed the weedy embankment to lean and stretch over barbed-wire spurs to pluck sand plums, dropping them into the basin of her upturned hem. The grove buzzed with yellowjackets and flies. Anna cried out, stumbling down the bank, and we could see the shiny ribbon winding red and red and red down her yella thigh. A barbed spur had slit her skin. Her flesh burst apart, as ripe plums do. We picked no more but brought the bounty home. Juice on our fingers, our cheeks, sweet liquor, liquid light. Anna made jelly from them, danger and sweetness saved in a mason jar— plum jelly to stay winter and kindle sunless days with light.

Morels

Nebraska, Late 1970s

![]()

Wayne and I were heading out on his motorcycle somewhere above Omaha to search for morels.

Hickory chickens, molly moochers, merkels, sponge mushrooms. By whatever name, morels were the holy grail for mushroom hunters. I was smitten by their mystery.

A fungus that tasted like nothing else.

Wayne drove north. I no longer remember the exact where or the exact route. We rode his motorcycle—a Norton, I think. I sat behind, as I always did, with my arms wrapped around Wayne’s side. I watched the scenery blur, hoped that no errant bee or wasp found its way up my sleeve, while I listened to the drone of our engine and the steady rumble of the road. Wayne said he liked motorcycles for the sense of freedom they gave him. I hardly equated cars with claustrophobia, and I thought that the sky I saw through any windshield was sky enough. Despite the discomfort and fishbowl exposure, I squeezed myself between his rump and the back end of the cycle and held on.

We sped fast through Nebraska countryside, a mixed-race couple, driving toward some likely wood that Wayne knew about where we might find morels. We passed a farmhouse and throttled through a tunnel of trees, when the motorcycle wrenched violently to one side. It was one of those moments when you suddenly see everything at once. Time slowed and time sped by. I saw what I thought would happen: the motorcycle slamming against the asphalt, sparks spewing from the throat of the exhaust pipe. I saw my body in free fall, my helmet ramming against the road, and Wayne’s body folding into a broken heap. I saw the now when an arrow—an arrow someone had aimed, and which Wayne had jerked the bike to miss—passed between our tires. I saw the long, yellow shaft (thick around as my little finger), heard it rattle against the asphalt, followed it mentally into what next and after.

The motorcycle shuddered, wavered. My hands tightened on Wayne’s ribs. The arrow skidded onto the shoulder. Wayne fought the wheels, straightened the cycle, and drove on, both of us relieved. Morels, I learned later, have another common name—miracles.

Did someone see my brown arms wrapped around Wayne’s body? My brown face through the helmet’s visor? Answers are like mushrooms. Some are poisonous. Others are too difficult to know for certain.

Blackberries

Louisiana, 1989

![]()

My marriage ended. “A mistake,” my ex said, along with several other complaints about my deficiencies as a wife. But loving badly doesn’t mean that you don’t love. Doesn’t mean that you don’t suffer when it all unravels. I did—if not sleeping, eating, or going an hour without weeping are any measure. But I tried to pick my life up again. Having had enough of my briny sadness, I went blackberrying with a mother and her young son. Early evening before the mosquitoes, we carried plastic strawberry baskets and paper sacks. I picked my way through the thicket and underbrush and searched for the leggy canes. Blackberry thorns require precision. You have to choose. You have to sort (ripe, not ripe, too many brown drupelets). You have to move deliberately if you don’t want a thorn to teach you respect. I remember stooping, squatting, reaching over, and pushing my hand in and out of shadows, through scrims of weedy brush, and never giving a thought to snakes. This was Louisiana. There were snakes. But I didn’t think of them at the time. I wasn’t—for the first time in months—afraid. I only wanted to find the purple-black bumpiness called blackberry, to reenact the ancient theatre of scavenging and hunting, of searching. Briars, thorns, scratches, pricks, welts, and purple stains: I suffered all for the seedy sweetness. I remember later, after a bath and dinner, after washing and eating my plunder (what I hadn’t just popped into my mouth), I stretched out on the back-breaking reminder of a lost marriage, a salt-stained foam sofa, while night came on purple-black, humid, thorned by starlight and the canes of the Milky Way. I fell asleep.

Asparagus

Illinois, 1990s

![]()

I learned from a man whose son had died a year or maybe several years before—killed, I think, in a church-bus accident. He took me out, taught me where to look. We drove far from town. He stopped, finally, and we walked along the edge of farm rows, beside field fences, near railroad tracks. Wherever you find telephone lines, he said. Wherever birds shat their stolen seeds. We spent the afternoon going from site to site. He showed me his asparagus patch, so that I could learn to identify the ferns. They were easy to see once I knew their feathery foliage. He taught me how to bend the spine, just slightly, to find the breaking point, a precision that required practice and a kind of seeing touch. Take the slender, tender ones, but leave the tough, thicker stalks. He let me gather as much as I wanted, cautioning only that I leave some for the birds and other foragers, to reseed for the next season. We never spoke about his son. I wasn’t sure I had the story right. He hinted that there was something wrong with his wife, that she had not recovered. But he didn’t complain. Abandoned barns made good sites, he said, and old root cellars. Come back in the spring, and look.

I know spring mostly by its smell: earthy and clean. It’s also the season that requires patience, especially if you’re waiting to go asparagus hunting. But what woman goes into the countryside alone? What Black woman searches abandoned farmsteads or strolls along overgrown ditch banks to search for asparagus? The answer pressed against my skin. I could feel it, a knowing touch.

I gave way and called a girlfriend (Chicago South Side) and we went out together. I helped her see the ferny leaves and showed her how to bend slender stalks just so. Two Black women walking a rough seam of ground beside a railroad track, pickups passing by, puzzled faces turned in our direction.

Ephemera

Illinois, Late 1990s

![]()

In shoeboxes, in the jewelry armoire, in closets, in an upstairs crawl space, I keep old letters. My mother, my grandmother, my father also kept letters. You’ll want to look back some day, my mother says. There’s foraging in the reading of letters. Between Dear and Sincerely yours, I search for signs and memories and lore. Here the letter Anna kept for over thirty years. There, birthday cards, holiday greetings, and letters home. Cardboard reliquaries filled with yesterdays and bygones. Letters from friends, colleagues, lovers—now lost, moved on, forgotten. Old words. Old news. Old stories, yellowing. The acid of skin, air, and sunlight has brittled the paper and turned fading words into ghosts. In the winter, I pick through—old news: I guess you heard about my well cave in. . . .; cures: Get some sweet oil warm it and drop two drops in each ear do this for three times at night; recipes for cornbread dressing; and solace: there is nothing the Lord can’t do. I hear their voices again, the family left behind, faces that, after we went Up North, I never saw again.

Walnuts

Illinois, 2010s

![]()

At the Arboretum, immigrant families toss cudgels up into the walnut trees. Walnuts rattle and rain down in hard knots, along with leaves, twigs, and small limbs. The families stoop to gather walnuts. I cannot tell the words or language. But I understand the laughter and squeals.

Lillian boiled black walnuts slowly in a metal bucket to make dye for Webster’s shirts. That stain’ll get over everything, Anna warned. Be careful, if you do it. Never will come out. I remember how Anna spent hours cracking walnut shells and picking out the nutmeat to make a cake. Not worth the time it takes.

I gather a few from the ground, large enough to fill my palm, shells covered by black husks, to take home and crack with a hammer. It’s not as easy as you’d think. Walnuts are stubborn, and I was disappointed by the withered mummies I found inside. I’ll try again, one day. If not walnuts, then maybe pokeberries. I want to make ink, some indelible juice or stain, so I can write words that nothing will erase.

Janice N. Harrington writes poetry and children’s books. A native of Alabama, she teaches creative writing at the University of Illinois.

SIGN UP FOR THE DIGEST TO RECEIVE GRAVY IN YOUR INBOX.