Snow Falling on Collards In Minnesota, one newcomer offers another a taste of home.

by Rosalind Bentley

illustrations by Jade Johnson

![]()

Why in God’s name I moved from Florida to Minnesota, I will never fully understand.

I am deeply Southern, born and bred in Florida. But I’m not from tropical Florida—or, as we used to call it back in the day, “The Bottom”: palm trees, oranges, and bougainvillea. I’m from moss-draped, dirt-road, Big Bend Florida, more akin to Georgia and Alabama than Miami and Key West. I am okra and Gulf Coast oysters, peanuts and field peas, mullet and grits, and collard greens with threads of ham hock swirling in potlikker.

How did I land 1,115 miles north, trading sand for snow and sunburn for frostbite in the land of ten thousand lakes? The land of lutefisk and little smokies—those delightful mini hot dogs floating in barbecue sauce in a crockpot set on low. The land of “hotdish,” a catch-all name for the baked concoctions I grew up calling casseroles. (I soon learned that if the hotdish was topped with tater tots, I was all in.)

By the time I moved to the Twin Cities, in the late 1980s, the Great Migration was over. It began around 1910, and when it ended, around 1970, six million of us Black folks had left the South for points north, west and Midwest. Mechanization and pesticides—meant to control and manage crops—and racism—meant to control and manage Black folks who picked the crops—drove us away in search of better lives.

When I left home for Minnesota, the South was changing in critical ways. Black Southerners were gaining political power, if not economic equity, in larger cities, especially Atlanta. The stream was steady: Black people were returning to the South, back to our homeland, at least on these shores.

Yet I left. Joined a trickle of Southern migrants heading north. Many of us were graduates of HBCUs with degrees in business, engineering, journalism, or pharmacy. We were recruited for corporate jobs with companies that, a generation before mine, saw no need for Black folks in secretarial pools, let alone C-suites. The Twin Cities offered a better-paying newspaper job than the one I had in Tallahassee and a skyline of skyscrapers rather than live oaks. I planned to stay in Minnesota for five years, then move on to bigger and better things.

One Saturday morning ten years later, I walked down the concrete aisles of the Minneapolis Farmers Market, alone. It was fall, overcast and gray. The air promised snow and ice. There I was, wrapped in down, wandering past table after table of fresh-baked breads, bison jerky, bags of wild rice: everything a hardy Minnesotan would want in her pantry.

Though I could say the most Minnesotan of phrases with ease and appropriate accent by then (“Oooh, fur sure!” and “You betcha!”), in my heart, I was not a Minnesotan. I was a Black woman from the backcountry of north Florida. For me, the truest expression of that identity was on a plate.

But okra in Twin Cities grocery stores was always old and hard. Oysters had to be flown in. Other than the old VFW near Dale Street in St. Paul, where Black veterans went for bourbon and plates of succulent oxtails and gravy, there was really only one soul food restaurant in Minneapolis or St. Paul. I never could make my peace with their mac and cheese. Even so, I ate it. In a state where Black people were 2 percent of the state’s population, you counted yourself lucky if there was someplace other than your own kitchen serving stewed cabbage and cornbread.

Back then, in the 1990s, Hmong people comprised a similarly tiny sliver of Minnesota’s population. Pushed from China over a millennium, by the nineteenth century they had settled in the mountainous areas of Southeast Asia—many in the northern region of Laos, near that country’s border with Vietnam. As an ethnic minority, they faced discrimination.

In the early 1960s, the United States government believed that Communism threatened to march through Vietnam, across Southeast Asia, and eventually to India if it was not stopped before it overtook Laos.

The world focused on the Vietnam War. But in northern Laos, the CIA began a clandestine offensive known as “The Secret War.” It was dubbed “secret,” because US military troops weren’t deployed in Laos. Instead, the CIA trained and armed Hmong men and boys. Eventually, this civilian army of fathers, brothers, uncles, and sons—turned almost overnight into guerilla fighters and child soldiers—numbered more than 30,000.

The Secret War lasted a decade. Thousands of Hmong were killed in action or died in villages trying to survive. When it was over, and Communism was not vanquished, Hmong that fought with the U.S. military, along with their families, became the targets of an attempted genocide.

The United States government evacuated hundreds of Hmong veterans and their families. It left behind tens of thousands. Of those who remained, many attempted the treacherous journey across the Mekong River into Thailand, where they settled in refugee camps. There, in squalor and deprivation, Hmong refugees languished for years.

How did Minnesota figure into this? The state had a robust social-service and resettlement network, lead largely by the Lutheran Church. Minnesota received the second-largest number of Hmong refugees to the United States, after California. The first Hmong family arrived in Minnesota in 1975. Over the next twenty-five years, more than 40,000 people followed. In terms of physical distance, they traveled at least five times farther than I did. Yet—given the centuries of forced displacement, discrimination, and disproportionate poverty our peoples have faced—I must consider just how yawning the gap between our histories really is.

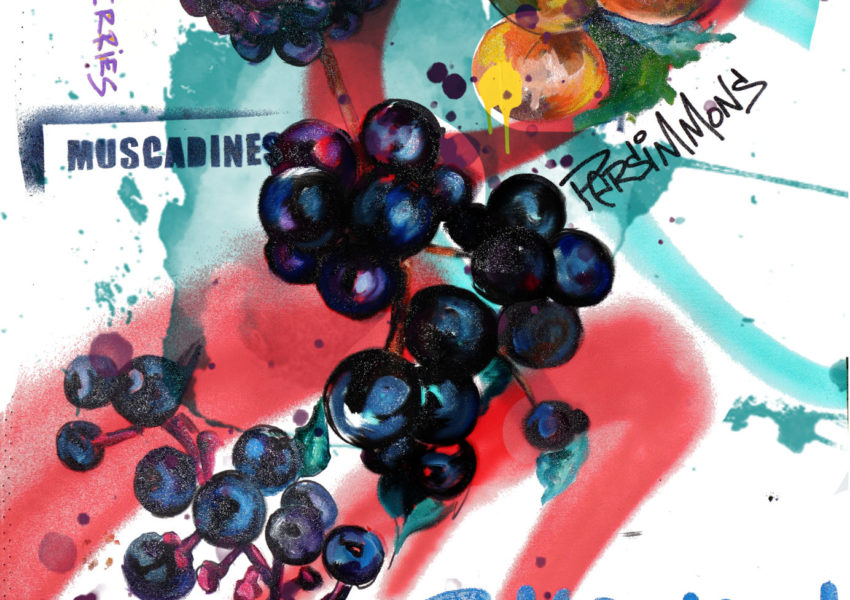

Northern Laos is mostly tropical, with a growing season that lasts nearly all year. The agricultural traditions of Hmong communities reach back thousands of years. Drawing on that knowledge and skill was one of the early ways they laid claim to their new home in the Upper Midwest. They adapted to the shorter growing season. Small community gardens sprang up, then exurban farms. Soon that bounty flooded the city’s farmers’ markets. In the decades that followed, Minnesota Hmong farmers would generate more than $250 million in annual sales of produce, based on some estimates. The impact on Minnesotans’ palates was significant, as well: Larb and purple sticky rice eventually became part of the state’s culinary canon.

Those early years on the tundra were hard, though. The language barrier was steep. Elders complained that the American-born generation neglected the old ways. And the war left scars. Those of the mind were hardest to heal. Winter lasted nearly nine months. When you’re far away from all you know, the cold can amplify your loneliness.

Maybe that’s why I was feeling so sorry for myself that chilly Saturday morning at the Minneapolis Farmers Market. Meandering from table to table, glancing at produce, I heard someone call out, “I have collards for yooou!”

I looked up, and an older Hmong gentleman smiled and beckoned me toward his table. I stared at him, thinking, Wait a minute. The one Black person you see, and you assume I want collard greens? For real? I mean, what kind of culinary racial profiling is this right here?

I had my eye-roll locked and was set to dramatically suck my teeth, but I stopped short. He was an elder, probably old enough to be my grandfather. His smile was genuine and disarming. It was as though he’d been saving this leafy prize of his labor and talent for someone who would appreciate it.

My face softened. I laughed at myself under my breath and walked over to his table. His collards were pretty. The leaves weren’t too big; the color was right. As my Aunt Mable taught me back home in Florida, collards are best picked after a cool night. They’re more tender that way.

I gathered bunches. The farmer held open a bag. I stuffed them in and left nary a leaf. As I paid, he thanked me and told me to come back. Clearly, I had not been his first Black customer.

A dear friend of mine does not believe that breaking bread together builds bridges. The act of sharing a meal may fill bellies, but it won’t solve problems, he insists. Perhaps he is correct. Perhaps it is a platitude we should retire. But on that day at the market, that gentleman and I were both trying to make our way in a place that was not ours. Collard greens, fresh with dew, helped us—if only for a few moments—walk that road together. In their own way, perhaps greens made us feel that we belonged; made us believe that in a place so white, so frigid, so foreign, we could be home.

Rosalind Bentley is Gravy’s deputy editor and the interim director of the MFA program in narrative nonfiction at the University of Georgia. This story is adapted from “Snow Falling on Collards: Finding Our Way Home,” a presentation given at La Cocina’s Voices From the Kitchen storytelling event in November 2019 in San Francisco.

SIGN UP FOR THE DIGEST TO RECEIVE GRAVY IN YOUR INBOX.