Of Chitlins and Care The women in my family blended customs with memories and served survival.

by Emily Hooper Lansana

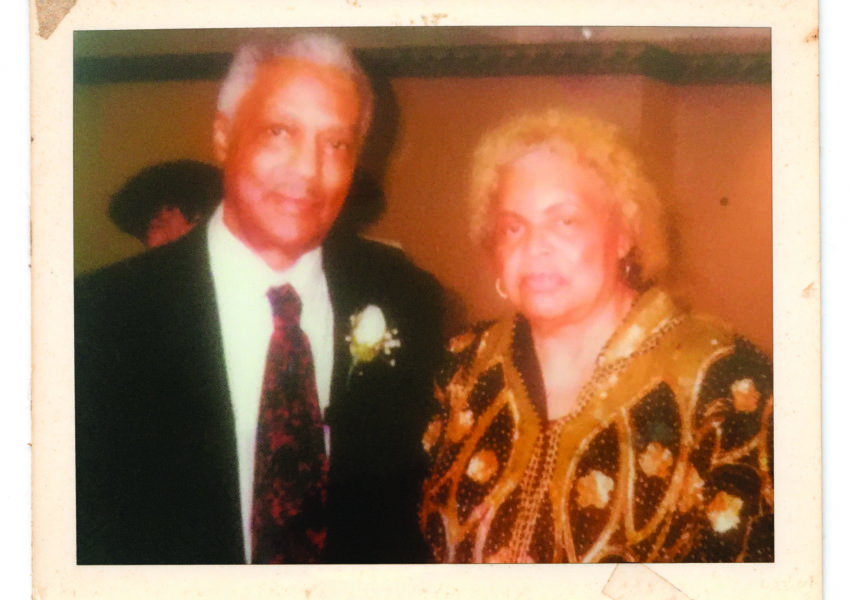

My earliest memory of enjoying the distinct taste of a particular food was when I was about three years old. It was early afternoon on Thanksgiving. My mother, my grandmother, and several great-aunts were in the kitchen finishing preparations for dinner.

I’d been playing in the living room when one of them handed me a saucer of soft, wavy food decorated with ketchup. I tasted this delicacy and finished the entire plate in moments. I asked for more. I finished a second plate. Chitlins were my first food love—until my older siblings convinced me otherwise. When I told my older brother and sister what I’d been eating, they explained in detail that the food I was falling in love with was called “chitlins.” They further counseled, “Chitlins are pig guts. You do not want to eat that.”

My great-aunts did not agree with my siblings. I don’t believe my elders participated in the complex task of cleaning and cooking chitlins solely because they loved the taste. The ritual of preparing chitlins reflected some of the journey of our people. It honored one of the ways in which we have learned to repurpose what has been discarded in order to sustain ourselves. These women blended customs with memories and served survival. I was a little girl who didn’t know what I was eating, but I did know that when they handed me that plate, I felt cared for.

When I was growing up, my elders served food drenched in wisdom and seasoned with courage.

At so many moments in my life, I have needed sustenance prepared with the kind of energy that emanated from that kitchen—food drenched in wisdom and seasoned with courage. My memories of soul food are as grounded in the foods themselves as they are in the care that surrounds the preparation, the serving, the eating, the gathering and the sharing. It’s not only what we ate, but how we ate and with whom we ate.

My family traveled north from Birmingham, Alabama, to Cleveland, Ohio, as part of the Great Migration. My great-aunt Ora was the first family member to move to Cleveland to pursue an environment with greater freedom and opportunity. When her father—my great-grandfather—Will Cogman, a tall, mahogany-brown man with a deeply chiseled face and wise eyes, heard about the quality of life for Black people in northern cities at that time, he followed. He wanted something more than the environment of racism, segregation, and limited education available to Black people in Birmingham. In their hometown, there were separate water fountains, they had to sit so high up in the theater that it was difficult to see the stage or screen, and the schools were separate and profoundly unequal. He found a job at a factory in Cleveland and saved until he was able to purchase a handsome, solid home and bring the whole family north. Generations of our family lived in that house on Olivet Avenue. We were proud to plant roots in a place where we could grow and dream without the daily battle of Southern segregation.

My mother often talks about how her grandfather nurtured and encouraged her. She says that he loved children and always wanted them to feel valued. Their family often hosted large gatherings. She remembers a table filled with foods like fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, turnip and collard greens, sweet potato casserole, pound cake, sweet potato pie, apple pie, and peach or blueberry cobbler.

My mother explains that at most other houses, the children had to wait until the adults had eaten. The kids then ate what was left over. However, in Will Cogman’s home, things followed a different order. He loved children. He called them his “chaps.” He said, “In my house, the chaps come first.” What an impact that must have had. Too few places in the world are structured to say, “Black children are loved and respected here. They are valued and nurtured. In this place, they come first.”

Too few places in the world are structured to say, “Black children are loved and respected here. They are valued and nurtured. In this place, they come first.”

When my great grandfather saved enough money to support the move and purchase a home, the family traveled north as part of the Great Migration. They carried their hope for more: for more opportunity, for financial and material blessings. They also brought the faith and the foods that had sustained them. My mother recalls that the meals were the same. From Oxmoor, Alabama; to Birmingham Alabama; to Cleveland, Ohio; my family carried that love of community, especially of children.

When my mother reflects on this move, she shares that the transition was not always easy. The school environment and community were very different in Cleveland than in Birmingham. She recalls that those family gatherings were an important part of feeding her body and spirit. When she was anxious, her grandfather said, “You are going to make it. You’re going to be somebody.” My great-grandfather’s work ethic and family values endure.

I never had the chance to meet my great-grandparents, but when I am standing in my mother’s kitchen and we are preparing her family menu from fried chicken and greens to pound cake and cobbler, for forty or fifty guests, I can feel the energy of my ancestors in the food, the music, and the stories. My mother is joyous when sitting in a house full of people around a bountiful table.

After college, I moved from Cleveland to Chicago and started a family. When my sons were little, I sometimes worried that they were missing something, because I didn’t always have time to cook the food that I’d been fed as a child. I was juggling a time-intensive job, navigating across the city between school, work, extracurricular activities, and doctors’ appointments. Sometimes I served them roasted chicken from the prepared foods section or microwave chicken nuggets rather than homemade chicken, macaroni and cheese, greens, and cornbread. I did not worry that they were missing nutrients; instead, I felt that the food that I had come to know as soul food, held the power to feed their spirits. These cultural dishes seemed intrinsic to being whole, strong Black people. Despite the myriad challenges of being a working mom to four Black boys in Chicago, I managed to feed them enough of what they needed to be grounded in their culture and hold a commitment to their people. I believe that my ancestors were consistently present, and that the ritual of sharing of foods from our history both honors their memories and calls them into the present.

These days in my kitchen, when I’m preparing a holiday meal with my sons—now young adults—cooking is a collaborative project. One focuses on fried chicken, another on macaroni and cheese, and another prepares sweet potato pie. One of them sets the table and greets friends. I set aside a plate for my ancestors on my great-aunt’s china. I thank them that we are well fed.

Emily Hooper Lansana is a community builder, storyteller, arts administrator, and educator. She serves as Senior Director of Community Arts for the Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago and teaches storytelling at venues from universities to community centers.

Photos courtesy of the author

SIGN UP FOR THE DIGEST TO RECEIVE GRAVY IN YOUR INBOX.