The Sanctum of a Bloom A pear pie marks womanhood across multiple generations.

By Rosalind Bentley

A couple of years ago, my mother and I were making our way through the Whole Foods produce section when she stopped at the pears. Green, yellow, red, and dusty brown, they stood single file in rows like choirs. Mama picked up a fruit the color of tender young sprouts and turned it, curvy and firm, in her hands.

“Umph. This one isn’t good,” she said.

It seemed fine to me. She loves pears, so I pulled a plastic bag for her to fill. Then she looked at the prices per pound.

“Three ninety-nine,” she said, her voice rising. “Who gon’ pay that for some pears?! That’s why folks can’t keep money, shopping in here.”

She put the fruit back in the bin. My mother was almost eighty years old then and though she’d been living frugally by training and necessity, the price was an affront to her. She grew up on her family’s farm in Jackson County, Florida. On their land, food flowed plentiful and free. From the corn kernels ground for grits, to the pigs and cows they slaughtered for bacon and stew, the family grew and raised just about everything they ate. They drank wine made from tangles of blackberries clustered near the woods. Their juices fermented in the log smokehouse in a tall clay pot most likely hand-thrown by one of our enslaved ancestors. The pot was available anytime someone wanted a swig of wine, enjoyed by itself or maybe after a helping of pear pie.

The pear tree was visible from my grandparents’ front porch, but to get to it you had to cross the fields and skirt the edge of the woods. In spring, the tree exploded with delicate white blossoms, each a promise of the bounty to come. By late summer, when the branches drooped and groaned with fruit, my grandmother would send my mother to the tree to harvest. Sometimes, Mama gathered a bushel for canning, but more often she picked a few pears for one of Grandma Willie’s pies. Juicy and lush, wrapped in delicate crusts, those pies were really more like cobbler.

My mother’s path reminds me of Janie’s, though no man like Tea Cake ever came along to sweeten a season of her life.

When I think of her walking toward that tree, I imagine my mother like Janie, the protagonist of Zora Neale Hurston’s master work, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Under the branches of a pear tree, Janie watches bees flit around a profusion of white blooms. She senses she’s on the cusp of womanhood. The pollinating bees suggest the ripeness of her own body, though she cannot name the change coursing through her flesh and mind.

In that moment, Janie is sixteen years old, unaware she’s about to be married off to a man old enough to be her father. She embarks on a life of trials that bruise and mark her. In time, she finds a real relationship with a younger man called Tea Cake. It’s an affirming but ill-fated love that leaves her with no regrets. Later, when the world begins to look past a middle-aged woman and toward girls on the cusp of bloom, Janie finds some peace.

My mother’s path reminds me of Janie’s, though no man like Tea Cake ever came along to sweeten a season of her life.

The pear tree Hurston describes with such longing and sensuality was likely the same type grown by my family. On the cover of old paperback editions of Their Eyes, the pear is rendered in a typical bell shape, like a Bartlett or a Bosc. Its skin is cast golden as an egg yolk. But the pear that grows best in north Florida, where Mama is from, and in central Florida, where Hurston was reared, is different. It’s an Asian variety, Pyrus pyrifolia, commonly called a “sand pear.” It can be round and stout like an apple. Its skin is mottled and rough, almost scaly. The fruit’s texture is gritty and its flesh dense. These are not beauties meant for display in the dining room fruit bowl.

Clearing weeds between the rows of peanuts on the farm, ironing shirts with Argo starch, or helping her father hold a pig for castration: These were ways my mother began to feel like she was commanding her young life. But watching her mother coax sweetness from those pears suggested a woman could conjure magic in the kitchen. In that room, my mother began her transition into womanhood.

Mama watched as her mother dropped big dollops of butter across the top of the pear chunks, dusted with a bit of nutmeg, before she crimped the top crust into place. The pies came out plump, their liquid like syrup.

Grandma Willie’s pie wasn’t the only sand-pear pie my mother knew. Aunt V, my grandmother’s sister-in-law, also made one. They called Aunt V’s a plate pie, because it didn’t ooze across the saucer when served. My mother tells me it was as firm and elegant as my grandmother’s version was saucy and voluptuous.

“You can go down there and mess up if you want to. You’ll be back here chopping cotton.”

Before she could master either of them, the realities of segregation pulled Mama away from her mother’s kitchen, the family farm, and the pear tree. She was a math wizard in school, and her family wanted her to go to an accredited high school rather than the Jackson County Training School for “coloreds.” So, at thirteen years old, they sent her to Tallahassee, just over seventy miles away, where there was an accredited high school for Negro children and a historically black college, Florida A&M University.

The sweetness of my mother’s life was about to dissipate. Just as Janie’s grandmother gave her advice before marrying her off, my grandmother gave my mother words to guide her: “‘You can go down there and mess up if you want to. You’ll be back here chopping cotton.’”

Translation: Don’t get pregnant.

If only my grandmother had warned Mama about the kind of man she should have looked for.

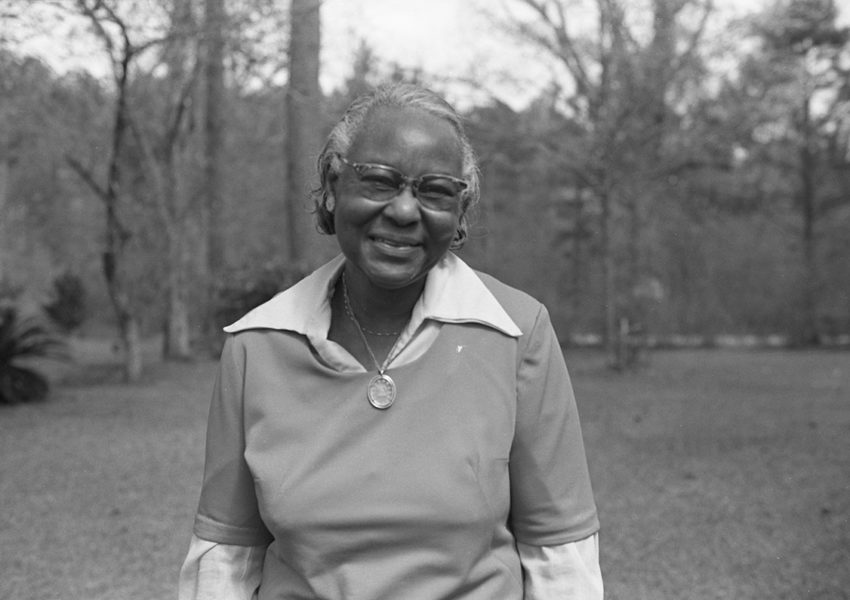

There aren’t many pictures of my mother from her early teen years. In a sepia one I’ve seen, she is lovely. There’s a light in her eyes. Her lips are soft and slightly plump. Her wavy hair is pressed into curls. Her skin tone is a soft amber.

That beauty attracted boys, but her mother’s admonition helped Mama keep them at a hand-holding distance, as did the older woman who boarded my mother in Tallahassee. Before she left Jackson County, my mother never had a boyfriend. A senior in high school, she started dating my father.

He was nice looking, smart, not particularly tall. His voice was a silken tenor. A sharp dresser, my father could be the life of a party. He also drank to excess.

He was the nephew of the woman with whom Mama lived. “Annie Hon,” as she was called, loved my mother and saw in her nephew an immaturity and a weakness that made him wrong for “Apple Pie,” her nickname for my mom. But my father was persistent. And my mother’s parents didn’t object, because my dad came from a decent family. Like Janie’s grandmother, they wanted her to be protected. Marriage was supposed to guarantee that.

Each offense taught my mother that womanhood could be a poor, hard place.

My parents wed during my mother’s junior year at Florida A&M, where she’d gotten a four-year scholarship. She was twenty years old. Matrimony meant she was a woman. In her mind, she would work hard, have four boys with a faithful husband who worked equally hard and whose love for her was abundant. That was the dream she’d nurtured since her days of going to the pear tree.

She did finish college, and she didn’t have a child until she had been married eight years. To say there was never any affection between my parents wouldn’t be accurate, but I never witnessed much of it. What she endured before and after my birth ended any white-blossomed fairytales.

The list of offenses sprouted like leaves and darkened the promise of her young life: The car that got repossessed as she, several months pregnant, prepared for work. The times the electric company cut off our lights because Daddy drank up the bill money. The nights he’d stagger in and pick fights with her as I listened in my room. The jobs he got and quickly lost because they were, in his mind, beneath him.

Each offense taught my mother that womanhood could be a poor, hard place. A place that makes you ask, “Lord, if it’s this hard with one child, what would I do with another one?” Though she dreamed of a brood, she never had another baby.

I don’t doubt that in the twilight of Jim Crow, being a black man who yearned for more was difficult if not emasculating for my father. But it was also crushing for a black woman so busy providing for her family on a meager secretary’s salary that she forgot what it was to be free, or worse, wondered if she’d ever known.

Yet there were moments of light—and they often happened in our tiny kitchen. There’s the memory of Mama zesting lemons against the old aluminum grater for a lemon meringue pie, her lips pursed, humming as she worked. By the time the egg whites were whipped into peaks and spread atop the pie, she’d be three verses into her third hymn. There was old-style banana pudding, bread pudding studded with raisins, and I think once, when I was in Girl Scouts, there was an attempt at caramel apples. On rare occasions, there’d be a sand-pear pie.

I’d watch her work, as she mimicked her mother’s steps. I was too young to see how the rhythm of the rolling pin across the dough and the notes forming in my mother’s throat helped her bear a bone-deep sadness.

By seventh grade, I’d developed my first real crush on a boy. I imagined we’d get married, a union the very opposite of my parents’. It would be perfect in every way. My body was transforming, as were my appetites.

Two events stand out as markers of my budding: One is the day I told my mother we’d be better off without my father and that she should divorce him. At first her face registered shock. As I kept talking she began to relax. On some level, I knew he loved me and I wanted to believe he’d once loved her. But it was too late. She was tired and so was I. It was difficult after their divorce, but with the help of family and my mother’s penny-pinching, we made it.

Each woman must find her own way forward, make her mistakes and her own magic.

The other is the day I decided to make a pear pie on my own. I think I was about thirteen, the same age my mom was when she left home. I’m pretty sure it was a Sunday after church. I followed her steps. Measure. Sift. Nutmeg. Plenty of sugar. Chips of butter. The kitchen was redolent as the pastry baked. When I pulled it from the oven, I was so proud. It hadn’t over-cooked, and I just knew it would dribble with honey-toned nectar when we lifted a slice from the pan.

When it cooled, we cut it. I was crestfallen. It wasn’t dripping. It was tight and clean. My first test, and I’d failed. I’m pretty sure I was about to cry, and my mother could tell.

“This is a plate pie! Like Aunt V’s,” she said.

I’d never seen Aunt V’s version, only my mother’s. But the way my mother relished each bite of it let me know it was okay to have done it my way. I didn’t realize it, but I was learning that each woman must find her own way forward, make her mistakes and her own magic.

This past christmas, my mother visited me and my partner in Atlanta. We’ve been together seventeen years. It was a love I didn’t expect, but recognized as genuine when it came along. My mother has accepted our relationship and treats my sweetheart like a daughter. For an eighty-two-year-old black woman from the rural South, who’s at church just about every time they open the doors, that is progress.

“Y’all seem happy together,” she said. Her smile told me she meant it.

Mama never remarried and she never found that chance at love like Janie or I did. She often said she didn’t want a new man in the house with a teenaged girl because not all men could be trusted. She was and remains a mama bear. But I also believe she didn’t want to risk her own heart breaking again.

I called her a couple of months before her Christmas trip. She sounded particularly upbeat. She’d been working in her garden all day and felt good. The house where she lives is the same one she’s lived in since before I was born, and she finally has it the way she has always wanted it. Her neighbors call her “The President,” because she’s the unofficial block captain who gets things done.

“You know, I feel like this is the best time of my life,” she said on the phone. “My health is pretty good, and I just feel like I’m free.”

Toward the end of her holiday visit, I told her I wanted to make a sand-pear pie. I hadn’t made one in decades and neither had she. At the Buford Highway Farmers Market we cruised bin after bin for a variety that would approximate a sand pear.

“Well, a Bartlett won’t work, so put that back,” she said as I reached for one. No to the Anjous and the Boscs. Then, in the organic section, we had a hit.

“Ummhmm, that’s it. That’s it,” she said as I pulled back the white netting cuddling each brown, scaly pear.

We got too many, and when the cashier rang them up at $26 for five-and-a-half pounds, Mama shrieked.

The night before I took her to the airport, I peeled half the pears and she sampled them for crispness.

“Ummhmm, the texture’s right. It’s good,” she said.

I sliced them as she always had and coated them with sugar and nutmeg. Then she rolled out the dough.

Rosalind Bentley is a senior staff writer at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Rosalind Bentley is a senior staff writer at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.