Hostesses of the Movement Everyday women fed a revolution

By Rosalind Bentley

When I was maybe eleven or twelve, we took a trip to visit my great-aunt Lucille Burton in Albany, Georgia. We called her Aunt Lucy. Before my mother and I left Tallahassee, Florida, where I grew up, I got the talk. I was supposed to be on my best behavior, make my bed without being asked, and scrub the bathtub with Comet each and every time I got out. These were my mother’s standard orders anytime we visited a relative. Especially at Aunt Lucy’s.

![]()

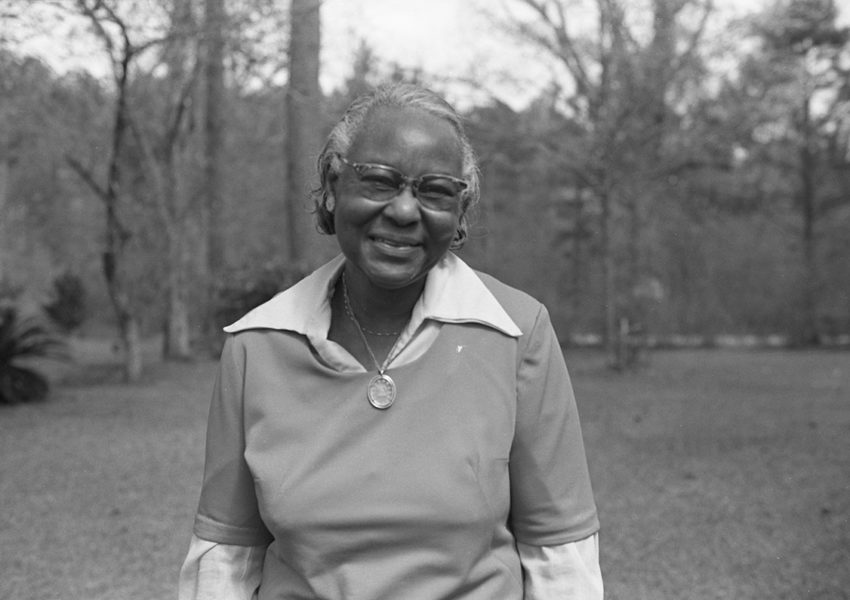

Aunt Lucy was the most sophisticated of my great-aunts. She had been a school teacher. Back then, that put her solidly in the black middle class. A black woman had few career opportunities and teaching in segregated schools was one of them. Aunt Lucy was built like a runway model, tall and slim. She was gorgeous. And so refined. I couldn’t get enough of her. Her little white bungalow was a palace to me.

A visit to Aunt Lucy’s meant crisp sheets on gleaming mahogany beds. It meant peeking through pristine lace curtains. It meant eating homemade lemon icebox cookies off of a china plate at the dining room table. Her starched linen tablecloth covered my knees.

This was in the 1970s. I was mostly worried about us getting to Aunt Lucy’s before Soul Train and wrestling came on. What I had not learned in my integrated middle school was that Albany had been an early battleground in the civil rights movement. Nobody ever said that Aunt Lucy’s house on West Lincoln Avenue had been a Freedom House. My favorite cousin, Brenda Webb, grew up in that house. She’s Aunt Lucy’s only child.

“Mama always made sure that her yards were in excellent order,” Brenda told me. “You had a front porch. You had an outdoor garage. And when you walked into the front, you walked into the living room, and on the right, was the front bedroom. Then you had a fireplace in the living room, and of course she had bought me a piano when I was five years old.”

You could say they were hostesses of the movement.

Now Brenda lives in Atlanta. She and my cousin, Clennon King, met here to talk about the contributions of women like Aunt Lucy to the civil rights movement.

“Where I always felt most comfortable was not in her living room or her dining room, or even in the hallway,” Clennon began.

“Where?” Brenda asked.

“It was in that kitchen,” Clennon said.

Clennon’s father, Chevene Bowers King, was an attorney for Martin Luther King, Jr. (Despite the shared surname, they weren’t related.) Around Albany, people called Chevene C.B. He was a founder of the Albany movement. He helped recruit Aunt Lucy and several other women who became stealth partners in the Albany campaign. You could say they were hostesses of the movement.

Compared to famous civil rights battlegrounds like Selma, Alabama, Albany holds an unsettled place in the history of the movement. Some called the early 1960s struggle a failure. The truth is more complicated than that.

It helps to understand the town’s past. For generations, agriculture made the seat of Dougherty County hum. Enslaved, and later, free blacks cultivated cotton, pecans, and peanuts. For decades, Albany and its surrounding county were predominantly African American.

“When it came to lynchings, they didn’t happen in Albany,” Clennon explained. “They didn’t happen in Dougherty County, because there were so many black people there. There was safety in numbers.”

After black men got the right to vote during Reconstruction, Albany sent black representatives to the state legislature. Jim Crow laws crushed their plans to help govern the land they built. By the 1920s, most black people who had been registered voters were purged from the rolls in Albany. If illegal poll taxes didn’t stop them from trying to vote, intimidation by whites in power did. With no vote, black people had no civic voice in a city where they were the majority.

Albany was a town of near-complete segregation: the schools, the neighborhoods, the hospital, the restaurants. If you were black, you couldn’t go into a white-owned store and try on a dress or hat. You couldn’t sit in the whites-only waiting room at the bus station.

“It wasn’t like there was an option for black folk to go check into the Holiday Inn,” Clennon said.

Aunt Lucy left our family farm in Jackson County, Florida, just before World War II. My great-grandparents wanted her to attend a historically black college in Albany, so they sent her up the Flint River to live with our cousins, the Kings. They ran The Little Wonder Café in Bobs Candy Company, purveyor of those iconic, twisted, red-and-white candy canes and peanut butter crackers. They owned a couple of grocery stores, a dress shop, and a good bit of real estate.

C.W. King, the family patriarch, helped found the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The voter registration drive in Albany was just beginning to gain traction in 1961. For the newly formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), it seemed the perfect opportunity. Black and some white college students worked to register African Americans to vote. When SNCC activists descended on Albany that year, they needed a place to meet. C.B. King’s brother, Slater King, who was vice president of the Albany movement, let them use an empty house he owned. The students also needed cheap places to eat—SNCC workers only made about ten dollars a week. A call went out across the community. Who could help feed these kids?

Rutha Mae Harris lives in the house her father built in the 1930s, just a few blocks away from Aunt Lucy’s. Her father was a minister; she was one of the original Freedom Singers, a quartet of young gospel vocalists who got their start at protest meetings in Albany. The Freedom Singers eventually traveled the country raising money for SNCC.

The Harris house is a pale-yellow bungalow with rust-colored shutters. It looks like a thick pat of butter dotted with cinnamon. Inside, family photos cover the walls. There are pictures of her with President Obama, and all kinds of certificates. It’s like a museum to Harris’ role in the movement.

“We housed a lot of workers here,” Ms. Harris said. “We slept them, we fed them. We would even sit out on that stoop out there. When we weren’t working, we just had fun.”

Before she hit the road with the Freedom Singers, Ms. Harris helped register people to vote.

“What made me realize I wasn’t free is when I did a voter registration drive. We did a citizenship school where we would teach people how to write, so that they could become registered voters. There was this man, ninety years old. He did not know how to write his name. When I taught him how to write his name, he shouted. I just hugged him.”

She knew how to set a welcome table.

Her mother, Katie B. Harris, stayed home to cook. Outside of a handful of black-owned restaurants, Albany’s diners and hotels were off limits to civil rights workers. Women like Ms. Harris’ mother stepped up. She knew how to set a welcome table. The house would be thick with the scent of candied yams and savory ham hocks in greens. When SNCC kids crowded the house at the end of the day, they emptied the serving bowls.

“Collard greens, cabbages, neck bones, fried chicken, cornbread, broccoli, potato salad,” Ms. Harris remembers. “Breakfast, it was bacon, grits, sausage, eggs, toast, milk, juice. Day in and day out until they were gone.”

Ms. Harris’ mother delighted in cooking for the SNCC workers. Her role wasn’t a hardship; it was an honor. “We were not a poor family,” Ms. Harris says. “My dad left us very well. My mother looked at it as her contribution because she knew that she was not gonna march. But she knew that her children would.”

Those marchers were arrested by the hundreds. The jail in Albany couldn’t hold them all. Neighboring counties locked up the overflow. Ms. Harris was jailed three times. By November 1961, many in black Albany were poking old Jim Crow in the eye. Students tried to integrate the bus and train terminals by taking seats in whites-only waiting rooms. Police Chief Laurie Pritchett promptly arrested them.

The Albany group asked Martin Luther King Jr. to be the voice of their fight. Legions followed. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the NAACP, Congress of Racial Equality, and more SNCC volunteers descended on Albany.

The influx meant more mouths to feed. More souls to sleep. Families across black Albany pitched in. The Terrells, the Georges, the Gaines, the Carnegies, the Nobles. Koinonia Farm, an integrated commune some thirty miles north, sent homegrown string beans, peaches, peas, and corn.

“It is a major part of activism,” says Maurice Hobson, a professor of African American history at Georgia State University. He grew up in Selma, Alabama, years after the Bloody Sunday march. “One of the ways, particularly within Southern vernacular culture, in which you show love and support is you feed people.”

Contributions of Albany women like Aunt Lucy, Aurelia Noble, Annette Jones, and Mardesque Shirley have been overlooked and underestimated. History has always focused on the men of the movement. Much of that history has been written by men. What women did in kitchens and gardens wasn’t as obvious as what happened on the streets and in courtrooms.

“Women really put gas in the tank to support the civil rights movement and they’re given very little credit behind this,” says Hobson. “Many of the domestics and black women cooks took off their jobs to make sure that the food was prepared for these protesters. We’re talking about the actual nuts and bolts of sustaining a movement based on food and rest.”

It was noble work. Hard work, for sure, preparing all those meals, always wondering if you were being watched by people who wanted to crush progress. Yet, when you talk to some of those women today, you get the sense even they devalue the role of cooking.

Juanita Abernathy is the widow of Dr. King’s chief partner and strategist, the Reverend Ralph David Abernathy. She prepared meals in Montgomery during the bus boycott, and then in Atlanta, where her family (and the Kings) eventually moved.

“Everybody wanted to say Juanita was the cook,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Wait a minute. Don’t classify me as the cook.’”

Dr. King knew their house well. “He would come by here almost every day, every night before he’d go home. Two or three nights a week. And whatever I had to eat, he’d eat,” said Mrs. Abernathy. She’s in her eighties now, and she still has the dark wooden dining set where they all ate. I wanted to know what was on those dinner plates. But she wanted me to be clear on one point.

“I had a bachelor’s degree in business and was teaching school. I’m not a home ec major. I learned to cook like every other woman, by the cookbooks. So, don’t relegate me to cooking.”

Mrs. Abernathy was by her husband’s side on many a march, and she was a strategist in her own right. She helped publicize the mass meetings in Montgomery that led to the integration of the city’s buses. She is a long-serving board member of Atlanta’s mass transit system, MARTA.

After some respectful prodding, and a little flattery on my part, she told me, “I make excellent rolls, but could not make biscuits. I still can’t make biscuits.” And I’ve eaten Mrs. Abernathy’s seafood gumbo. I can honestly say, she can burn.

Before the Albany movement was over, her husband and a few others would sketch their next assault on the system while sitting around Aunt Lucy’s dining room table.

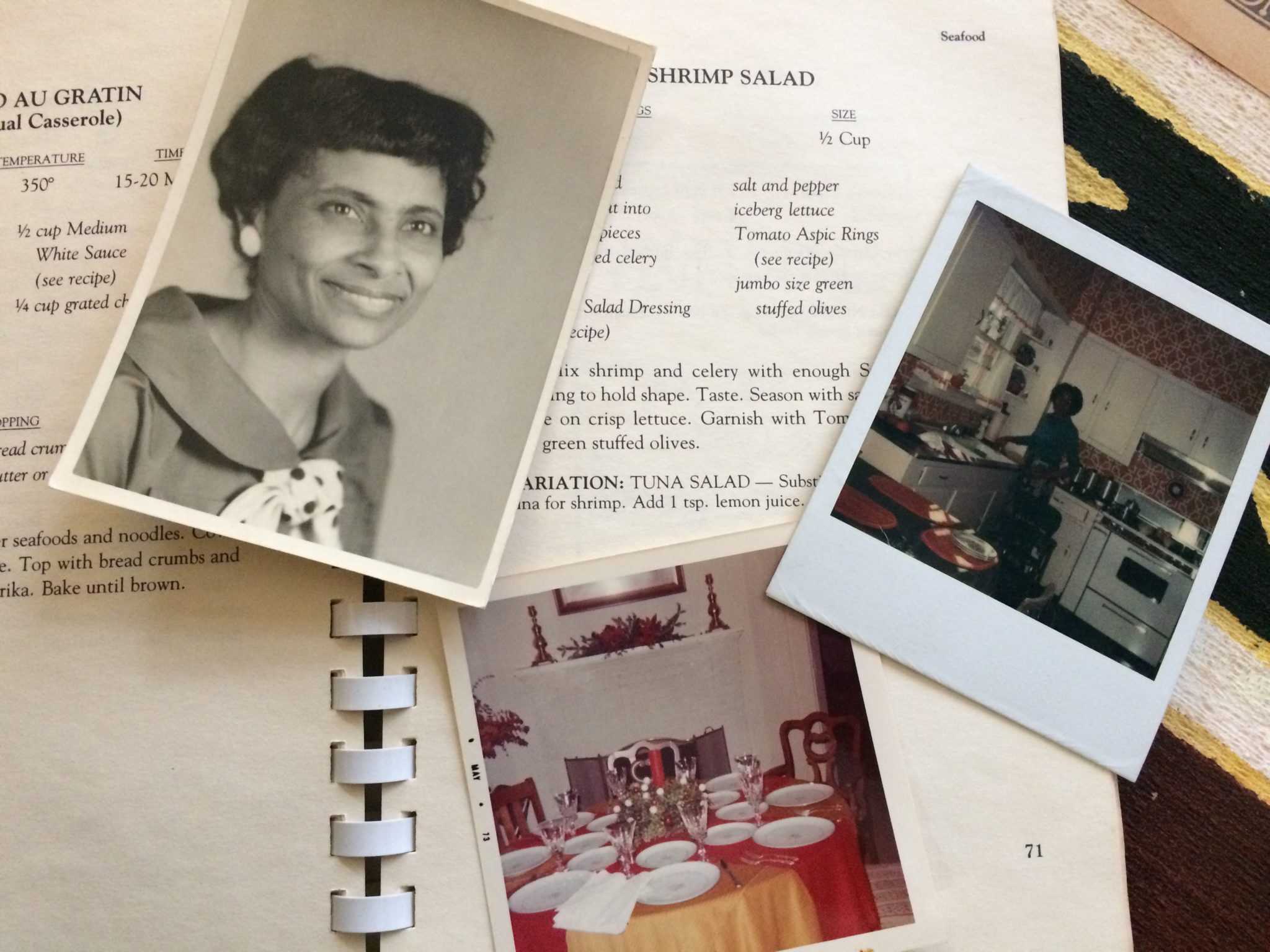

Unlike Mrs. Abernathy, Aunt Lucy had been a home economics major in college. Aunt Lucy entertained family and guests in a manner most high. Another cousin of mine remembers going to her house to eat a seven-course meal. Seven. On china. With stemware. Linen napkins across laps. She believed in putting her home ec degree to use. She also believed in progress, both in the law books and in the cookbooks.

Aunt Lucy had grown up on her family farm, eating off the land. As she got older and more citified, she embraced new recipes.

Among the middle class, the farm-to-table cooking she’d grown up with was giving way to convenience foods. Concoctions like seafood au gratin casserole with noodles or shrimp salad in tomato aspic rings garnished with stuffed olives. My cousin Brenda said Aunt Lucy would cook carrot soufflé. She never offered soufflé to me, but it fits. Making such dishes required skill—to take a humble vegetable and transform it into a delicate orange cloud. I have no doubt that soufflé rose in a ramekin with nary a chip nor hairline crack.

Brenda claims Aunt Lucy did cook turnip greens from time to time. When she got ready to bake her special coconut-pineapple Christmas cakes, she’d return to Jackson County, Florida, to get fresh butter and eggs. Her old-fashioned Southern hospitality, her assertion of dignity and a pursuit of worldliness through new dishes, are why C.B. King chose her as a hostess. The way she entertained declared that she was a black woman worthy of respect. Because when she walked out her front door, indignities would be out there waiting for her.

Dr. King, Rev. Abernathy, and hundreds of fellow protesters were arrested in Albany for leading a march without a permit in December 1961. Renowned lawyers arrived to help. They mounted challenges and secured injunctions. They bailed protesters out of jail.

Attorneys Donald Hollowell, Constance Baker Motley, and Vernon Jordan had just won a major case. They forced the University of Georgia to integrate, admitting its first black students, Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Hamilton Holmes. Fresh off that victory, Hollowell, Motley, and Jordan, then a NAACP field secretary, enlisted in Albany. Hollowell and Jordan often stayed at Aunt Lucy’s.

My aunt was measured in what she said, at least around me and my cousins. She would ask us what college we wanted to go to or tell us to stand up straight. But Jordan, who went on to head the National Urban League and become a close advisor to President Bill Clinton, saw a different side.

“She would talk to us and share thoughts and ideas with us. I always felt like I was at home,” Jordan told me.

Aunt Lucy gave advice to the lawyers?

“Well, I’m not sure that they were as much about advice as they were about information. Sharing what was going on and what was being thought about. That there was going to be a march at eight o’clock, another march at twelve o’clock, and another at four o’clock. And what the police chief was likely to do to people being arrested.”

Aunt Lucy? Miss Don’t-Laugh-So-Loud and Cross-Your-Legs-at-Your-Ankles Aunt Lucy?

“By virtue of staying at Lucille’s house, it made her a part of the movement because there was only one conversation,” Jordan said.

I don’t know if Aunt Lucy was ever afraid. During the peak years of the movement, Cousin Brenda was away at college in Baltimore. In the summer of 1962, she came back to Albany to visit friends. One afternoon, she walked across the porch, opened the front door, took a couple of steps, and froze.

“Sitting at the round dining room table was Martin Luther King,” Brenda said. “I was shocked.”

There’s a joke among people of my generation that everybody of Brenda’s generation has a Martin Luther King story. You know, I marched with Dr. King. I did this with Dr. King. I did that with Dr. King. Given what I’ve learned about my own family, maybe I shouldn’t be so flip.

“He was talking when I came in,” Brenda continued. “Martin Luther King was talking to them. I had never been that close to him before. And it was his voice and his eyes when he was talking that just amazed me. And I said, ‘Oh my goodness! If he told me to go and march with him, I would.’”

True to form, Aunt Lucy served him. Brenda thinks pork chops and chicken might have been on the table. She’s certain about the desserts. “They had pound cake and icebox cookies.”

Umph. Those lemon icebox cookies. A little zest. Some chopped Dougherty County pecans. Lots and lots of butter. Cousin Peggy, C.B. King’s daughter, remembers them well: “They would be rolled into these square-shaped tubes—almost logs. And she would keep them in the freezer. She could pull them out and they were very petite. Always ladylike.”

Federal District Court Judge Elbert Tuttle of Atlanta threw out the restraining order against the marches in late July 1962. Attorney Motley argued the case. (Four years later, Motley was named the first female African American federal judge in the nation.) The Albany movement as a formal entity was flagging. By 1963, Dr. King had moved on. Albany was still segregated.

“These are all unsung heroes, every one of them.”

But Jordan says the struggle there set the stage for Birmingham and Selma. “It was a very important round in the fight for civil rights. We learned the difference between saying, ‘we want it all right now,’ and taking two steps, because you couldn’t get it all. So there were a lot of lessons. Albany was instructive.”

C.B. continued to practice law in Albany. He defended the Americus Four, the Freedom Riders, and so many others. He kept the network of Freedom Houses in operation past 1962. Before she became a representative in the US House, Elizabeth Holtzman worked for C.B. in the summer of 1963. She was a Harvard Law student who’d found her way into the movement.

Rep. Holtzman stayed with two Albany families. She remembers how their warmth and grace made her hard work easier. “Every black family that took in civil rights workers took a risk. Their house could have been shot into, set on fire, bombed. All those things could have happened,” Holtzman says.

Some people lost their jobs for putting up so-called outside agitators. Some gave up precious space in homes that were already too tight. “These are all unsung heroes, every one of them,” Holtzman says. More recently, Albany has recognized some of those heroes.

Driving down West Broad Avenue in downtown Albany, you can’t miss this one big sand-colored building. It’s stately, elegant, and it commands the entire block. Across the front cornice is engraved in huge letters: C.B. King United States Courthouse. They dedicated the new building in his name in 2002. He died in 1988. C.B.’s oldest son, and his namesake, Chevene, Jr., has followed in his dad’s footsteps as a civil rights attorney.

There’s another monument, a five-minute drive away. It’s weathered, but still white. In another city, in another neighborhood, this house might have been fixed up by now, or honored on the National Register of Historic Places. Aunt Lucy’s old neighborhood has fallen on hard times. Brenda had to sell the house before Alzheimer’s disease took Aunt Lucy away from us. It was just too much to keep up. My aunt died in 2002.

My partner and I have a well-stocked bar at home in Atlanta. Our cocktail napkins are cloth. I’ll go ahead and say it: I’m a good cook. I can roast a chicken Edna Lewis style, fry and smother a pork chop Jackson County, Florida, style, and throw together a pasta for a weeknight dinner from what’s in our backyard garden. That garden is scented with Thai basil and heavy with white eggplant, Cherokee Purple tomatoes, and okra in late summer. But I don’t bake. Maybe it’s time to change that. Maybe I’ll start with Aunt Lucy’s lemon icebox cookies.

A couple of Christmases ago, we hosted a family brunch. I spent a week polishing silver. One of Cousin C.B.’s grandsons and his great-granddaughter were there, along with C.B.’s brother, Preston. White blossoms spilled from vases. I bought cathedral-height candles for the center of the table. When Brenda’s husband walked in, he took one look and said, “Lucille, Lucille, look at Lucille.”

I had arrived. And yet, to truly earn that praise, I must follow Aunt Lucy’s example and let our table be a place where resistance is not only welcomed, but nourished.

Rosalind Bentley is a writer at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. A version of this story, also titled “Hostesses of the Movement,” aired on Gravy podcast.