Searching for Soul Food in the once-Chocolate City

Does southern still have a

place at the DC table?

by W. Ralph Eubanks, with illustrations by Natalie Nelson

(Gravy, Winter 2016)

In spite of its location below the Mason-Dixon line, Washington, DC, does not feel especially Southern. I’ve always found Washington’s elusive regional identity part of its charm. By the time I left my native Mississippi and crossed the Potomac River to call DC home, it was still in the midst of its Chocolate City period, which began in the mid-1970s. At that time, the African American population rested around 70 percent. The nickname derived from the 1975 Parliament album of the same name that featured the Capitol, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial on its cover. I arrived five years after the record came out, but it was still a soundtrack for the city. Everyone I knew had a copy, whether on vinyl or cassette. Chocolate City also referenced DC’s status as the nation’s largest majority-black city (and with more African American elected officials than New York, Philadelphia, or Boston), a designation that we strutted proudly, echoing the funky beat of Bootsy Collins’ bass line.

![]()

For the first time in almost sixty years, Washington’s black population is now less than 50 percent. In a city whose foodways originate in Southern and African American sensibilities, I wondered what impact the population shift was having on the restaurant scene.

Washington attracted African Americans from the South—especially the Carolinas and Virginia—during the Great Migration of the twentieth century. Those migrants brought sweet potatoes, field peas, and cornbread to the kitchens and restaurants of the nation’s capital. During the latter half of the twentieth century, Southern cuisine shared a table in DC alongside French, Vietnamese, and Ethiopian. Today, Southern food is overshadowed by the creative fusion of foods, whether it is Korean tacos or shrimp fritters in chili sauce.

Among fellow Southern expatriates in the 1980s, our culinary adventures included catching new-wave and punk acts at the 9:30 Club’s old F Street location and eating late-night plates of lo mein in Chinatown to soak up all the beer we drank. We were too poor for the few power-dining establishments that existed at the time. The music of Talking Heads, Fugazi, X, and R.E.M. pushed us beyond our small-town upbringings. When we longed for something that tasted like home, we dug in at meat-and-threes: the long departed Whitlow’s or Reeves Restaurant and Bakery, with its sweet potato pies.

When we longed for something that tasted like home, we dug in at meat-and-threes.

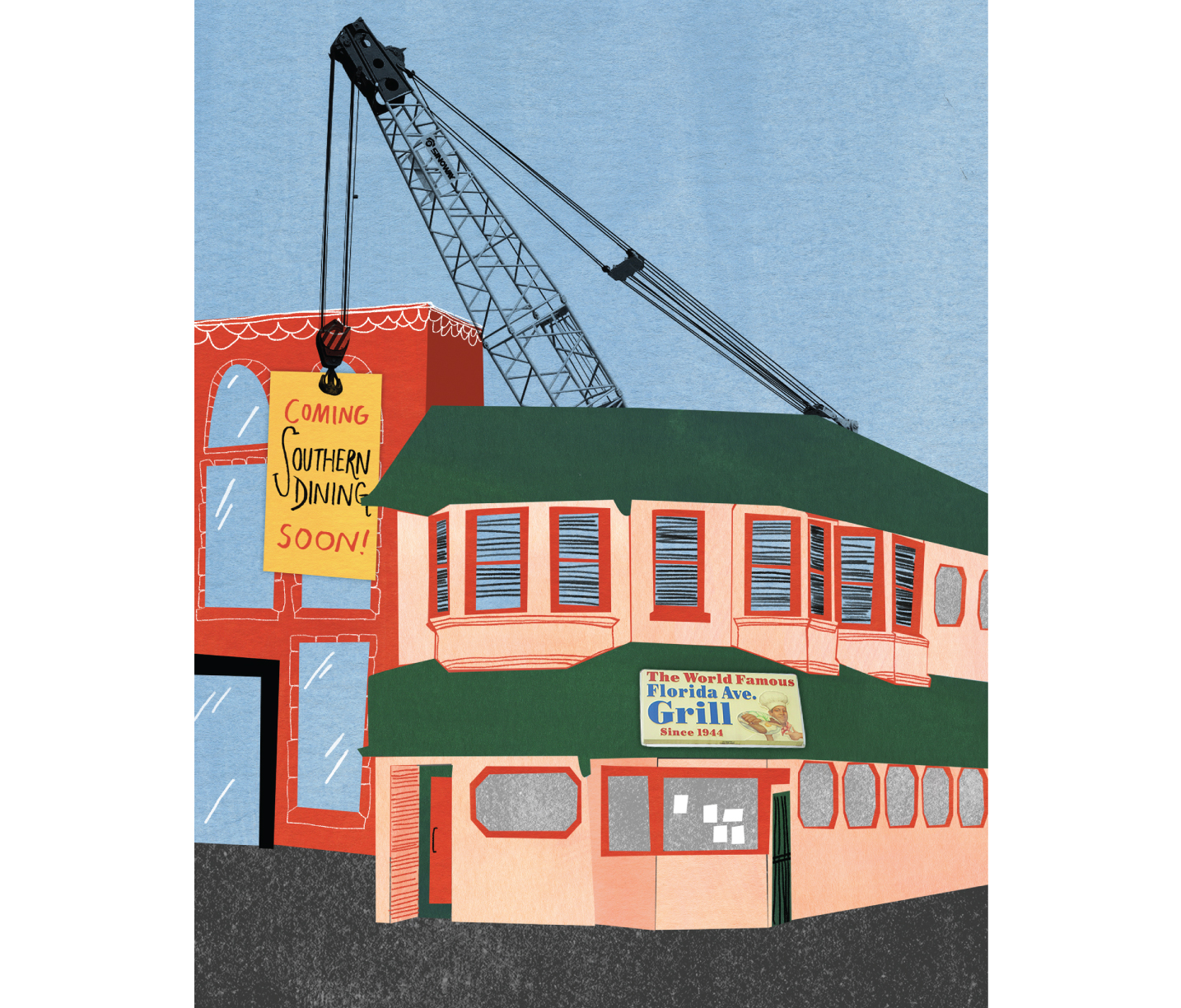

Today, one place remains from my early years in the city—the Florida Avenue Grill. It’s still located in the U Street corridor of DC near 14th St. NW, a neighborhood once known for the largest concentration of African American–owned businesses in the city and now the center of a burgeoning restaurant district. Whereas the Florida Avenue Grill built its reputation on dishes like smothered fried pork chops in onion gravy and baked chicken with cornbread dressing, these new restaurants reflect the city’s expanded palate. Today, even the Florida Avenue Grill has lightened up its menu offerings, influenced by an owner who previously operated vegetarian restaurants.

***

This past summer, I was back in DC after teaching as a visiting professor in my home state of Mississippi. In Jackson, I’d become devoted to the meatloaf and tomato gravy—with sides of rutabagas and fried okra—at Bully’s. Each time I ate there, I felt as if I had entered my grandmother’s kitchen, and I wondered if I could still find places like Bully’s in my adopted hometown. It didn’t take long to realize that what passes for Southern food has been adapted to please a younger, whiter, and more affluent clientele. These are diners who expect Gruyère in their macaroni and cheese and believe that grits are only worth eating if you serve them with shrimp.

In recent years, several Southern-influenced, white-tablecloth restaurants have opened. Crisp, a few blocks from my house in the Eckington-Bloomingdale neighborhood near Howard University, fries Nashville-style hot chicken. In the Shaw neighborhood, Southern Efficiency, a whiskey bar whose name evokes John Kennedy’s famous description of DC, pours mint juleps and old fashioneds. These restaurants and taverns have opened as the city’s population has grown more affluent, and they cater to those tastes. Bourbon drinks are a mainstay on cocktail menus. Dishes like pork and grits or pimento cheese and crackers pay homage to the down-home fare that were once DC staples, but they have been updated now that the city’s food culture stands on an international stage. A dish like pork and grits will have kimchi mixed in, a sure sign that this is not the old Chocolate City.

Although I have lived in DC for many years, I’m both a newcomer to the Eckington-Bloomingdale neighborhood and part of the forces of gentrification that are transforming the city. After our children went to college, my wife and I downsized from a house in upper Northwest DC. We were attracted to the restaurant scene that was beginning to rise up within walking distance of our new house. But now I wonder about the impact of my own evolving, eclectic taste in dining out. Am I knitting together the social fabric of the city, or tearing it apart?

Am I knitting together the social fabric of the city, or tearing it apart?

For the young people who populate the city, dining out is just as popular as catching a show at the 9:30 Club. Hip, upscale options now include Filipino restaurant Bad Saint or the progressive tasting menu at Minibar, and I appreciate those dining choices. Yet I still feel a lost connection with the DC of my youth. In trying to find a bridge between Mississippi and DC this summer, I learned that soul food has not disappeared, but has undertaken a migration of its own: across the river to Anacostia and Prince George’s County.

***

The Anacostia river, which separates the neighborhood of that name from the rest of DC, divides the city by race and class. Once you cross the Anacostia, there are few new construction sites and even fewer white faces. Strolling the neighborhood, I hear an amalgam of Virginia and North Carolina in the inflections of the words of people I encounter. I detect a palpable air of friendliness, too. Children ride bicycles with fishing poles and bait buckets attached to them, a scene that would fit in any riverside Southern city. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass purchased his Cedar Hill estate in the neighborhood in 1877. The view from Cedar Hill provides a panoramic view of the city. But since this is a predominately black neighborhood—which unfortunately, in the eyes of some, means unsafe—few tourists ever take in that vista.

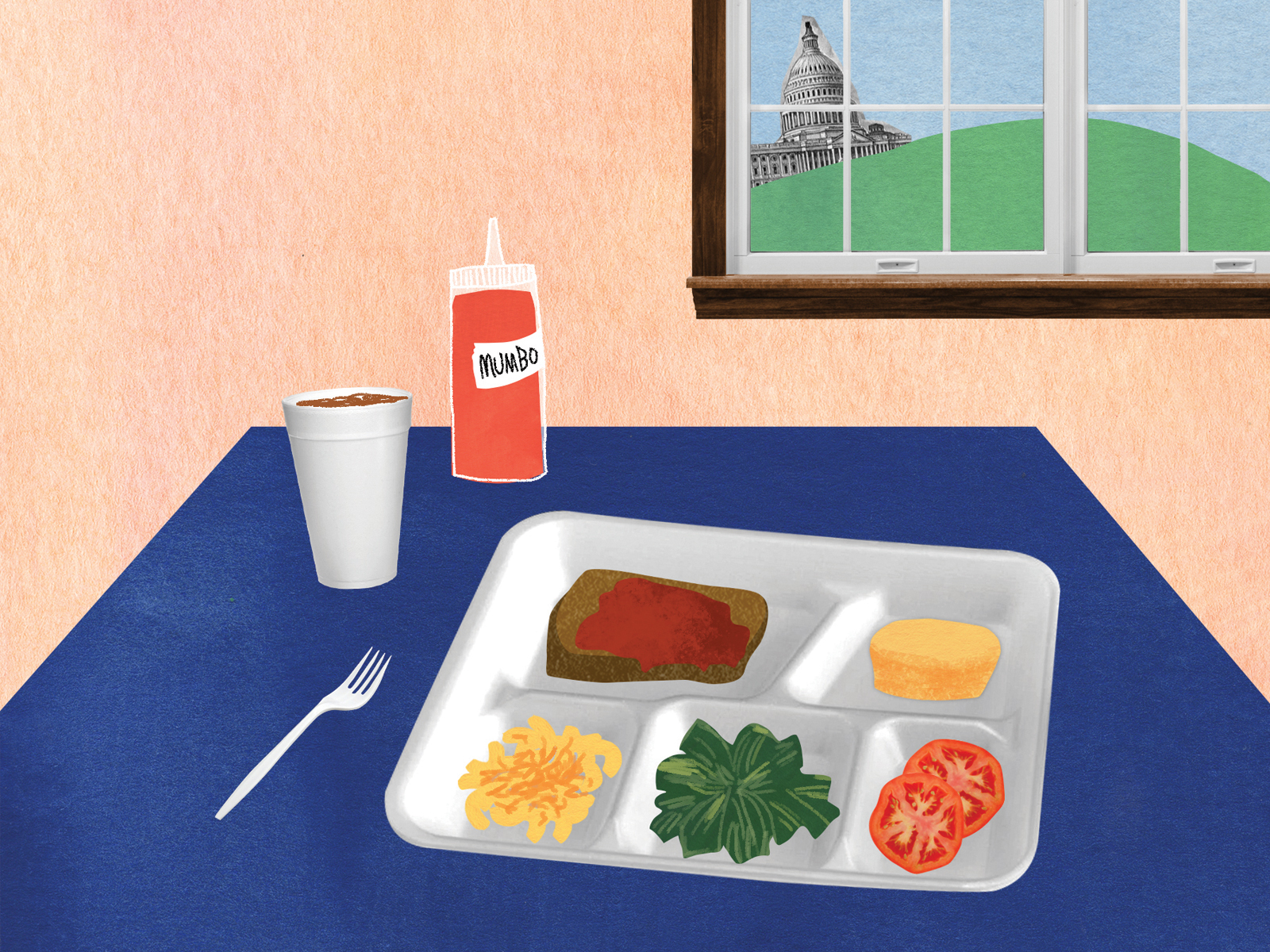

Crispy fried whiting, fried chicken, and greens dominate the menus of Anacostia’s carryout restaurants. Anacostia provided a place of refuge for me this summer, when a trip to Bully’s back in Mississippi was not an option. As I sat on a park bench overlooking the Potomac, eating meatloaf, collard greens, and macaroni and cheese out of a Styrofoam tray, I felt as if I was home in the Deep South as well as in DC. In this part of DC that includes the most impoverished neighborhoods in the city, the majority of eating establishments offer take-out only. There are fewer than ten restaurants with table service.

Like the rest of the city, gentrification has arrived in Anacostia, but change here has been spurred by young black professionals rather than whites and is moving at a slower pace. Here, few upscale restaurants serve that market. Uniontown was the neighborhood’s name when people began to settle there in 1854, and the food and drink at Uniontown Bar & Grill resembles what you might find at a pub on the other side of the Anacostia River. The menu offers fried catfish alongside the craft cocktails, a sign that this upscale place pays homage to Southern roots.

Just a few miles away, Prince George’s County is home to the most affluent African American enclave in the country. Washington, DC, is divided into eight electoral wards, and Prince George’s County is sometimes referred to as the “ninth ward,” since many of its residents once lived in DC. Henry’s Soul Café, once with several locations in DC—one on U Street and another in the heart of downtown that is soon to be cleared for redevelopment—moved there, and Keith and Son’s in Seat Pleasant is also a mainstay. Henry’s menu evokes the Carolinas, while Keith and Son’s menu echoes the foods of the Deep South. Soul food is alive and well, but largely on the other side of the Anacostia River and just across the District line in Maryland.

South of Anacostia, at the National Harbor development in Prince George’s County, you get a different picture. Among an assortment of fast-casual restaurants at this relatively new complex is Succotash, which offers dishes like collards, kimchi, and country ham from Korean American chef Edward Lee. Southern fusion has made its way here, across the District line, in a mixed-use development geared toward shoppers and tourists.

DC’s evolving food landscape toes a blurry line between economic displacement and gentrification. Changing demographics aside, I’d like to see DC restaurants pay homage to the former Chocolate City. Some of the new Southernish spots do that already by offering mumbo sauce, a sticky reddish-orange condiment native to DC. Mumbo sauce, which is sweet and tangy, is as ubiquitous in some parts of the city—including Anacostia—as comeback dressing is in Jackson, Mississippi. It is a staple in DC carryouts and is often served with french fries or fried chicken wings. A few upscale restaurants now serve mumbo sauce on sandwiches or with fries, much like comeback is found in a range of Jackson dining spots.

DC is changing rapidly. With the exception of the Anacostia neighborhood, there are few places in the city that show the old Southern and Chocolate City vibes—with the food to match. As the city grows, I fear the steady stream of newcomers will think DC was always filled with gleaming dining spots and upscale retail. On the spot of the old 9:30 Club on F Street NW sits a J. Crew and Anthropologie, making it hard to believe that the location was once part of the city’s alternative music and art scene. Sometimes change feels more like cultural erasure.

While I still love Southern food, like my fellow DC residents who live north of Anacostia, I often seek out innovation and a culinary shock of the new. I realize that I, too, have taken on the mindset that has come to dominate my city: My feet are in the South, but my head and palate, as Jesse Winchester once sang, are in the cool blue North.

Ralph Eubanks is the author of Ever is a Long Time and The House at the End of the Road. He has just completed his time as the Eudora Welty Visiting Scholar in Southern Studies at Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi.