POND FRESH Ed Scott and his catfish

Julian Rankin (Gravy, Summer 2016)

The neighbor jerked the wheel and pulled to the side of the dirt road to watch. He left his door open and scrambled onto the hood of his car to get a better look at the farmer, Ed Scott Jr., who was standing about a hundred yards off on a bluff of freshly exposed clay in what had recently been a soybean field. Scott was looking down at six feet of absent earth that stretched for acres. From a distance, it appeared to the neighbor as if Scott was staring into a crater left by a meteor. Even atop the hood of the car, the neighbor couldn’t see what was down there. He saw Scott wave his hands and whistle. He heard an engine roar and saw smoke billow. From the neighbor’s vantage point, it looked like the smoke came spewing directly from the earth. This optical illusion only heightened the magic. Scott is speaking to the ground, the neighbor chuckled to himself. And it’s doing as he says.

Ed Scott didn’t benefit from a safety net. If his crops failed, he failed. Born in 1922, he lived through the transition from farming by mule and man to the modern agricultural age of combines, laser-precise machinery, and integrated irrigation. Even with new technologies and massive United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) subsidies, well-equipped farmers like Scott earned frighteningly narrow profit margins. Most scraped by on grit and guts and trial-and-error lessons.

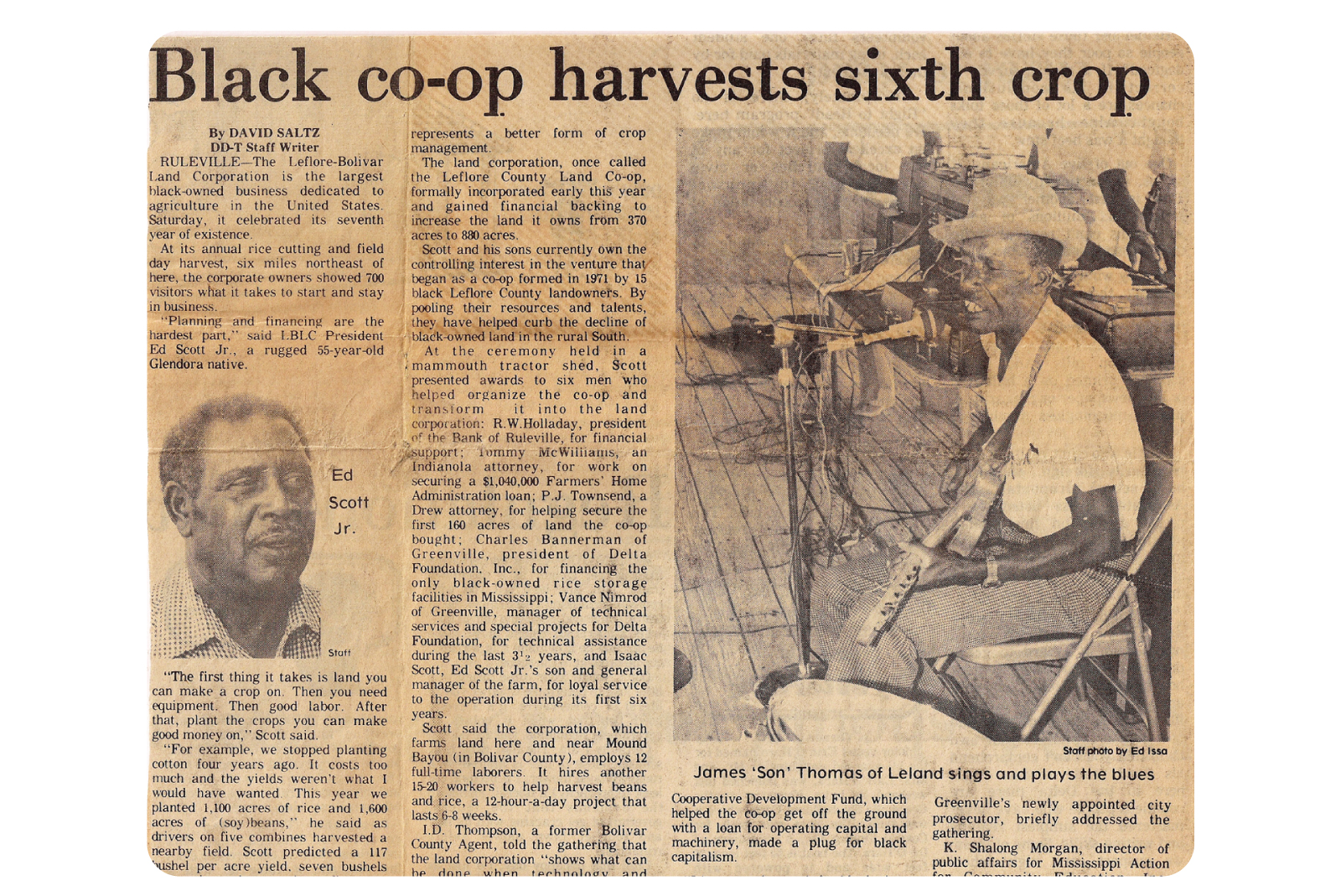

With these realities in mind, Ed Scott formed a cooperative in 1971 in the area of Leflore County, Mississippi, known as Brooks Farm. Black farmers shared equipment and pooled both their money and their labor. More than a dozen farmers joined the co-op, which was incorporated and organized as the Leflore County Area Cooperative (and later reorganized as the Leflore-Bolivar Land Corporation). The community coalesced around the co-op and around Scott’s assets and success. At the time, Scott was the only farmer with access to real capital. The hope was that smaller farmers could, through the co-op, acquire loans and government support.

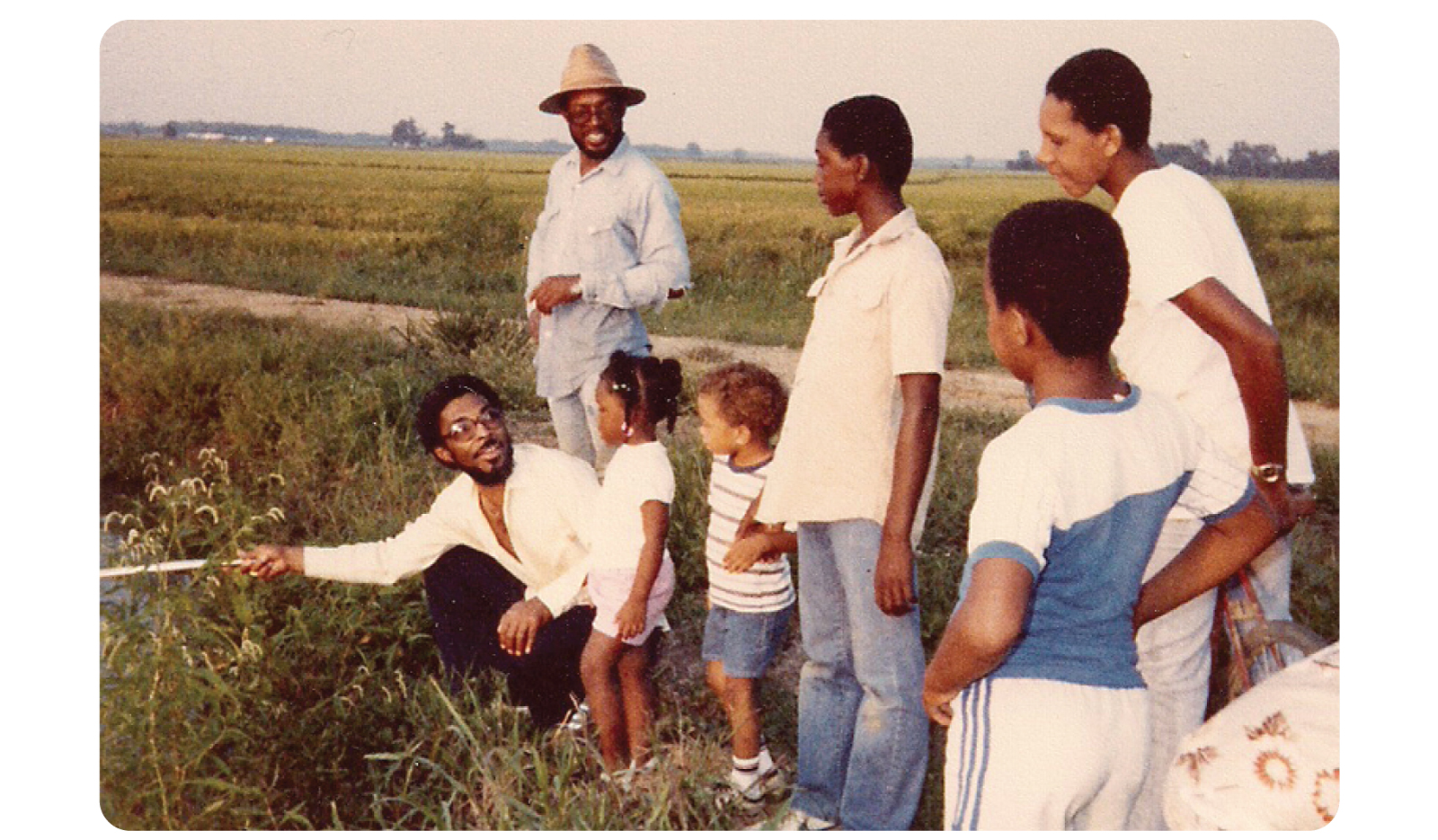

At the high water mark, Scott farmed close to 4,000 acres in two Delta counties, Leflore and Bolivar. Much of the land he owned. The rest he leased. He was a respected business leader and minority employer who supported a dozen families with jobs, including just about anyone from his extended familial web who wanted to work. Ed Scott was by far the most ambitious of his peers. Daniel Scott, Ed’s grandson, remembers his grandfather flying down the road on payday with a “big ol’ knot of money in his front pocket” to pay his workers.

It would have been tempting to note Ed Scott’s success in the late 1970s and early 1980s and say that the he had it made. He did not. Larger forces dwarfed Scott’s fiefdom. Scott’s relationship with the lords of agriculture was feudal, demanding obligation and subservience. Despite these constraints, Scott forged his own path of business success. His vision and execution exposed the fallacy of ordained white supremacy that had long dominated Southern agriculture.

Scott faced down the resentment and ill-will of peers and neighbors. He weathered institutional discrimination from the highest levels. In the absence of the panther, which had once ruled Delta swampland, a new threat emerged in the form of bank presidents and plantation owners and Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) agency supervisors who manipulated cash flow. It’s difficult to lay blame for this institutional misconduct at the feet of specific individuals. The people who tried to hold Scott back were pawns of the status quo. As Scott’s daughter Willena White puts it, “If it hadn’t been one man, it would have been another.”

FmHA, founded in 1946, extended credit to the people who were hardest off. It replaced an agency called the Farm Security Administration, which had done much the same during the Great Depression. In 1995, bureaucrats renamed FmHA the Farm Services Agency. Throughout these reorganizations and renamings, the mission has been the same: to provide financial leverage and aid to farmers in rural communities. As traditional agriculture grew more unpredictable and difficult to sustain in the latter half of the twentieth century, government programs subsidized heartland agriculture. Dollars funded disaster relief in times of flood or drought and bolstered operating reserves. The government provided life support for domestic agriculture, an important emblem of national vitality and self-determination, much as it continues to do for Amtrak, whose trains criss-cross this country day and night, passengers or no passengers. Farming is too central of an American ethic and ideal, too vital to the collective psyche to let falter.

Owing money to the government was, for farmers, as expected as wearing boots in the field. But the Scotts were unique for farmers of their size. They had not relied on government loans. Until 1978, the Scotts had secured cash directly from community banks, insurance companies, or economic development organizations like Mississippi Action for Community Education (MACE). Scott’s father, Edward Sr., had spent the years following the Depression making friends with bankers and bureaucrats. Scott Jr. valued the businesses relationships he developed at places like Bank of Ruleville. He never asked the federal government for money. Nobody had ever encouraged him to do so. He didn’t even think it was a viable option for the black farmer. In some ways, he was right.

Just as FmHA could extend you credit, they could also restructure your loan in times of hardship, or even write it off completely. The agency treated loans like Monopoly money. They approved, secured, and then subordinated most of the loans to local banks. The banks got their interest on the loan and the surety that came with a government cosign.

Huge sums from FmHA helped sow thousands of acres of farmland and supported countless workers. But in Southern communities with a legacy of segregation and prejudice, the money was not distributed equitably.

The Scotts first asked the government for money in January 1978. Vance Nimrod, a white man who worked with Delta Foundation, helped walk them through the process. Delta Foundation aimed to revitalize rural economies and build human capital in disenfranchised minority communities. On a Thursday morning, Ed Scott met Nimrod by his truck in the parking lot. They walked toward the FmHA office building in Greenwood. It was nondescript, four brick walls and a roof and little else. It could have housed a small-town dentist’s office.

A man greeted Scott and Nimrod inside the door, led them to a table, and left. Another man arrived and sat down across the table. This was Delbert Edwards, FmHA agency supervisor for Leflore County. Scott and Nimrod took turns talking, going over the numbers in the loan application. Scott had figured all of the expenses he’d need for a profitable year of rice and soybeans. Edwards made notes. When he spoke, he talked to Nimrod. In the end, the three men stood up and shook hands. Scott walked out of the office with every penny he’d asked for. That man didn’t even make us sign anything, Scott thought. The other farmers were right. It is easier to get your money from the government.

Scott reaped a good harvest in 1978 and returned to FmHA the next year. This time, he arrived to the office without Nimrod. Instead, his son Isaac Scott came along. Father and son sat down with Edwards at the very same table. Edwards pulled the file from the previous year. He opened it up and laid it before the men. But Edwards didn’t say anything right away. He sat still, waiting. A few long seconds passed as the men looked at each other. As Scott remembered it, Edwards finally asked them, “Where’s that other man?”

“What other man are you talking about?” said Scott.

“I’m talking about that white man. Where’s he?”

“He wasn’t part of us,” said Scott. “He was just with us to help us get our money.”

Edwards looked surprised. His pen slipped from his hand and fell to the floor. “He wasn’t with you,” Scott heard Edwards say softly. “Okay.”

Edwards picked his pen up from the floor. With it, he began marking through the figures on Scott’s loan application.

During the middle of the meeting, the FmHA office broke for lunch. Out in the parking lot, the Scotts got ready to drive away. As Scott climbed into the family Chevrolet—always a Chevy—Edwards prodded him. Scott recalled him saying, “Ed, that a new truck?”

“Yeah,” said Scott, leaning his head out of the window.

“Who told you to buy a new truck? Nobody told you to buy a new truck.”

“You don’t have to tell me to buy a new truck,” Scott said, pulling away. “I know how to spend my money.”

The truck was akin to the suits that Ed Scott Sr. had worn in the fields a generation before: a signifier of business acumen and respectability that defied hierarchies of master and worker.

FmHA officers were not micromanagers by rule. In general, a farmer had the leeway to purchase equipment or feed or irrigation pipes or batteries or work gloves or groceries as he saw fit. If the farmer was white, it seemed, his financial judgment could be trusted. “Does your wife need a new car this year?” Isaac Scott remembers overhearing an FmHA loan officer ask a farmer. “Let’s put a little money in for that.”

The truck was akin to the suits that Ed Scott Sr. had worn in the fields a generation before: a signifier of business acumen and respectability that defied hierarchies of master and worker. Scott could have stuck with a late model Chevy. But he didn’t succumb to the expectations of others. Instead, he bought new Chevrolets. He rode high on top-of-the-line tractors. He spoke truth to power.

The Scott family rose to prominence during a time of change, when demand and price fluctuations for staple row crops like cotton, rice, and soybeans destabilized agriculture. During the mid-twentieth century, farmers profited from a tested range of crops and consistent government-backed subsidies. The primary source of instability was the weather. As U.S. farmers entered world markets, the situation changed.

As distribution of Southern crops globalized and grew more volatile, farmer demographics shifted. Between 1969 and 1980, the number of individual farms decreased from nearly 1.74 million to about one million. At the same time, the size of the average farm increased. Small, independent farmers, white and black, whose presence atop their tractors on the Delta roadside had been ubiquitous, fell away. In their place came conglomerated, corporate agribusiness. This movement left one group buried in the loam: black farmers. Their ranks had already been declining. Modern restructuring exacerbated the slide. In 1950, more than half a million black farmers worked land in the South. By 1978, that number had dwindled to about fifty thousand.

As distribution of Southern crops globalized and grew more volatile, farmer demographics shifted. Between 1969 and 1980, the number of individual farms decreased from nearly 1.74 million to about one million. At the same time, the size of the average farm increased. Small, independent farmers, white and black, whose presence atop their tractors on the Delta roadside had been ubiquitous, fell away. In their place came conglomerated, corporate agribusiness. This movement left one group buried in the loam: black farmers. Their ranks had already been declining. Modern restructuring exacerbated the slide. In 1950, more than half a million black farmers worked land in the South. By 1978, that number had dwindled to about fifty thousand.

During that same thirty-year period, emerging markets whipsawed from boom to bust. Profits for old standards like wheat and rice and soybeans oscillated wildly. Crop variability, a term that describes this fluctuation, doubled for wheat in the years from 1964 to 1980. Shifts were even more dramatic for soybeans. Agricultural economists predicted more of the same in the years to come. Because world markets were beyond control of domestic growers, small farmers suffered the most.

The Russian embargo of 1980 exacerbated the uncertainty. In response to the communist superpower’s intervention in Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter cut off all sales of U.S. grain to the USSR, the largest importer of U.S. corn and wheat. The short-lived embargo did little to cripple the USSR, but the American farmer, already walloped by inflation, took the hit as Soviet export markets dried up.

How could leaders in Southern agriculture insulate themselves from these variables to create more sustainable and predictable outcomes? For the answer, farmers in the Mississippi Delta looked to a classic Southern folk ingredient with big business potential: catfish.

By the 1970s, Mississippi surpassed all other states in catfish farming and production.

Along with other working-class foods like chitlins and cracklins, catfish had previously been relegated to the muddy bottom of the American food chain. Long before the fish was a commodity, Southerners hooked cats on cane poles or bought them from enterprising fisherman. Commercial catfish farming was born in Arkansas. Farmers raised fish in the Delta region of that state by the late 1950s. Mississippi followed with its first documented commercial catfish pond in 1965. By the 1970s, Mississippi surpassed all other states in catfish farming and production. In the 1980s, the industry doubled in size. Mississippi took the leadership role in American catfish and would be responsible in the years to come for roughly eighty percent of the country’s catfish production. The alluvial landscape of the Delta proved ideal for catfish. The deep soil deposits of the Delta drain poorly. That soil supported and retained giant ponds. New technologies and industry organization spurred growth. In the early years of commercial catfish farming, farmers marketed their own products, mostly locally. With the formation of catfish trade groups in the state and the emergence of large processing cooperatives like Delta Pride of Indianola, farmers took advantage of new research, resources, and marketing plans. The Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce helped form the most influential of these trade groups. The Catfish Farmers of America and the Catfish Farmers of Mississippi promised cohesion and organization to the industry. Under their leadership, catfish became a bankable commodity.

These trade groups, along with other agricultural agencies and researchers, introduced new methods for raising, feeding, and processing the fish. Consistency was the ultimate goal. With improvements and resources, farmers could provide a product that appealed to middle-class consumers. Taste testers graded the fish prior to processing to control against unpleasant flavors.

In the catfish industry, these various substandard tastes are known as “off-flavor,” a more innocuous term than the “muddy” designation. Not inherent to the fish itself, off-flavor catfish are the result of environmental factors, including diet, pond contamination, weather, and—most commonly—absorption of bacteria through the skin and gills. For Southern catfish farmers, a bacteria produced by pond algae was the primary offender. The fish absorbed these bacteria into their fatty flesh, resulting in a slightly medicinal taste. Ever-conscious of their brand, the modern catfish industry put in safeguards to silo these off-flavor fish from the market until the pond environment improved.

In the catfish industry, these various substandard tastes are known as “off-flavor,” a more innocuous term than the “muddy” designation. Not inherent to the fish itself, off-flavor catfish are the result of environmental factors, including diet, pond contamination, weather, and—most commonly—absorption of bacteria through the skin and gills. For Southern catfish farmers, a bacteria produced by pond algae was the primary offender. The fish absorbed these bacteria into their fatty flesh, resulting in a slightly medicinal taste. Ever-conscious of their brand, the modern catfish industry put in safeguards to silo these off-flavor fish from the market until the pond environment improved.

Long-held consumer perceptions proved more difficult to change. With a consistent product in place, industry groups launched informational campaigns and touted the delicacy to all who would listen. NBC Today Show weatherman Willard Scott sampled the fish on air in 1985, declaring, “If I go down for anything in history, I would like to be known as the person who convinced the American people that catfish is one of the finest eating fishes in the world.”

Black farmers like Ed Scott were largely forgotten in this agricultural recalibration, left to figure out their own alternatives to traditional row crops. Delbert Edwards never expected Scott to build his own catfish ponds. He assumed Scott’s row cropping operation would falter in the wake of declining markets. While the white farmers talked about how to tap into available government resources, Scott didn’t benefit from information about best practices and marketing strategies. But he saw the future clearly, and he heard the message this way: Find resources where you can, become a catfish farmer, dig your own ponds, harvest your own fish, and make your own markets—or quit farming.

“I got the sense that FmHA was preaching catfish to a group of white farmers and Ed Scott was on the outside of the room listening in,” says attorney Phil Fraas, who would become one of Scott’s staunchest allies in the eventual Pigford v. Glickman class-action discrimination case against USDA, starting in 1997. “He wasn’t included on the conversation, but he listened well and did it on his own. That, I think, is what really ruffled Delbert Edwards’s feathers. The idea that those conversations weren’t meant for you, that strategy is not meant for you because you’re the black farmer. You’re supposed to be the smaller operation and the basic one-tractor-do-your-soybeans-and-that’s-it setup.”

“I watched Mr. Ed dig those ponds,” said one of Scott’s neighbors. “I just woke up one day and they were out there digging catfish ponds. It was absolutely fascinating. And still to this day, it was unbeknownst to me how they did it. All that land, it used to be just rice. And it turned into a fish pond.”

Delbert Edwards showed up when Scott and his sons had almost finished digging the last of eight twenty-acre ponds. He wasn’t there on a planned visit. He didn’t drive over to lend engineering advice or to congratulate Scott on the progress. Edwards had gotten wind that a black farmer was digging holes in the ground and calling them fish ponds, and he wanted to see it for himself. He shut his truck door and looked out over the 160 acres of transformed rice fields. Edwards began walking toward the ponds. Scott met him halfway. Now that he had the ponds, maybe he and Edwards could get along after all, he thought. Now that he could make FmHA some money. The two men came face to face. Scott greeted Edwards—who, as Scott recalled, only had one thing to tell him. “Don’t think I’m giving you any damn money for that dirt you’re moving.”

Delbert Edwards showed up when Scott and his sons had almost finished digging the last of eight twenty-acre ponds. He wasn’t there on a planned visit. He didn’t drive over to lend engineering advice or to congratulate Scott on the progress. Edwards had gotten wind that a black farmer was digging holes in the ground and calling them fish ponds, and he wanted to see it for himself. He shut his truck door and looked out over the 160 acres of transformed rice fields. Edwards began walking toward the ponds. Scott met him halfway. Now that he had the ponds, maybe he and Edwards could get along after all, he thought. Now that he could make FmHA some money. The two men came face to face. Scott greeted Edwards—who, as Scott recalled, only had one thing to tell him. “Don’t think I’m giving you any damn money for that dirt you’re moving.”

Scott finished his ponds in 1981. He applied for another loan from the local FmHA office for 1982. He needed fish, and he needed feed. Edwards was less than enthusiastic. When he and Scott met to run the numbers for a proposed operating loan, Edwards said little. He made notes while Scott spoke. At one point, Scott recalled, Edwards scribbled the figure “50 cents,” presumably indicative of his evaluation of the loan request. Scott didn’t get his money that day.

Scott knew that if he couldn’t obtain funding, the ponds would remain empty basins. With no satisfactory response from the local office, he made a trip to the state FmHA office in Jackson. Papers in hand, he pleaded for help to get his money moving. The state arm of FmHA reviewed Scott’s situation and instructed Delbert Edwards to fund the farm. Scott did receive an infusion of cash. But the amount was insufficient to stock the twenty-acre ponds he dug. He received a third of the approximately $450,000 required to capitalize an eight-pond operation. Of the ponds he dug, no more than four were ever full.

The Scotts stood on the edge of the pond in the late summer of 1981. Sealed plastic bags full of fingerling channel catfish floated on the surface of the water. Inside the bags, the little fish wriggled in their confined puddles, becoming acclimated. Scott and his sons waited and watched. In ten minutes, the temperature difference between the water in the bags and the ponds stabilized. Bending down, Scott broke the seal on one of the bags and let the waters mix. The baby catfish, incubated in a climate-controlled hatchery, entered the frontier of the murky pond water. They swam cautiously from their enclosure into the wider pond, investigating their new surroundings.

Here’s how Ed Scott farmed catfish in the early 1980s: Scout the land. Dig the ponds and drill the wells. Stock the waters with young fingerling catfish, bought from a hatchery in the nearby town of Drew. Buy as much feed as possible and launch the soybean-rice-wheat-protein pellets across the pond. Grow the fish to maturity. Harvest the fish. Get them processed, hopefully at the big new processing plant a few counties south. Sell them far and wide.

He’d done an impressive job of stocking his ponds with the money from FmHA. Scott spent the rest of it on feed, and he needed more. When he went back for more money, Edwards refused. Scott said that Edwards told him to “let the fish die.”

When he saw a roadblock, instead of looking for a shortcut, Scott built a new highway. And he barreled down the double-yellow line in a black Chevy truck at breakneck speed.

Catfish begin to reach maturity at around eighteen months. As he managed his first crop of fish, Scott steadily worked to find a processor. The Delta catfish processing apparatus had developed parallel to the growing industry. Delta Pride was the largest and most technologically advanced plant in the area. The Indianola-based company helped realize the modern industry in 1981. Structured as a farmer-owned cooperative, the company built relationships with farmer-stockholders who provided a steady supply of catfish, which Delta Pride processed, marketed, and distributed across the region.

To gain entrée, Scott gave the man his family called “Lawyer Townsend” instructions to purchase Delta Pride stock on his behalf. But when P.J. Townsend attempted to make the transaction for Ed Scott, Delta Pride wouldn’t sell it to him. Townsend relayed the conversation to Scott. Here’s what Scott heard: Lawyer Townsend wasn’t able to buy stock “according to the color of your skin.”

Few, if any, farmers vertically integrated their operations. For a catfish farm to succeed, a typical farmer relied on a number of different companies, services, and funders. If Scott couldn’t get enough funding from the government, he couldn’t buy any more fingerlings or feed. Without a plant to process his fish, he’d be shut out of the marketplace. Scott had planned for this likelihood. He resolved to skin his own fish if it came down to it. Ed Scott didn’t get into catfish to wage political war; he wanted to earn a living. When he saw a roadblock, instead of looking for a shortcut, Scott built a new highway. And he barreled down the double-yellow line in a black Chevy truck at breakneck speed.

Few, if any, farmers vertically integrated their operations. For a catfish farm to succeed, a typical farmer relied on a number of different companies, services, and funders. If Scott couldn’t get enough funding from the government, he couldn’t buy any more fingerlings or feed. Without a plant to process his fish, he’d be shut out of the marketplace. Scott had planned for this likelihood. He resolved to skin his own fish if it came down to it. Ed Scott didn’t get into catfish to wage political war; he wanted to earn a living. When he saw a roadblock, instead of looking for a shortcut, Scott built a new highway. And he barreled down the double-yellow line in a black Chevy truck at breakneck speed.

Though he never could buy stock in Delta Pride, the company became a resource for Scott. Proud of its state-of-the-art production line, Delta Pride regularly welcomed visitors and potential investors. Scott asked Lawyer Townsend to set up a visit. Townsend’s secretary made arrangements, telling a Delta Pride secretary that she was sending over “two prominent businessmen who would like a guided tour.”

On a clear Delta weekday, Scott and his son Isaac drove the hour over to Indianola. They were quiet and reflective. “Don’t tell them we’re here to see what they’re doing,” Isaac said as they drew close. The complex was imposing and stark against the distant treeline and brushy growth of the surrounding farmland. It was also physically large in a part of the state where many homes are small, and where big buildings mean big power.

“Don’t tell them you’re going to try to process your own fish,” Isaac warned his father. “Because they aren’t going to tell you a thing after that.”

Scott held his ground “If he asks, I’m going to say exactly what I’m down here for: to see what they’re doing that I can’t do myself.”

Both men, participants in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, were well-versed in the proactive tactic of the sit-in.

When they arrived, Scott and Isaac sat down in the waiting room. A lady told them to make themselves comfortable and wait. They waited for the better part of forty-five minutes. Both men, participants in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, were well-versed in the proactive tactic of the sit-in. Finally, a man named Larry came out from the back to say that he would be with them in a few more minutes.

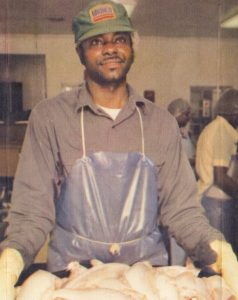

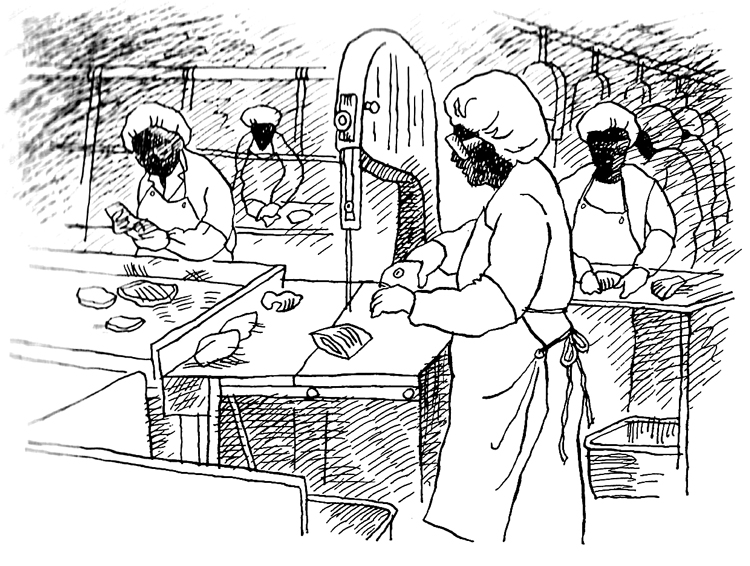

Seeing the inner workings of Delta Pride, glimpsing the perpetual motion of man and machine, was like lifting the veil on Wonka’s factory: the hum of refrigerators, the suck of eviscerators, the RPM drone of headsaws, the zoop zoop zoop of a hundred blades cutting, cutting, cutting. Plant workers sorted the fish by size and weight, some destined to be packaged filets, others steaks, some sealed and frozen whole. As the fish came down the line, workers deftly severed the body from the head. The next crew snatched the bodies, ripped open the stomachs, and sucked out the entrails. Moving up the line, the skinners took charge. The fish would then be boxed and labeled and stacked on palettes by a different set of gloved and calloused hands in a separate department of the factory. This fast-twitch ballet happened almost wordlessly at Delta Pride. It was cold. Precise. Black men and women, who accounted for almost all of the manual labor positions, repeated their calibrated tasks in tandem with the machines.

On the way through the plant, Larry made conversation. He told Scott and Isaac what each person was doing and why. Father and son listened. After a while, Larry asked, “So do y’all have a catfish farm?”

“Yeah,” said Scott.

“You got any stock in the plant?”

“Nope,” said Scott.

Larry stopped walking. They were near the loading dock now, in front of the thick plastic bannered curtain that separated the skinning side from the packing side. “You got anything lined up with live haulers, then?”

“Nope.”

“Well then, what the hell you going to do with your fish, eat ’em?!”

“Something like that,” said Scott.

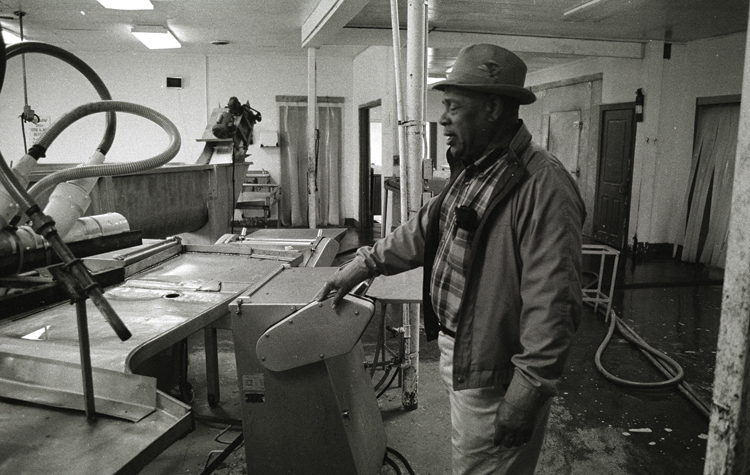

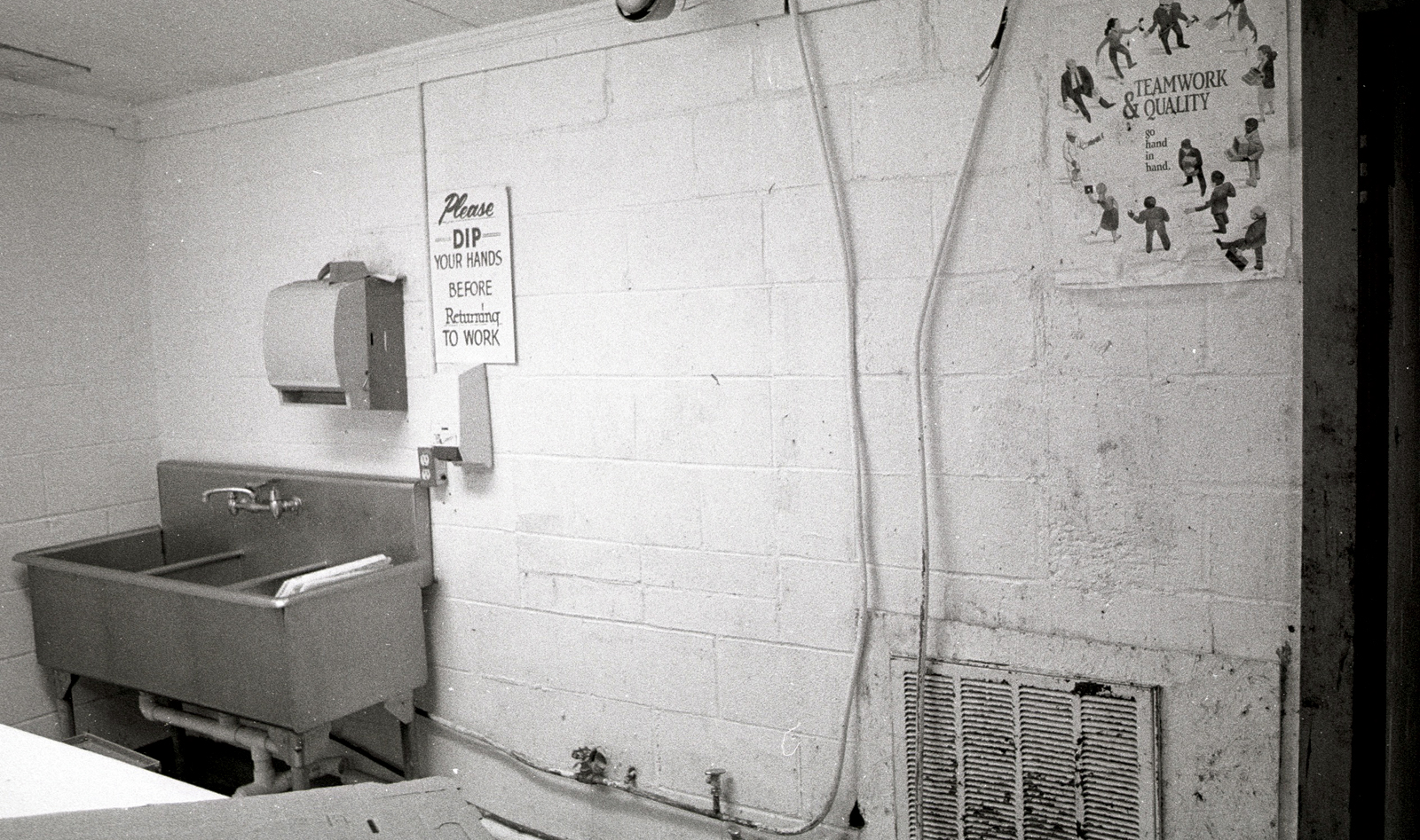

Scott financed the processing plant out of his own pocket, bit by bit. Frank Brown, a self-taught carpenter from nearby Drew, laid concrete on one side of the plant. Scott paid him half. Brown laid down concrete on the other side. Scott paid him the other half. Every little while, he’d call Brown and ask for something new to be constructed. Bit by bit, the plant emerged. What had been a dirt-floor tractor shed on wooden posts became an insulated, self-contained catfish processing operation, plopped in the middle of nowhere.

As construction continued at Scott’s Fresh Catfish, later renamed Pond Fresh Catfish, Scott reached out to the Mississippi State University Extension Service’s Food and Fiber Center and told a professor there that he was installing a one-line catfish plant. Scott asked him if they had any literature on it. The man said no, but that he’d get something from Auburn University. “Something” turned out to be a four-page pamphlet about what building materials to use inside the plant. No wood, no fiberglass, all stainless steel. That was all Scott needed to know.

“I called that doctor back and told him I received the information,” says Scott. “‘And when I get done,’ I said to him, ‘I want you to come inspect it. When I open the doors, I’m going to be able to sell to anybody.’ And sure enough, I did.”

Ed Scott became an unwelcome catfish dorsal jabbed in the hand of FmHA, who now wanted him out. With the knowledge he gleaned from that brief glimpse at the lines of Delta Pride, Scott propelled himself forward.

Ed Scott was self-educated. He studied the processes of others. Folk methods and efficiencies worked their way into his philosophies. Before the plant was complete and automated, he had taught workers to deep-skin the catfish, then a little-used technique. Daniel Scott reckons that his grandfather picked up the practice from watching a worker meticulously skin discarded runt fish to take home, a skill that worker might have gotten from his aunt who got it from her mother, and so on.

“Scraping the black stuff off the bellies” is how Ed Scott described the skinning process to a layperson. Workers removed the grime and film from the fish with a bristled brush. The industry now calls a similar cut “delacata.” It’s considered the best cut of the fish, a sort of catfish tenderloin.

Scott’s Fresh Catfish opened on a cold, clear February day in 1983. The air pulsed with excitement. Family, friends, and newly hired plant workers milled in the gravel drive between the plant and the Scotts’ home. The one-line plant was smaller than any in the Delta as far as Scott knew, but it was still substantial, larger than the farm house where he lived. The builder had expanded the footprint of the former tractor shed, constructing a cinder block–walled main killing floor that connected with offices and loading docks. Wood-plank siding, laid vertically and painted a striking red, covered the exterior of the administrative wing. The color popped against the adjacent cinder-block wall, painted white. The finishing touch, hung up just hours before, was a hand-lettered wood panel that said SCOTT’S FRESH CATFISH.

Scott himself paced, waiting for the right moment to throw open the doors. Jim Buck Ross, Commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce, smiled big and shook hands. His warmth defied the temperature outdoors. When Scott felt it was time, he opened his arms to invite attendees closer. As the group tightened, Scott spoke in a booming voice. He spoke to the audience but also past them, as if he were addressing a crowd of thousands. Scott talked of being “the first black-owned plant processing farm-raised catfish in the nation.” Applause and hollering erupted when he invited all to “come on in and have a look.”

Scott himself paced, waiting for the right moment to throw open the doors. Jim Buck Ross, Commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce, smiled big and shook hands. His warmth defied the temperature outdoors. When Scott felt it was time, he opened his arms to invite attendees closer. As the group tightened, Scott spoke in a booming voice. He spoke to the audience but also past them, as if he were addressing a crowd of thousands. Scott talked of being “the first black-owned plant processing farm-raised catfish in the nation.” Applause and hollering erupted when he invited all to “come on in and have a look.”

Before the plant opened, and for a good bit after, workers on the Scott’s Fresh line skinned fish by hand. They hooked the slit throat of the fish on a nail, grip the flesh with hand-skinners, and shuck it like a wet pair of pants. On opening day, the workers held a speed contest. One bout decided who could skin the fastest. Another determined who could filet the most whole fish. Someone with a video camera taped the sprint. Eva Brooks, who would become the driving force inside the plant, out-skinned everybody. Her cousin Darren won the filet contest. There were no prizes, save the pride that African American workers found in African American success.

After the commemoration, attendees broke apart and continued to talk in small groups. Some went back inside to look closer. Others walked around the side of the plant to the concrete vats that would hold the wriggling fish from the ponds. One worker pulled out a boom box from her car. When Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” came on the radio, someone cranked the knob as loud as it would go. A group of women workers, dressed in black Lee jeans, picked up the beat and juked across the dirt. The workers pulled Scott and Isaac onto the makeshift dance floor. The men let loose, too. The two farmers flailed and stomped to the music. A worker described their motions as “wigging and wopping.”

The women at the plant called themselves “The Dependables.” They lived nearby and worked any and all shifts, in snow and storm, amid mud and guts.

The women at the plant called themselves “The Dependables.” Along with Eva Brooks, Lillie Watson, Essie Watson, and Elnora Mullins completed the core crew. They would work long hours in the coming years to keep the plant thriving. They lived nearby and worked any and all shifts, in snow and storm, amid mud and guts. They were tough. Scott’s grandson Daniel, a teenager when the plant opened, calls them “mannish ladies.” They did everything that the men could do. And more. “We throwed them thirty pound boxes of fish just like a man,” says Eva Brooks. “Those men taking their time, we chucked it like it was nothing.”

Scott learned by example and led by it. Many of his workers had been desperate for gainful employment for months or years. Scott gave them jobs, and he also offered them purpose. He trusted and inspired them.

Back in the 1960s, Ed Scott had provided food from his farm to hungry Freedom Riders. He had marched at Selma, too. But he made his real contributions to black enfranchisement by tinkering within the established system, not seeking to wholly dismantle it. Scott fused free-market principles, protestant work ethic, and American exceptionalism with a spirit of contrarian ambition. He used the law and the loan and the letterhead as an example for those around him. He treated his workers with dignity. That respect paid dividends.

Back in the 1960s, Ed Scott had provided food from his farm to hungry Freedom Riders. He had marched at Selma, too. But he made his real contributions to black enfranchisement by tinkering within the established system, not seeking to wholly dismantle it.

When the Scotts were away, the Dependables ran the day-to-day operations. When it came time to lead, they led. On pay days, they felt proud.

Civil rights leader Ella Baker reportedly said to young members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the mid-1960s as they left for Mississippi to register black Deltans to vote, “Go and tell the people on the plantations that they don’t have to wait on the elite. They don’t have to wait on Roy Wilkins. They don’t have to wait on James Farmer. They have people among them who are capable of being leaders.” At Scott’s Fresh Catfish, a new generation of leaders emerged.

In addition to working the line, the Dependables cared for their children, running home between shifts to fix dinner and help with homework and draw baths, coming right back to pick up where they left off. Essie Watson went into labor at the skinning table. Her water broke mid-fish. She calmly drove herself home, took a bath, and drove to the hospital, where she gave birth to boy. In a few more tellings, that story will have become a bit of Delta lore, too—like the story of Ed Scott. She will have given birth to her son right there on the line, on the same table where her coworkers were pulling guts and chopping heads, never breaking her rhythm.

Watch “On Flavor,” a profile of Ed Scott.

Ed Scott Jr., winner of the 2001 Ruth Fertel Keeper of the Flame Award from the SFA, died in October 2015. His beloved wife, Edna Scott, passed in May 2016. Late in his life, a federal court awarded Mr. Scott damages and declared that his row crop and catfish farming operation had been subjected to discriminatory lending practices by the Farmers’ Home Administration. The Scott family plans to honor the legacy of Ed and Edna Scott with the Delta Farmers Museum and Cultural Learning Center, to be constructed on the site of the tractor shed that Mr. Scott converted into a catfish processing plant.

Julian Rankin is a native of Mississippi and North Carolina. His writing and photography explore Southern identity and place.

Illustrations by Ellen Joy Sasaki. Historical photographs of Scott’s Fresh Catfish courtesy of Willena White and Julian Rankin.