NORTHWARD BOUND Detroit’s evolving food system has deep Southern roots

by Devita Davison (Gravy, Spring 2017)

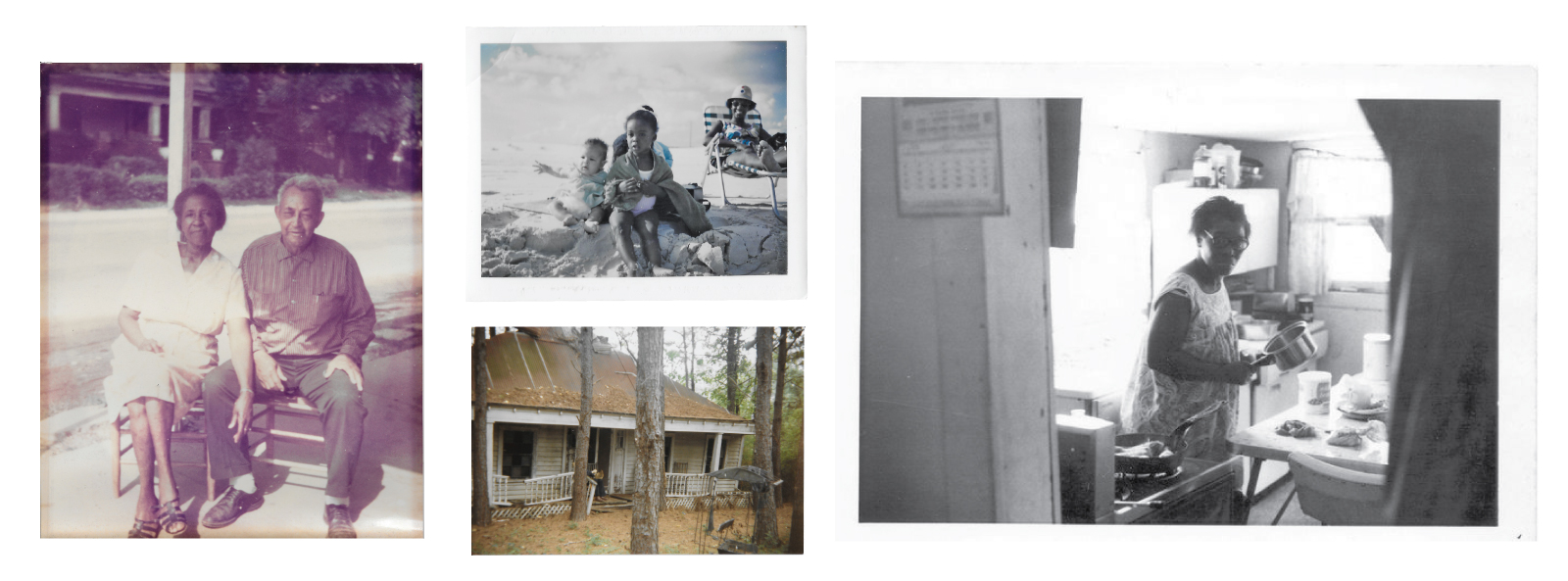

I was born to a family of extraordinary cooks, obsessively preoccupied with food. My maternal great-grandparents owned a general store in Selma, Alabama. My grandparents and parents grew up on farmland their families had worked for generations. They cooked with garden produce, chickens and hogs they raised, and hen house eggs they collected. Growing food, preparing it, and eating it: Through those daily rituals, our family forged bonds and created memories. But then, like so many other African Americans, my family quit the South.

Between 1910 and 1970, more than six million African Americans moved to cities like Detroit from states like Alabama, where they had lived and worked as tenants and sharecroppers. Down South, home was often a dire cabin or clapboard shotgun. Houses lacked glass windows or screens. Bathrooms were often outdoor privies. Water came from wells, springs, and creeks. Detroit promised escape. “I am in the darkness of the South,” one Alabama tenant farmer wrote to the Chicago Defender, “and I am trying my best to get out.”

The First World War ignited the Great Migration. The war drove demand for Northern-made industrial products. By extension, the war drove demands for labor. Recruiters came South to urge blacks to take Northern jobs, promising high wages and better living conditions. Black newspapers like the Defender reinforced those messages, encouraging black Southern readers to break free.

From farms and small towns, black men and women boarded the Illinois Central rail line, bound for cities like Cleveland, Chicago, and Detroit. My parents, who arrived in Detroit in the late 1960s, were among those migrants. In Detroit, my father first worked as a day laborer, loading produce trucks at Eastern Market. My mother worked as a maid in the wealthy Detroit suburb of Birmingham. Eventually, my father graduated from Wayne State University with a marketing degree and went on to lead the sales and marketing division for a beauty supply company. My mother graduated from Wayne State University with a business degree and worked for the National Bank of Detroit for 38 years.

My parents left Alabama, the place. They made good lives in Detroit. But they never left Alabama, the ideal.

My parents left Alabama, the place. They made good lives in Detroit. But they never left Alabama, the ideal. Not altogether. When my father drove to Alabama, he talked of going “down home.” That return was about reconnecting with cultural roots and showing off children. For me, the trip was about a shoe box packed with fried chicken, potato salad, and drinks, enjoyed over lunch at tin-topped rest stops. On the drive, my brother and I jockeyed for station wagon seat space, and slept on floor pallets in the way back, as crayons melted in the sun. We watched from a car window, awestruck, as the roads turned to red clay and the pines grew taller and taller. Even though I grew up in Detroit, Alabama resonated. It was about suppers of fresh greens, black-eyed peas, and homemade corn bread, served around four in the afternoon. It was about honeydews and watermelons, picked from a nearby field. It was the sound of rain on a tin roof. And squeaky screen doors, flanked by dirt dobber nests. It was about the dark, about how it gets so black in the country that the stars seem to multiply a thousandfold.

Alabama was about front porches and farm cats and stories of mules and cotton picking. It was about aunts with warm arms and sweet accents. It was about knowing I was going to be bored in the middle of nowhere, where the TV signal was sketchy, but then finding, always, something exciting to explore. No matter how much I came to love Alabama on those trips down home, Detroit was my true home. And I was proud of its history.

The children of migrants transformed the North. They dominated sports and music. Berry Gordy, the grandson of a white Georgia plantation owner, founded Motown. Running Back Jim Brown, of St. Simons, Georgia, ruled the NFL during a nine-year run with the Cleveland Browns. Those children of migrants also transformed politics in the cities to which their parents moved.

Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Southern-born mayors took the reigns of Northern cities. By 1967, Walter Washington, born in Dawson, Georgia, the great-grandson of a slave, served Washington, DC. Kenneth Allen Gibson, born in Enterprise, Alabama, was elected mayor of Newark, New Jersey in 1970. Tom Bradley, born outside Calvert, Texas, also the grandson of a slave, was elected mayor of Los Angeles in 1973. In 1974, nine years after my parents landed in the city, Detroit elected its first black mayor, Coleman A. Young. The eldest of five children, he was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Many black Southerners migrated north from the Jim Crow South to escape the drudgery of farm work. That said, they couldn’t deny the farm knowledge they had accumulated. Recognizing that one of the most effective ways to feed the working poor was to equip them with tools to grow their own, Mayor Young announced, in 1974, the Farm A Lot program. A precursor to urban farming programs of today, the program provided seeds, seedlings, and tools for tilling urban farm patches. And it inspired complementary efforts.

A precursor to urban farming programs of today, the Farm A Lot program provided seeds, seedlings, and tools for tilling urban farm patches.

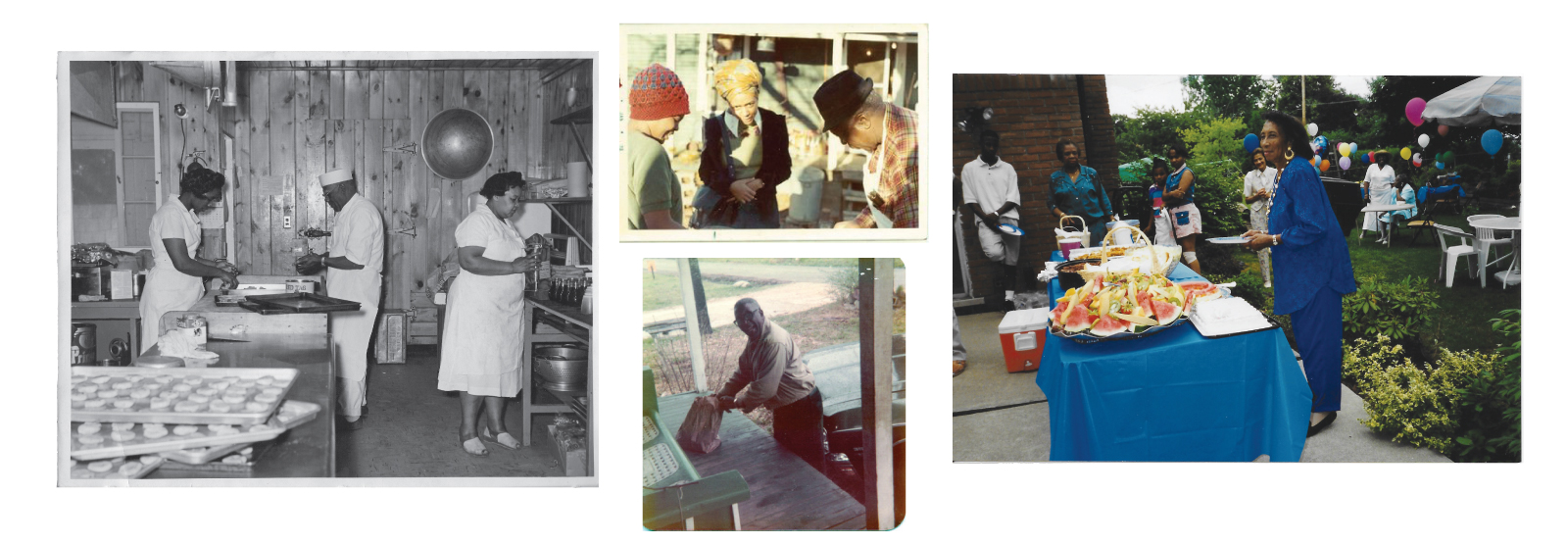

Beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s, an informal network of Detroit grandmothers known as the Gardening Angels set up community gardens to provide refuge and sustenance. These women grew backyard crops for their families. They also grew for homeless shelters and others in need. Working vacant lots and abandoned industrial sites, they farmed urban Detroit and demonstrated how that work reconnected their children of the asphalt to the earth.

This Detroit history motivates me, today, to change perspectives about food and encourage difficult conversations about race and capitalism. Detroit is the right place to do this work. The Detroit urban agriculture movement is now recognized worldwide for its training programs and initiatives, ranging from bio-intensive growing strategies to solar passive greenhouses. Detroiters now recognize the value of vacant land. Residents have turned abandoned lots into productive agricultural resources. Mini farmers markets are springing up citywide, providing Detroiters with fresh, organic food.

I grew up in Detroit, after the 1967 rebellion, at a time when whites were fleeing the city, and auto manufacturing closures had hit the workforce hard. Much of the current rhetoric about those moments conveniently ignores race, concentrating instead on macro-economic trends. Usually when race is addressed as a cause for Detroit’s decline, the phrases used are “racial tensions” or “the racial divide.” Nonsense. Detroit blacks have suffered sustained and systemic racial discrimination. Even today, the blatant racial separation in Detroit affects food access and drives health disparities.

Today, I get my agricultural inspiration from Detroit. I look to the courageous, conscious people now developing and testing models of prosperity for people of color, defined by networks of corner stores, sanctuary restaurants, and food cooperatives. I am inspired by Detroit activists, deeply rooted in the soil and committed to building community. And I am inspired by Detroit, where the children and grandchildren of so many Southerners now live and work and strive.

As a descendant of sharecroppers and a daughter of the Great Migration, I work aggressively to strengthen the value chain of culturally appropriate foods. Working in Detroit, I focus on sovereignty, accessibility, and availability. At FoodLab Detroit, a membership-based network of 200-plus food processing and retail businesses, we strengthen the local food economy, promote healthy lifestyles, and build businesses that make a positive social impact in their community.

We gather around food to talk. We talk at community dinners, in kitchens, and at workshops. Those conversations are the foundation for this resilient community we are constructing. Working alongside each other, seeing and valuing what each other does, we heal our relationships. We share in successes and lift each other up. We give voice to stories muted in the margins. And we celebrate.

At one of our monthly meetings, a new visitor took me aside to say this was the first gathering of entrepreneurs she’d attended in Detroit that referenced racism or income inequality. I know these conversations are uncomfortable for some of our members. To encourage dialogue, we maintain a welcoming environment, offering value and benefits to entrepreneurs, while staying committed to dialogue and creative action.

FoodLab Detroit believes that diverse, locally owned and operated businesses are key drivers in vibrant, resilient, healthy communities.

We believe that diverse, locally owned and operated businesses are key drivers in vibrant, resilient, healthy communities. In Detroit, where too many African-Americans suffer from preventable diet-related illnesses, our member business Detroit Vegan Soul, serves a plant-based diet of nutrient-dense leafy greens and legumes like butter beans and black-eyed peas. They inspire many, demonstrating how to use the power of their business to solve health and environmental challenges.

Those of us who work in the Detroit urban agricultural movement are clear about tangible benefits. Our work provides fresh nutritious food, beautifies neighborhoods, creates social capital, advances economic development, stabilizes communities, and provides sustainability. Our work provides concrete examples of alternative, value-oriented means of securing our livelihoods.

As an activist, organizer, and nonprofit leader working for food, economic, and environmental justice, I seek to honor the urban agricultural movement in Detroit for its role in leading me back to my culture, back to where I come from. It has been in the spaces of food justice; the garden, the kitchen, the market, the land, that my ancestors have re-visited me, whispering universal knowledge that strengthens my blood, my hair, and my hands.

I come from Black people who grew their own fruits and vegetables, ate whole foods, and emphasized what we now call food sovereignty. Today, I regret that I have lost a connection with Southern foodways. I don’t just miss the collards and sweet potato pies. I mourn the neck bones and pig’s feet. I regret that I can’t whip up souse from scratch like my Big Mama used to. My niece may never eat this food. She doesn’t need to head “down home” to visit extended family. Her parents are Northern. And so is she.

We first- and second-generation Northerners use shorthand to describe our unique cultural experiences “down South.” That shorthand is now slipping into disuse. Those links are now breaking. As the generations roll on, descendants are unmooring from “the old country.” It makes me melancholy. I hope I never ever forget the great effort that my ancestors made to leave the South. May I never forget the perseverance, courage, and suffering they endured to make Detroit a place of safety and freedom and agricultural possibility.

Devita Davison is executive director of FoodLab Detroit, a nonprofit working to make good food a reality for all Detroiters.