The Migration Less Traveled Mom and Dad believed that our crossing barriers would assure a fully integrated future.

During a mid-50s Christmas visit, Leana Peters Battle, a 1915 Spelman College graduate, shares the front steps of the Dalton Vocational School principal’s residence with granddaughters Pat Battle (Seneca, South Carolina) and Dalton granddaughters. Battle Family Photos.

![]()

by Donna Battle Pierce

![]()

Almost a decade ago, on a visit to my father’s house in Columbia, Missouri, I popped my head into his home office.

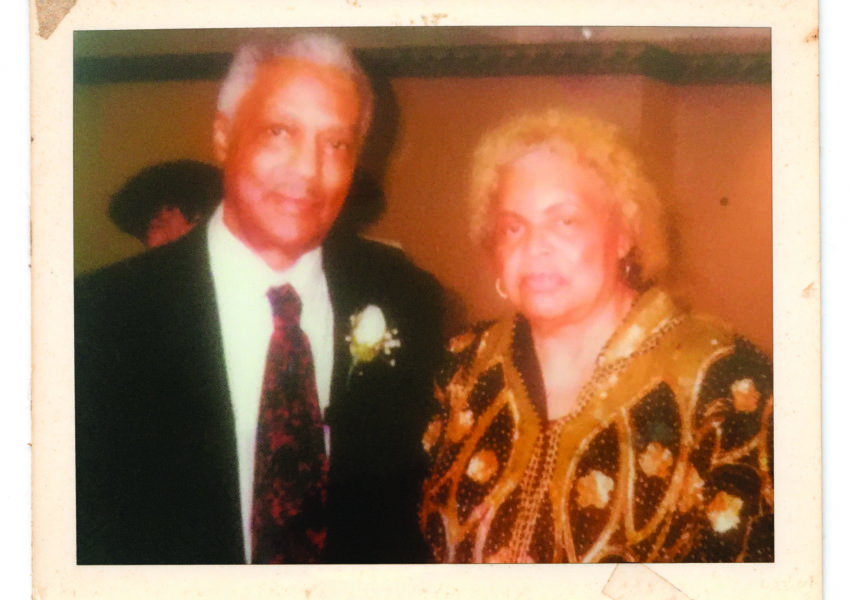

I was just in time to catch his wistful smile as he sat behind his desk, looking at a framed photo. It showed Muriel and Eliot Battle—Mom and Dad—a few months after they completed the first leg of their Great Migration journey. It was one of their favorite images.

The year was 1950, and the HBCU graduates in the photo were newly married. Dad was a World War II veteran. Both of my parents were Gulf Coast natives who came from distinguished professional families made up of physicians, lawyers, educators, musicians, and writers. My paternal great-grandfather Charles Peters was close friends and business associates with Booker T. Washington—Washington stayed in his home when he visited Mobile to meet with the city’s leading entrepreneurs. In 1891, Peters constructed a two-story wooden building on Dauphin Street in downtown Mobile to house his three businesses: an insurance company, a general store, and a furniture retailer. With the profits from these businesses, he sent his nine daughters and sons to college.

After their June 1950 wedding, both sides of the family expected my parents to settle in Mobile where, like previous generations, their children would benefit from a strong family legacy to which they would one day contribute. Despite this, Mom and Dad felt certain of their decision to leave.“We made a pact to raise our children away from segregation,” Dad has been described as repeating. There was also an element of spiritual calling. As a college student at Tuskegee, Dad, who had grown up with a fascination for neighborhood vegetable gardens, got a campus job working on the farm and in the stables. This brought him into regular contact with George Washington Carver over the next two years. Dad explained his enormous appreciation of Dr. Carver using words people would later use to describe him. “It was exciting to see him at work and to converse with him…a man could study and reach the heights he attained, and yet remain humble,” Dad wrote in his 1997 book, A Letter to Young Black Men. Carver died in 1943, the year before Dad graduated from Tuskegee. By that time, Dad dreamed of someday raising a family in a rural setting. “By the way,” he told me decades later, “Carver was born in Missouri—just like you.”

“We made a pact to raise our children away from segregation.”

When my parents relocated to Missouri, both took jobs as educators. First, they lived in Poplar Bluff, where I was born during Easter vacation 1951. From there, we moved briefly to Boonville, and then settled in Dalton, Missouri, where my father served as the principal at Dalton Vocational School. The school was deemed the “Tuskegee of the Midwest” by its founder. Dalton was the only high school available for Black students from several counties. Each weekday, students took long school-bus rides to the 123-acre campus, which maintained a working farm, complete with horse stables, hog pens, and hen houses.

Despite their urban Mobile, Alabama, roots, both of my parents remembered feeling right at home on Dalton’s campus. My father referred to a child’s dawning consciousness as the moment “when their lights came on.” The switch flipped for me at Dalton. I vividly recall gathering eggs from the chicken house behind the principal’s residence, watching senior agriculture students digging pits for whole-hog barbecue, and endlessly cracking and shelling the famous Chariton County pecans from the nearby pecan grove with my sister Carolyn.

Though she had grown up with the vibrant flavors and ingredients of the Gulf Coast, Mom surprised our rural neighbors with her sincere interest in learning their dishes and traditions. Before she passed away in 2003, Mom recounted one of her most treasured compliments, a comment made by a Dalton faculty wife long ago: “You don’t act like a city girl in the kitchen!” The woman was referring to my mother’s chicken- and turkey-plucking skills, as well as to the pies Mom baked with wild persimmons and local apples. She also added brisket, chili, wild rice, corn on the cob, and frozen custard to her repertoire.

At the same time, she insisted on passing down the dishes of our Creole and Southern family history. Along with their wedding silver and china, my parents had moved to Missouri with handwritten family recipes and treasured ingredients like gumbo filé, hot sauce, and Creole mustard. Those passed-down recipes always came first at our house.

My parents maintained close correspondence with family and friends on the Gulf Coast after their move to Missouri. Among other topics, they wrote about the segregation that persisted outside the South. During our time at Dalton, we returned to Mobile for holidays. I remember sharing the family station wagon with carefully wrapped and chilled turkeys, ducks, and pheasants my mother had slaughtered and dressed on the farm. My grandmothers were always excited to receive these gifts, which seemed exotic in Mobile at the time.

Returning to the Gulf Coast meant reunions with our extended family over long meals. On these visits, both grandmothers fervently encouraged me to consider Mobile my hometown. I couldn’t fully understand the passion of their exhortations, but I remember feeling proud and doted upon each time they claimed Mobile for me.

Dalton closed in 1956, following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision ending de jure segregation. Our family moved to Columbia, where Mom became a first-grade teacher and Dad worked as an assistant principal at Douglass High School before integrating Columbia’s David H. Hickman High School as its first Black administrator.My parents raised four children in Columbia at a time when that part of Missouri, which had been founded by Southern enslavers, still bore the nickname “Little Dixie.” They shared a vision that Carolyn and I, their two eldest children, would spend the late 1950s and 1960s peacefully integrating Columbia’s public schools. Beyond the classroom, we would join every club, orchestra, and extracurricular activity our progressive mother had decided needed the presence of a “smart Negro girl,” as we referred to ourselves at the time.

Mom and Dad believed that our crossing barriers would assure a fully integrated future, and not just for our own family. Looking back, I remember working hard to shelter them, particularly Mom, from the hurt and pain Carolyn and I felt from our daily battles with racism and segregation. Neither of my parents knew how cruel some of our classmates could be. Our school curriculum left out crucial parts of Missouri’s racial history, from Klan activity and lynchings to triumphant stories of Black entrepreneurship. When I went shopping with friends, I was not allowed to try on clothes or shoes in white-owned stores. Even as a child and a teenager, I respected my parents’ sacrifices. And I wanted to protect their feelings.

Mom and Dad believed that our crossing barriers would assure a fully integrated future, and not just for our own family.

I never told my parents about the conversations I’d have with my grandmothers during our visits to Alabama. My grandmothers understood why my parents left. But they wanted me to see Mobile as a place where I had deep, honest roots—roots that my elders longed to nurture. My maternal grandmother patiently taught me to cook her own special gumbo, the family yeast rolls, shrimp Creole, and fruitcake on those trips, too. I was about ten years old when Granny anointed me the grandchild who had earned the opportunity to follow her footsteps in the kitchen, learning family recipes and food traditions to pass down to future generation. Some six decades after lessons began, I need only close my eyes to experience vivid memories of my happiest times spent at her home in Mobile’s Down the Bay neighborhood. Her kitchen had long, breezy, cotton curtains in yellow and white; well-scrubbed appliances; a pantry that was always stocked; and an efficiently organized collection of utensils, cookware, cutlery, and dishes. Granny insisted we speak softly in the kitchen “to create a welcoming space for our ancestors.”

Today, from my home in southern California, I write a regular column for Lagniappe, Mobile’s independent weekly newspaper. I’m also teaching the family cookbook to my youngest relatives. Now I understand that I can claim more than one place as my hometown. Migration does not have to mean permanent exile. My grandmothers knew this all along.

Donna Battle Pierce, a former SFA board member, has written the syndicated food columns “Black America Cooks” for the Chicago Defender and Ebony’s “Hungry for History.” A former Chicago Tribune test kitchen director and assistant food editor, she lives in Santa Monica, California, where she is writing a book about longtime Ebony food editor Freda DeKnight.

SIGN UP FOR THE DIGEST TO RECEIVE GRAVY IN YOUR INBOX.