Is The Birdman’s “Southern” Story Too Much For New England?

“Just be quiet, give me my chicken, and let me pay and be on my way.”

by Mark Joyella

The pizza place with its back to the tracks shakes as Amtrak’s Northeast regional rumbles by on its way from Boston to New York. My young daughters watch the train for a moment, but it’s cold, so the girls, my wife, and I go inside and ask for a table upstairs. There, model trains loop and lovingly-detailed miniature towns suggest daily life along the Connecticut shore in the 1940s and 1950s. Tiny plastic people hail cabs and fish from bridges. A hand-painted woman glued to a tiny dock paints a watercolor of the Long Island Sound.

Real life here on Connecticut’s Gold Coast—a ribbon of seaside suburban towns with good schools, artisan cheese shops, and farm-to-table restaurants that occasionally land a paragraph or two in The New York Times—is at times as idyllic as the diorama in the pizza joint. And often, just as fake.

We’ve stopped in for a pie before going shopping, and I note that the menu boasts three different pizzas topped with fresh clams, sourced from a nearby fish wholesaler that’s been in business since 1930. The clams remind me of a conversation about oysters I’d had weeks earlier with a local historian, Ramin Ganeshram.

I was sitting with Ganeshram at a long table in her office on the second floor of the Westport Museum for History and Culture, housed in a home built in 1795. Light poured through a twelve-paned window as we talked about food, specifically how willing anyone really is to learn the origin story of the food they eat or the history of the people who harvested it.

“Oysters are a great example,” she said, marveling at the upscale rebranding of oysters, despite their tradition as subsistence food, easily foraged at the waterline in towns like this by indigenous people and enslaved Africans who once walked the same beaches where my daughters squeal at the sight of tiny crabs emerging at low tide.

Imagine, Ganeshram says, “you are a native person whose land has been taken and your tribe has been decimated, and your ability to move through tribal territory to hunt venison or gather has been taken away from you. At least you can walk along the shore [of what is now Compo Beach or Jennings Beach] and gobble down an oyster. Is that pleasant? It’s not.”

Would seeing oysters as the foraged food of enslaved people make that $27 appetizer of broiled bluepoint oysters and anchovy butter any less satisfyingly indulgent? Can an origin story spoil the way food tastes?

Chef Chris Scott recently asked himself similar questions. Capitalizing on a successful Brooklyn restaurant and a turn on Top Chef, Scott charged up I-95 into Connecticut’s Fairfield County, a suburban market dominated by gastropubs, wine bars, and French restaurants. Scott would draw diners with the food that made him famous: elevated Southern soul food. In June 2019, Scott debuted Birdman Juke Joint in the Bridgeport neighborhood of Black Rock, just over the town line. The location is just a few miles from our home in Fairfield, a town of handsome colonial homes, many of which bear markers declaring they were spared when the British burned the town in 1779.

Like Scott, my wife and I moved here from Brooklyn in search of space to stretch out and raise our children. We’d been ready to leave the city, but we wonder sometimes what we traded to get here, where one of the few problems facing the public schools is a lack of diversity. So we were thrilled to welcome Birdman, whose Instagram page promised the “best fried chicken in the North.” We anticipated more of the deviled eggs topped with crisp collard-green “cracklin” that we’d tasted at Scott’s prelaunch pop-up, and the brown sugar-buttermilk biscuits we watched him make on TV.

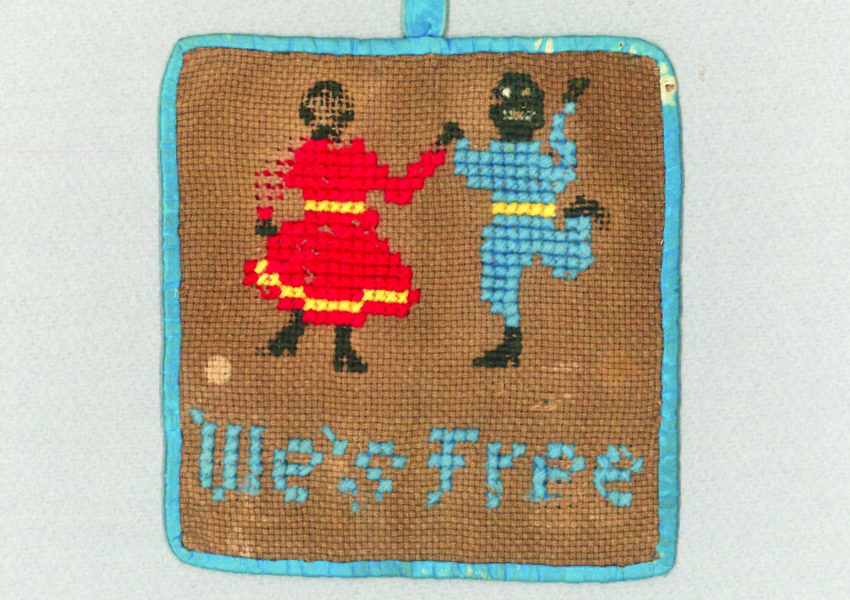

For months, we watched as Scott transformed the space that had previously been a saloon called the Copper Fox. Scott brought the space down to brick walls and wood floors, and then filled in with reclaimed wood booths and a bar topped with corrugated metal meant to evoke the chicken shack of Southern road trip fantasies. In the final weeks before opening to people lined up at his door, Scott covered the walls with photos, black-and-white images of six generations of his family, stretching back to his ancestors who endured slavery.

Shortly after Birdman opened, my wife and I sat in one of those pallet wood booths and wondered what our neighbors, with their Volvos and Vineyard Vines, would think of the place. We often looked at the names of the kids in our four-year-old’s preschool classroom: Adelaide, Andie, Tyler, Emma, and Finn.We wondered if we’d taken a risk moving our girls away from Brooklyn, where our nine-year-old’s preschool class photo is as multicultural as the city itself, and at the end of the day I’d wait for my daughter alongside Muslim moms who wore the niqab.

I believed my hometown could benefit from eating Scott’s food—and learning about the Birdman, who tended birds on plantations during slavery, and once slavery was abolished, used those skills to become his own boss. “The story of the Birdman, through triumph and resilience—that was going to be the story behind [the restaurant],” said Scott.

He had loved sharing his family’s food and history at the restaurant in Brooklyn, where he told me diners were open to wanting to know the story. How did this plate of food get here? How many hands and cultures did it have to go through to get where it’s at? But would folks in Connecticut listen to a story about slavery?

My mind went back to that conversation with Ganeshram. “I’m a believer that food is a good way to get people to open their minds to something cultural they might not have otherwise considered,” she said. “Because you’re really satisfying an immediate need first that’s very sensory. But in doing so, you might become curious. So, it can be a lever to open up these cultural questions.”

I knew people would enjoy the Birdman’s chicken. But would they stomach his story?

Months earlier, I’d spent a day poring over papers at the Fairfield Museum and History Center, working at a long table under the eye of a stern colonial-era woman gazing down at me dismissively from an oil painting. That was the day I learned about Amos, a boy almost my daughter’s age. His life is recorded in a pair of boxes labeled “Adams Family Papers, 1712-1889,” an otherwise mundane collection of legal and financial records of a family that settled in Fairfield in the 1650s. The Adamses were farmers, storekeepers, schoolteachers, and bankers. The sales receipts and records they left behind capture life in my town three centuries ago, each will, codicil, and survey filed in the very same town hall where my daughter and I had paid $8 to get our new puppy a license.

Among the Adams Family papers—Box 1, Folder E—is a contract, written in the blasé municipal formality of the time, with which every sale of land, cider, and calf skins was recorded for posterity. My eyes scanned the lines, up and down the swirls and slashes of someone’s lilting script until the blunt, ugly words forced me to stop, go back, and read them again. “A Certain Negro Boy Named Amos Aged Eight Years,” the document states with all the emotion of a land deed, recording a piece of routine business between Joseph Hanford and Nathaniel Adams, Jr. Amos was sold for five British pounds.

My heart pounded and my brain stalled, flooded with the loud static of confusion. Amos, this little boy, had he been alive today, would very possibly be one of my daughter’s classmates at Roger Sherman Elementary School a few blocks away, relentlessly telling his parents that he did, in fact, need his own phone.

I had lived in this town as a boy, gone to school here, and somehow didn’t learn about Fairfield’s legacy as one of Connecticut’s biggest slave-owning towns until decades after I graduated from college. I’d known about slavery, of course, but only as someone else’s story, not my own. I’d been taught about good guys and bad guys, and I’d learned that here, in this place, we were very much the good guys.

“It is human nature to want to reject facts about one’s town that feel very unpleasant,” Ramin Ganeshram told me when I mentioned Amos and the emotions his story raised in me. I’d been lied to. “I do think there was a self-consciously deliberate erasure of the history of people of color, particularly black Americans here in Fairfield County and in Connecticut at large,” she said.

I knew people would enjoy the Birdman’s chicken. But would they stomach his story?

For Chris Scott, fitting the Birdman’s story into this tidy good-guys-and-bad-guys frame proved tricky, more than it had been in New York City, where Scott felt he “was certainly much more free to tell stories of slavery and my family.”

Did that mean Scott felt less free to speak of slavery in Connecticut? He told me about a pop-up fried chicken dinner he’d hosted in West Hartford ahead of Birdman’s opening. The dining room fell quiet as Scott thanked everyone for coming out to sample the food he’d serve at the new restaurant. Scott spent a few moments telling the story of the Birdman—only to learn later that linking the meal to slavery had made some people uncomfortable.

“At that point, I felt like maybe I had to watch what I would say,” Scott told me.

Are we, in New England, invested in seeing slavery as a Southern sin, another proof point of our place in history as the good guys? Or is it more than that—do we refuse to see slavery at all, for fear a real examination of the history would mean seeing an economic system that served people here, far from the plantations of Belle Grove, Nottoway, or Monticello?

“As a nation, we have not adequately, factually represented what happened,” Ganeshram told me recently, speaking not just of the South but of children like Amos, sold right here in my town.

Birdman Juke Joint opened in January 2019 to droves of eager diners and buzzy reviews. The faces of Scott’s family members watched from the wall. Diners dug into cornmeal-crusted catfish, and nobody was forced to make the painful connection between the food and the legacy. Even the word “slavery” had slipped just off screen, the menu, and website in recent months. They present a softer story, saying just that “at Birdman we share the richness of history and the abundance of flavor that is the essence of authentic Southern cuisine. We’re telling the cultural story of resilience and triumph through the humble bird.”

Scott still believes a restaurant without a story risks becoming a caricature, as authentic as the viral chicken sandwich that had folks lining up at Popeyes—and Scott’s been thinking a lot about that, and how comfortable or uncomfortable he is dialing down his family’s story to keep his customers happy. Can he run a successful business catering only to those people who want the food—without the story?

“There are folks out there that just simply want me to fry chicken,” he told me. “They don’t really care about the story. Basically, just be quiet, give me my chicken, and let me pay and be on my way.”

Mark Joyella is a political journalist and regular contributor to Forbes.

Illustrations by Lindsey Bailey

SIGN UP FOR THE DIGEST TO RECEIVE GRAVY IN YOUR INBOX.