Highway 220 Daddy Lessons Boiled peanuts and peaches by the Carolina roadside

by Cynthia R. Greenlee

My Father forgets to chew. The nursing assistant tells him, “Chew, chew, chew.” Then, she reminds him to swallow—a command that swells with gentle forcefulness at each repetition. He eats the “mechanical diet” for people who have difficulty swallowing, and today’s meal is a beige mishmash of minced chicken and potatoes, served with a thickened soda.

![]()

Not for the first time, I think that there is a difference between feeding and eating, between eating for pleasure and eating for maintenance. I watch the thrice-daily drama of mealtime on my regular visits to the retirement facility that is now his home. It usually involves his refusal to eat, the word “slop,” and demands for special dishes—as if the nursing home dining hall is run by short-order cooks or personal chefs. If it’s a “good/bad day,” meaning he’s lucid enough to speak, but agitated enough to demand without inhibition, he will complain loudly about the lack of salt and pepper in his Salisbury steak. He’ll say, “No seasoning,” and then point to the kitchen. “No black people in there.”

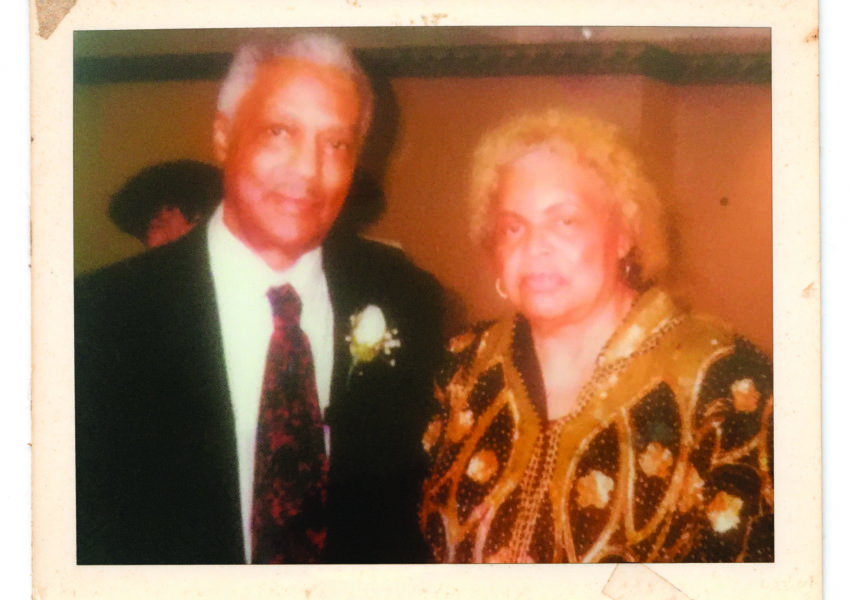

I secretly enjoy these uncomfortable exchanges because my father has always been a “race man.” His outbursts remind me that some things have not changed. Before dementia turned my father into a person whose basic bodily functions need prompting, he was a doer. A master gardener, an eater, and a patriarch, he commanded respect and took the wheel of our family’s sky blue Caprice Classic.

A few times a year, my mother loaded the car with suitcases, children, and pets. We headed south from Greensboro, North Carolina, down old Highway 220 toward my mother’s hometown of Lake City, South Carolina, to my grandparents’ farm, where there was still a barn of curing tobacco, fields of soybeans, and water pumps outside. My six-year-old self prayed for a rare fast-food stop at Hardee’s. More than a hot dog Carolina-style with chili, slaw and onions, I anticipated our roadside stops along the less busy stretches of Highway 220, where nearby small towns shared names with peaches: Hamlet, Biscoe, Ellerbe.

Memory is a fickle, suggestible thing, but I remember one trip in particular. I was just into my elementary school career, probably summer 1980 or so. I was old enough to recite the alphabet without singing it, but young enough that I still clutched thick, foot-long pencils to write. I wore lacy socks underneath my sandals. A man at a roadside stand outside Ellerbe, North Carolina, swatted a mosquito with one hand and handed my mother a small wooden basket of just-weighed peaches with the other. Sweat beads on his brow, he laid the change from her five-dollar bill on the counter. Young as I was, I knew that we would not be coming back to this fruit stand during next summer’s pilgrimage.

With as much certainty as I knew that Grandmother Daniels would have a seven-layer chocolate cake waiting for my arrival, I understood that not putting a black person’s change in their hand was an unsubtle insult. Daddy had taught me that much. No matter what the law said about equality, this white man with the permanent suntan and the choice peaches probably thought that touching a black woman’s hand—even the hand of the perfectly coiffed, brown-skinned Mary Tyler Moore lookalike who was my mother—was a breach of white supremacist etiquette. Or maybe it was an omission. After all, he was sweating. Maybe he was kind to not extend his moist, slippery hand.

Daddy was away from the car, stretching his legs in the shade, drink-eating peanuts and Pepsi from a bottle. Mom told him, “Let’s not stop there on the way back. I don’t like the feel of the place.” He put the glass bottle down carefully and hopped to his feet.

“Did he say something to you?” She shook her head, but he seethed in silence. I sat in the luggage compartment of the wagon, played with our fussy Pekingese, and strained to hear my parents’ hushed conversation over the furious whoosh of the air conditioner. During legal segregation, guides like the Negro Motorist Green Book advised black travelers of places they could dine safely or lay their heads while on the road. My parents had their own versions of these guides in their heads, memorized after the formal end of Jim Crow.

As we pulled away, Daddy squinted and eyed the food stand in the rearview mirror. My parents marked this location off their mental maps. There were racial rules, and there were road rules. I learned them in our station wagon, on pleather seats that sucked at the back of sweaty thighs—just as I learned how to eat adventurously as our family rolled through the Sandhills region of North and South Carolina.

My father has always been a didactic sort, who sees a lesson in every life event. He turned my allowance into an exercise in counting; I learned negative numbers years before my classmates because my father subtracted a quarter every time I failed to take out the trash or whined about picking scratchy squash in our garden. On our road trips, he pointed out changes in the land.

“Look at the soil. See that it’s lighter than in Greensboro? It’s not brown and it’s got red clay in places. It’s sandy, that’s why it called the Sandhills. And there’s more bushes, lower to the ground.” I looked out the window during the entire drive, not wanting to miss anything. Highway 220 marked one hemisphere of my childhood’s known universe. Bustling in the late spring and summer, when farmers supplied roadside stands with sun-warm produce, it was a route of wonder and plenty.

For me, happiness will always taste like a salted tomato.

A few miles outside Asheboro, North Carolina, my South Carolina–raised mother would sigh with anticipatory pleasure. Without raising my head from my pillow, I could tell that we had entered the boiled peanut zone. My father would stop the car multiple times, half-exasperated and half-amused that Mom needed to sample peanuts at different stands. “Her South Carolina is coming out,” he’d tease. My parents had a decades-long banter over which Carolina was best: North Carolina, with its history of poor dirt farmers, or the more patrician (according to my mother) South Carolina. My father came from the mountains of western North Carolina—a place where there were few black people, less arable soil, and a different food culture. My mother’s ancestors hailed from the Pee Dee country of northeast South Carolina, where enslaved people had once worked large plantations. Boiled peanuts were reminders of West African contributions to the regional diet. Mom bought the peanuts hot and steaming from the pot, or she chose the “rested” boiled peanuts—cold, salted, and delightfully clammy. Either way, we’d wait for her judgment.

“Not enough salt,” she’d say of a batch in a plastic bag. “Too hard,” she dismissed another. The gold-standard boiled peanut needed to be almost fleshy, firm but giving, same as her parenting style.

We would soon cross the Herring and Peach Line around Richmond County, North Carolina, a border as tangible as the state line. The swarm of gnats that often accompanied the briny, smoked herring announced that we had officially left our suburban Piedmont. We’d gorge on roadside treats like pastel-colored taffy in the cooler months, strawberries and voluptuous tomatoes in early summer. I clamored for milky local ice cream stuffed with chunks of frozen peaches, but my father always steered me from dessert to produce.

My parents usually made a beeline to the roadside stands that were little more than funeral-home tents stretched over a few chairs, a cooler, and crates of fruit. Startup affairs that, more often than not, were run by black farmers. “Let’s stop there,” my mother would urge, based on a mysterious calculus that involved the likelihood of boiled peanuts for sale, a clean bathroom (if there was one), and a warm welcome (generally evidenced by the presence of other black motorists). My parents had their observations about which stands had managers who talked down to their black helpers; which vendors looked like good ole boys, but would put your money in your hand and not on the counter; and the rare ones who were “safe” and remembered us from the last summer, or at least pretended that they did.

My father would exit the car first and shoot the breeze while my mother would do reconnaissance, looking for a basket of peaches that didn’t conceal the bruised fruits at the bottom. Daddy would browse, keep an eye on us, and make small talk all the while. “How are the peaches today? Was it a good year? It’s hot out there. And where’s your daddy? I always liked talking to him. Oh, he passed on? He made the best boiled peanuts.”

To my sisters and me, Daddy’s roadside chats and his insistence that we leave the air-conditioned car on 100-degree days were evidence that the heat had caused him brain damage. But I never regretted it once I exited the car’s frosty bubble. At some roadside stands, the staff would crack open a watermelon, and they reserved special mini-wedges for children. Or they’d give you a tomato slice and a tiny package of salt as preview of their wares. For me, happiness will always taste like a salted tomato.

This was how Daddy connected with the land. Where he grew up, in the Swannanoa Valley, everyone had a garden. His family’s produce supplemented the meager earnings of my grandfather, a disabled man who worked as a handyman to support his brood of ten, and helped support my grandmother, who labored on and off as a domestic.

Even after my father graduated from college and moved to the city, he loved to tend a small batch of our backyard. He filled it with tall stands of beans strapped to wires and grapevines that produced the smallest, sourest fruit known to man. This was his playground, the place where he could experiment with fake owls that were supposed to scare away the rabbits that mowed down his spring lettuces. He shed the suit he wore to his social worker job, put on a thin, white Hanes T-shirt and rough feed store jeans, and would holler at neighbors tending their small city gardens on the other side of the fence. Daddy would sit on the ground and look for whatever bug was sucking the moisture from his first cantaloupe vines, take samples to his local extension agent and ask questions. He’d come back and report the findings to us. “You need to know this stuff for one day, when I’m gone,” he would say. And when I went away to college in August, he’d send me off with a plastic grocery bag of tomatoes. His love grew on vines: a little abrasive and scratchy, but natural and alive.

Our road trip excursions were part of our schooling, too, my father’s way of “learning” his city-raised children to appreciate the rural South and giving due to the people who worked the land. I learned that same lesson when I went with Daddy on Saturdays to Southern States, the feed store that sold dried beans, pickles in a barrel, and peppermint knots. “There’s no difference between a man in overalls and a man in the business suit, except for their clothes, their money, and what dumb people think about them,” Daddy said in some iteration on every road trip. “Even if it looks like they’re just sitting out there doing nothing, it’s hard work sitting someplace where it’s ninety degrees in the shade.”

Our road trip excursions were part of our schooling, too, my father’s way of “learning” his city-raised children to appreciate the rural South and giving due to the people who worked the land. I learned that same lesson when I went with Daddy on Saturdays to Southern States, the feed store that sold dried beans, pickles in a barrel, and peppermint knots. “There’s no difference between a man in overalls and a man in the business suit, except for their clothes, their money, and what dumb people think about them,” Daddy said in some iteration on every road trip. “Even if it looks like they’re just sitting out there doing nothing, it’s hard work sitting someplace where it’s ninety degrees in the shade.”

As I grew older, he would give me a few dollars so I could buy my own produce to share. He’d make sure that I greeted black vendors before the transaction, put my cash in their palms, and said thank you. And then—because my father was nothing if not frugal—he’d ask for his change back.

When we chatted with folks at stands, we weren’t just standing under their canopy, paying for fruit, and wishing for a cool wind. We appreciated the produce and the producer, the people who could tell you the week and month by which variety of peach was ripe. We paid homage to the small farmers who struggled to stay afloat when the state built a bypass that diverted traffic from the small towns nourished by these food stands. Later, we became one of those New South families that took the road more traveled. The line of black asphalt got us to Grandma quicker. It was a matter of convenience for my parents: less time spent in a stuffy car with three children.

I haven’t traveled the old 220 for years. Now, it seems a rude violation to drive that road without my father taking lead. He sits in a wheelchair, unable to move on his own and occasionally unable to remember which hallway will lead to his room. Our journeys together now are short affairs. I push him in that wheelchair from dining hall to his room. When he’s feeling cantankerous, he doesn’t want to return to his room and literally puts his foot down to stop me from rolling him forward. He demands that I roll him out the door and take him to the bank, the Walmart, somewhere other than here.

Mom walks alongside us, and I can feel her worrying that he didn’t eat enough. An hour after the dinner he didn’t finish, I watch him eat a Magic Cup, a frozen, ice cream–like treat packed with protein. It is the one thing he will consume with gusto. My father—who demanded sturdy, home-cooked meals and would brook no leftovers—slowly spoons it to his mouth, sometimes forgetting that his hand is in the air. I think, not for the first time, that happiness tastes like a summer tomato and loss tastes like that peach ice cream Daddy never let me eat.

Cynthia R. Greenlee is a journalist, a historian who researches African American legal history in the South, and a diehard fan of peach ice cream. She developed this piece at the SFA’s 2017 Rivendell Writers’ Colony Workshop.