CAN I GET A WITNESS? The righteously, radically Campbellite core of Nashville

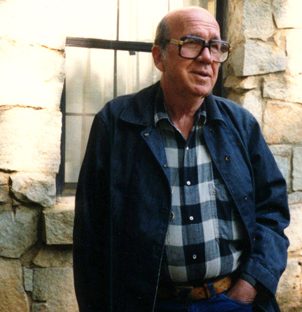

by David Dark (Gravy, Fall 2016)

We Nashville natives are often ashamed of how saturated our city is in for-profit religion. From religious publishing to religious music to motivational speaker-preachers, we’re a magnet for people who feel compelled to speak on God’s behalf and who confuse, from time to time, the voice in their heads for the voice of the Holy Spirit. This makes for a lively mix of newcomers, some of whom casually preface their migration stories with “When the Lord called me here…” to pursue a calling—be it as musician, minister, or restaurateur.

When the label head or the CEO-pastor inevitably lets them down, these wide-eyed followers become weary pilgrims. They are my favorite people to talk to. I want to simultaneously honor their disillusionment and disenchantment while inviting them to think again about the longsuffering sincerity of Nashville’s best self, a sweetness that lives here despite the silliness and the lies. I want to tell them that a visit to the Grand Ole Opry for a New Yorker piece inspired Garrison Keillor to create A Prairie Home Companion. That the songwriting, session-musician culture at work here, besides drawing in folks like Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Elvis Costello over the years, has filled its own reservoir of artfulness and wit. And that some of the earliest and most widely publicized lunch-counter sit-ins occurred here.

When the label head or the CEO-pastor inevitably lets them down, these wide-eyed followers become weary pilgrims. They are my favorite people to talk to. I want to simultaneously honor their disillusionment and disenchantment while inviting them to think again about the longsuffering sincerity of Nashville’s best self, a sweetness that lives here despite the silliness and the lies. I want to tell them that a visit to the Grand Ole Opry for a New Yorker piece inspired Garrison Keillor to create A Prairie Home Companion. That the songwriting, session-musician culture at work here, besides drawing in folks like Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Elvis Costello over the years, has filled its own reservoir of artfulness and wit. And that some of the earliest and most widely publicized lunch-counter sit-ins occurred here.

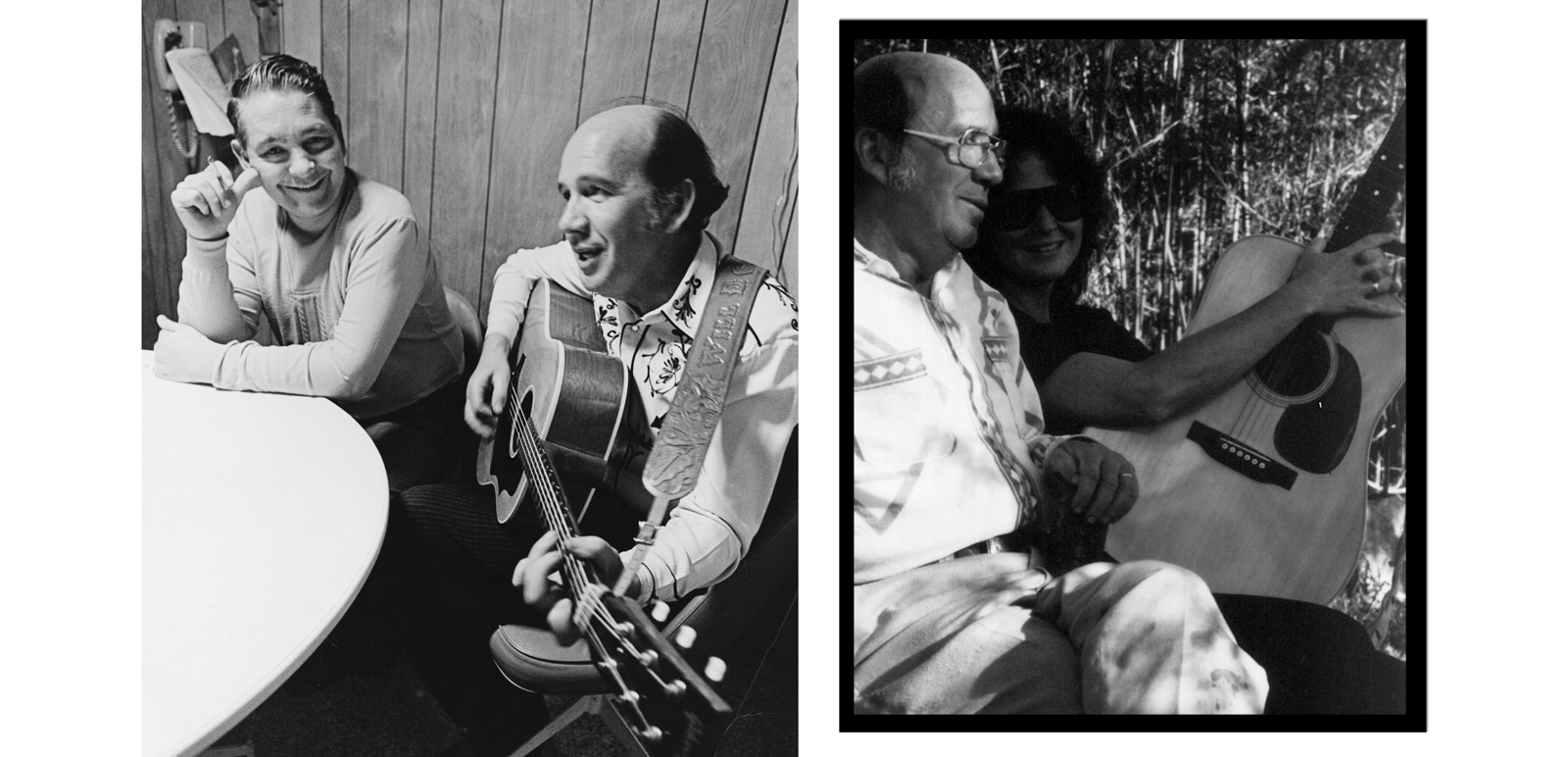

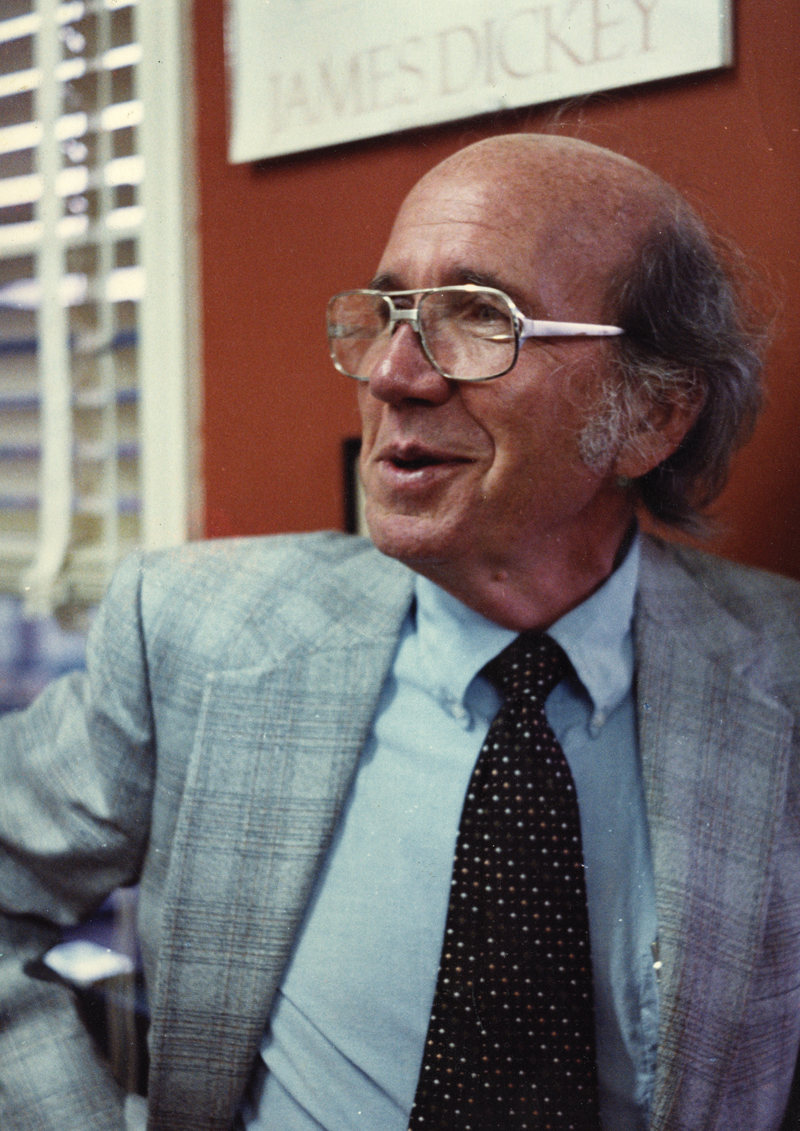

Each of these phenomena strike me as intimately related and uniquely Nashvillian. I have in mind a man who holds together the Civil Rights Movement, theology, and country music. Reverend Will D. Campbell, a friend and close associate to Martin Luther King Jr. and Kris Kristofferson, was our underappreciated bridge figure. He dismissed our divisions and brought all to one table to break bread together, literally and figuratively.

Each of these phenomena strike me as intimately related and uniquely Nashvillian. I have in mind a man who holds together the Civil Rights Movement, theology, and country music. Reverend Will D. Campbell, a friend and close associate to Martin Luther King Jr. and Kris Kristofferson, was our underappreciated bridge figure. He dismissed our divisions and brought all to one table to break bread together, literally and figuratively.

Campbell first appeared before me in the pages of Rolling Stone, a breed of God-talking Southerner I didn’t know existed. Here was a Mississippi native called to ministry by a small Baptist church at the age of sixteen. After serving in World War II and procuring a degree from Yale Divinity School on the G.I. Bill, Campbell took a job as chaplain at the University of Mississippi in the fifties, before senior administrators forced him out for playing ping-pong with an African American minister.

He counseled and supported Freedom Riders in the sixties, ministered to imprisoned Klansmen in the seventies, and travelled with Waylon Jennings as a cook in the eighties.

From there, he worked in the race relations department of the National Council of Churches, moving to Nashville and beginning to appear, Forrest Gump–like, in one sacred scene after another. He can be seen in a photograph ushering the Little Rock Nine past an angry white mob in 1957. He met John Lewis at a training session in nonviolent resistance at the Highlander Folk School. He counseled and supported Freedom Riders in the sixties, ministered to imprisoned Klansmen in the seventies, and travelled with Waylon Jennings as a cook in the eighties. (“I was the one that opened and closed the microwave the most.”) No role was too small or too large to escape Campbell’s self-deprecating vocational assessment: “I don’t like the term ministry…It’s arrogant, presumptuous, even imperialistic.”

While his obituary did appear on the front page of the New York Times in 2013, he did not conduct himself in the manner of a legendary historical figure. He looked after and loved the distinctly unfamous, the marginalized, the estranged, and the incarcerated. He steadfastly refused to credit any hierarchy or system that placed one person higher (or lower) than anyone else. As a relentlessly witty and intensely articulate opponent of discrimination and an aggressive ambassador of reconciliation, he never met a snob he wasn’t hell-bent on delivering from snobbery. How does one live a life so extraordinarily varied and so inspiringly defiant?

By asking around, I discovered that Campbell was in the phonebook and entirely accessible to anyone who wanted to discuss such questions, especially if it involved taking him out for barbecue. In 2003, with the prompting and encouragement of a friend and local minister, David Harkness, we made the trek to his farm in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, to behold the man. Through Campbell, I began to understand better the neighbors and strangers of Nashville.

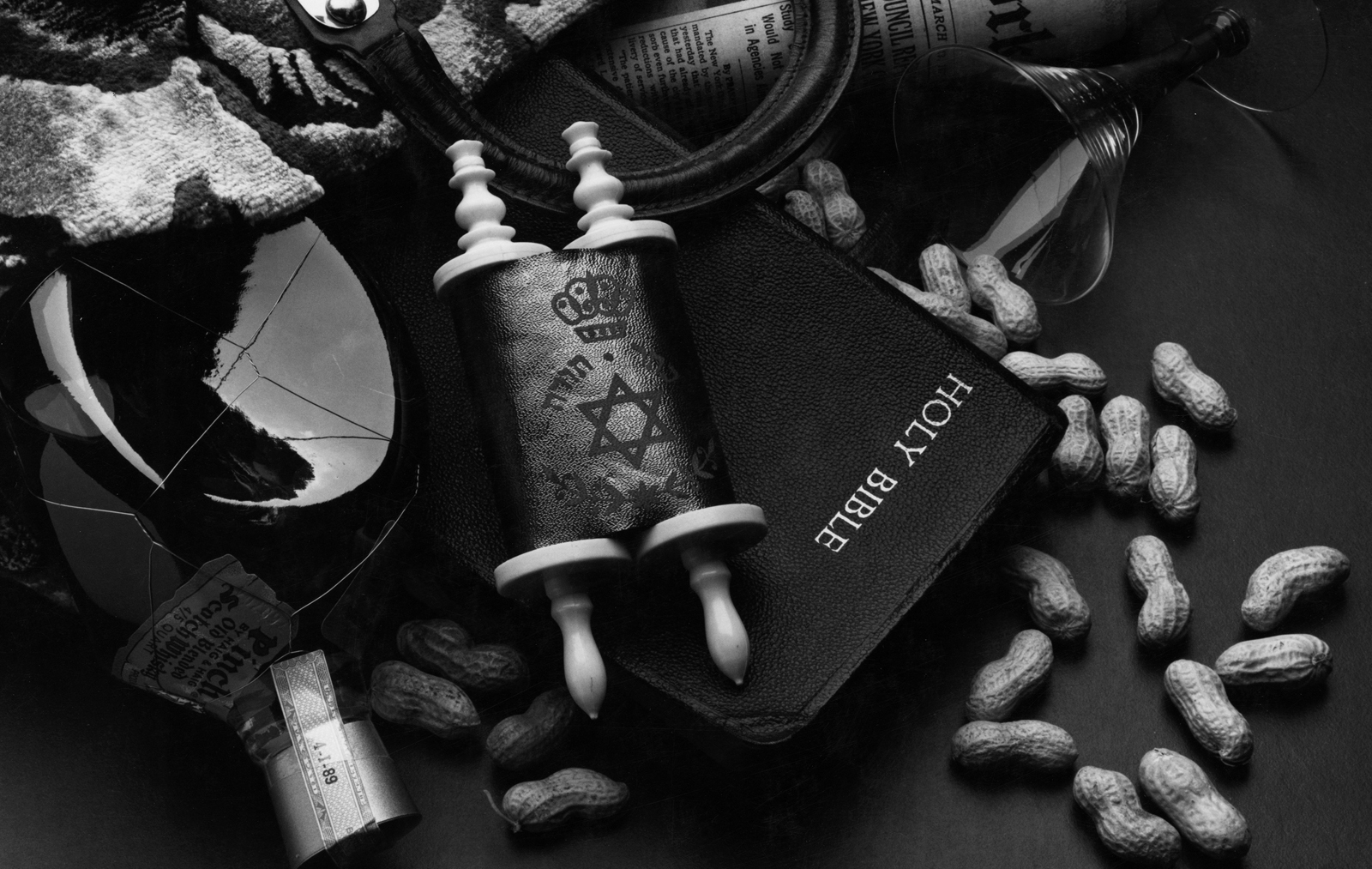

Campbell often held court at Gass’s Tavern, a beer hall down the road from his Mt. Juliet home. He called the joint his church. It served as a reminder that sacred work can be done well when human beings come together at table, trying to hear one another over the hum of an air conditioner.

Despite his infamy in some circles, he was an insistently hospitable introvert possessed and haunted by a devastatingly revolutionary idea: Katallagete, a Greek word he picked up from the Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to the community of Corinth. It means “Be ye reconciled” to one another in view of God’s mercy. Or, as Campbell liked to translate it, Be who you are. To respond to such an imperative is a life’s work, best undertaken together with others. And we’re probably never more ourselves than we are when we’re eating. When we satisfy our hunger, it’s harder to maintain a front. We surrender our composure and, out of the necessity of chewing, we enjoy these amazing seconds of silence. Words come to mind and get spoken. We have no choice but to be patient and listen.

Receiving visitors and paying visits, Campbell would offer watermelon or cornbread unto all manner of human being. There could be a loss to be grieved, an apology to be made, or a realization to be had, but blessedly, a pickled egg is not an argument or even an assertion. It’s just an offering that can, like any true gift, bring a person out of hiding. Campbell carried with him, in a kind of deep conjuring, a space in which to be oneself.

He brought the same largely unsanctioned ministry to those among us who feel estranged from institutionalized religion. He liked to say that you can’t go to church, you just have to be it, together with others. Church, for Campbell, had to be a verb. He told me about a neighbor who’d drop by and steer the conversation toward his anxiety over never having been baptized. After the third or fourth telling, Campbell excused himself and crept quietly back into the room, sneaking up behind him with a bowl of water. Before the visitor could turn around, Campbell blurted the words, “I baptize you in the name of the Father…” and performed the rite. This was anything but flippant. Campbell took the love of God seriously. Be ye reconciled. Act like it.

As much as he reveled in telling these stories, he also understood that you have to do without saying. Nashville, at its Campbellite core, gets this. The city knows all too well the toxicity of empty moralizing. After all, televangelism is one of our largest industries. Campbell called such agents of false witness “electric soul molesters.” That culture of fakeness can make the real deal of community, of neighborliness and down-home hopefulness, all the more hard-won. The dishes we come to think of as comfort food have gained this association through healing and humble gestures. Friends and neighbors communicate deep affection, one squash casserole at a time.

Here’s Campbell on this sacred ritual in his 1977 book, Brother to a Dragonfly:

Somehow in rural Southern culture, food is always the first thought of neighbors when there is trouble. That is something they can do and not feel uncomfortable. It is something they do not have to explain or discuss or feel self-conscious about. “Here, I brought you some fresh eggs for your breakfast. And here’s a cake. And some potato salad.” It means, “I love you. And I am sorry for what you are going through and I will share as much of your burden as I can.” And maybe potato salad is a better way of saying it.

To be true to Will Campbell’s witness is to take stock of all the ways Nashville has resisted and even persecuted the call to humanness, the radical spirituality undertaken within its environs. There is no deep reconciliation apart from deep reckoning.

I think of John Lewis, who worked closely with Campbell while living in Nashville as a student at American Baptist College. Proclaiming God’s desegregated future in 1960, he and fellow student James Bevel demanded the right to order and eat a hamburger in peace at a downtown Krystal. The manager locked the two of them in the restaurant and turned on a fumigator full of insecticide.

“I didn’t panic. I was frightened, but I wasn’t frantic,” Lewis recounts in his memoir, Walking With the Wind. As the room filled with fumes, the young men could no longer see each other. Bevel started loudly quoting the Book of Daniel: “Whoever falleth not down and worshipeth shall the same hour be cast into the midst of a burning fiery furnace.” At last, firemen burst through the front door.

Lewis and Bevel had both trained with another Will Campbell acolyte, the Reverend James Lawson, for moments like these in which they’d face hostile crowds and inevitable arrest while sitting in the “whites-only” sections of downtown Nashville restaurants. One Saturday, Lawson was on the scene to coach students and to dissuade white passers-by from responding violently to young people whole-heartedly—and whole-bodily—committed to nonviolent witness. Lawson approached one aggressor in a motorcycle jacket at the center of a group who’d kicked Bernard Lafayette and Solomon Gort. The man directed a racial slur at Lawson before spitting in his face.

Reverend Lawson regarded the aggressor calmly and asked if he might have a handkerchief. The man was so taken off guard that he’d handed it to Lawson before he knew what he was doing. As Lawson thanked him and wiped his face, he asked the man if a nearby motorcycle belonged to him. It did. And in no time, they were discussing horsepower. Within a few minutes, the man was asking how he could aid Lawson and the students in their work. The script had been flipped. I once asked Lawson how one might develop the habit of handling people so beautifully, and he responded, as if it was just then occurring to him, “You have to keep in your mind an imagery of infinite possibility.”

“You have to keep in your mind an imagery of infinite possibility.”

These words serve as a proverb for living up to your most lyrical, imaginative, and loving self. I think them worthy of a tattoo. Hear them again: “You have to keep in your mind an imagery of infinite possibility.” Try that. And when I think of that summons, I think of Will Campbell, whose funeral Lawson officiated. Both men represent the habits of mind and body they referred to as Beloved Community, a way of relating that can serve, every so often, as the unhidden conscience of a city.

Campbell cared for those who hurt and didn’t pass judgment on why they hurt. In 2003, he went to visit a seventy-three-year-old friend who was incarcerated in Kentucky. After driving more than three hours from Nashville, Campbell and a carful of friends, including John Egerton, arrived at checkpoint and prepared to go through security. A young male guard pointed out that one member of their party, wearing sandals, had failed to comply with the footwear standard for inmate visitation. When Campbell wondered aloud if it might be possible to make an exception, the guard yelled, “One more word out of you and none of you see anyone here today!”

The group retreated to the parking lot, where Will broke down in tears. After a trip into a nearby town to buy some shoes, they were allowed in.

“What do you do?” Campbell asked me later, having laid out the situation. He fixed both eyes on mine in an unexpectedly plaintive stare. He could tell I was thinking about the visit, the drive, and how they might get in, but he had a larger and more immediate vision in mind. “What do you do with him?”

It would not occur to many people to extend any degree of concern to the angry young guard. Most, in fact, would be ready to pounce. A lifetime of persistent work in and around prison culture had not hardened Will Campbell to the outburst.

The standard of humanness he held up to all who knew him was the unending call to meet fear with communion rather than hostility.

Weeks later, he was still mourning it and wondering how he might have more righteously engaged that sad soul, enmeshed—like we all are—in an endlessly adversarial culture. I’d read him and admired him from afar, but it was in this moment that I felt challenged and invited into a long wondering over the suffering of our world. The standard of humanness he held up to all who knew him was the unending call to meet fear with communion rather than hostility.

Campbell saw Lawson’s “imagery of infinite possibility” everywhere and viewed it as an imperative. Every human being he met was a bearer of the divine image. He refused to think of people according to stereotypes, categories, or labels. Once, I asked him, “Shouldn’t the pouring out of God’s spirit on all flesh on Pentecost have settled the race issue once and for all?”

“It did!” he fired back, looking at me with bewilderment and concern as if I was choking on a seed. And I realized I’d been out-conservatived, out-liberaled, and out-evangelicaled. For Campbell, Pentecost was a settled reality, and we’d all do well to act like it. Be yourselves. Be ye reconciled.

Campbell was present in 1998 when Sam Bowers, White Knight of the Ku Klux Klan, was sentenced to life for the murder of civil rights hero Vernon Dahmer. Campbell greeted Bowers warmly just before taking a seat in a Hattiesburg, Mississippi, courtroom with the Dahmer family. When a reporter asked how he could befriend both parties, he said, “I guess it’s because I’m a goddamn Christian.”

To risk an understatement, this radical hospitality is not widely publicized today. But from where I’m standing as a child of Nashville, the Campbellite spirit is in our blood, even when we’re ignoring it. We’re a space of unlikely reconciliation, of contrary forces hopefully somehow working it out, one potato salad at a time. Keeping in our minds, so help us God, an imagery of infinite possibility.

David Dark is a theologian and author who teaches at the Tennessee Prison for Women and at Belmont University. He delivered a version of this article as a talk at the 2016 Summer Foodways Symposium in Nashville. All images courtesy the McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi.

Encore: Nashville Today

Just off Nolensville Pike on the southern outskirts of Nashville lies Little Kurdistan — a thriving community of Kurdish immigrants and new generations of Kurdish-Americans. Watch “Little Kurdistan” by Ava Lowrey.