Albany Civil Rights Movement Newsreels from Southern Foodways on Vimeo.

Rosalind Bentley, the reporter of last week’s podcast episode, found some extra Gravy for us. The old newsreel footage is courtesy of the University of Georgia’s WSB Newsfilm Collection. See the end of this post for a description of what you’re seeing.

By Rosalind Bentley

My cousin, Clennon King, sent me an email a few hours after the “Hostesses of the Movement” podcast went live.

The subject line read: “Aunt Lucille Footage.”

The body of the email was just a link. I clicked on it. Then my eyes welled.

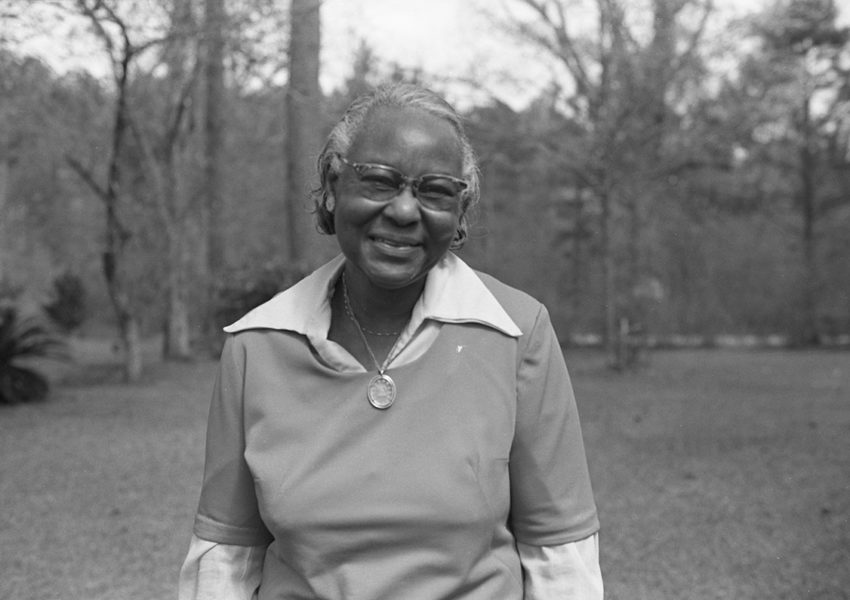

There she was, Aunt Lucy, a woman who’d provided food and sanctuary to Dr. Martin Luther King, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and other strategists of the modern Civil Rights Movement in Albany, Georgia. She was gliding, as she always seemed to do when she walked. To the right of the screen was Clennon’s mother, Carol King. The men behind them were King’s and Abernathy’s attorneys, Donald Hollowell and C.B. King. C.B., my cousin and no relation to Dr. King, is Clennon’s father and Aunt Carol’s husband. They were all walking past shiny parked cars, and they were about to enter a courtroom on Pine Avenue in Albany.

The old newsreel footage is courtesy of the University of Georgia’s WSB Newsfilm Collection. Clennon, who makes documentaries, discovered the video while researching a new project. The compilation of clips captures the group in July 1962 just before District Judge J. Robert Elliot issued an injunction against King and Abernathy leading mass demonstrations against segregation in Albany. The injunction was vacated days later by Atlanta Appellate Court Judge Elbert Tuttle.

Aunt Lucy was only on screen for seconds, but what struck me was her ease, her confidence. She looks away from the camera as she realizes that she is being filmed, but not too quickly. There she is, in the middle of history, an active participant. Eager. In her short-sleeved summer suit, crisp and looking “smart,” as she liked to put it when you looked good. She was headed for the gallery.

Privately, she’d cooked for the defendants and housed the attorneys. That was her main contribution to the movement, an essential one. But on this day, she was going to be in the center of change, publicly.

I’ve replayed the video several times. In Aunt Lucy’s face, I see the features of my other great aunts and my grandmother, who was Aunt Lucy’s oldest sister. All of them are gone now. I see my cousin Brenda, Aunt Lucy’s daughter, who, along with Clennon, helped me tell Aunt Lucy’s story. I also saw a woman who found a way to fight.

Lucille Leslie Burton went to court that day, but I have little doubt that after the hearing was over, everyone gathered at her house. I imagine she would have served iced tea, maybe cold roasted chicken for sandwiches, the crusts cut away from the white bread and the corners pointed on each slice. Maybe tomato aspic studded with stuffed olives was on the side. And there would have been lemon ice-box cookies for dessert.

Then, based on all I’ve learned while researching this podcast, she probably joined in the conversation of what the next move should be. The marches against Jim Crow would have to continue. They just had to figure out how.

****

“Aunt Lucy” Video Breakdown

July, 1962

King’s and Abernathy’s attorneys walking into a courtroom.

Mass meeting at Shiloh Baptist Church

Rev. Wyatt T. Walker, civil rights leader and SCLC leader, pins black arm bands on Coretta Scott King and Juanita Abernathy, who were in Albany to protest the injunction against protest marches.

Spectators in Albany gathering outside city hall.

Police Chief Laurie Pritchett and unidentified man outside city hall.

Coretta Scott King

Rev. Wyatt T. Walker preaching at a mass meeting.

Laurie Pritchett among spectators

Aunt Lucy and Aunt Carol King about to enter court on Pine Street. To the right of Aunt Carol on the screen in her husband, C.B. King, attorney for King and Abernathy. The man in the hat is attorney Donald Hollowell, who won the case that integrated the University of Georgia. Hollowell was also one of the lead attorneys.