The Georgia Peach in Black and White Civil rights in the shadow of Georgia’s signature crop

by Tom Okie (Gravy, Winter 2015)

My father’s 1967 Volvo 122 smells like dust. Pulverized foam from the ceiling and seats, dried sweat from a thousand entrances and exits on summer days, sulfur and fuzz and road dirt from the orchards. The engine putters. The windows are open, and the triangular vents shunt hot, exhaust-laden wind into our faces. We are on the way to the Station.

Out of the neighborhood, past the house with a balcony and an elderly African American gentleman in his wheelchair; up through the rural north end of Houston County, past the Dunbar place, more than a century old; into Peach County, past barbed-wire fences penning in dirty white cattle, past trailer parks and the ruined speedway; around the outer edges of the Station, past the thick loblolly pines and tall chain-link fencing that keeps trespassers out and pesticides in.

Here we are. The USDA Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Station. Down the long drive, rows of young pecans on the right, aging greenhouses on the left, we arrive at the main building, a two-story brick-and-metal structure, thoroughly unremarkable in that institutional style of the 1960s. Inside, several laboratories and a cold room make up the building’s core, encircled by a hallway and offices. Blanketing one wall are plaques with 8×10 photographs of the station’s scientists, all weathered faces and windblown hair, thick glasses and plaid shirts, one impressive mustache, two throat-length beards: the unfashionable fashion of the late-twentieth-century agricultural scientist.

I was born into this world just as my parents, fresh out of graduate school, bought their first home in middle Georgia. Thirty-two years later, as I finished up my own Ph.D., my father retired. I watered seedlings in the greenhouses, thinned young peaches with a plastic baseball bat, emasculated flowers during pollination season, helped type the book that was the key scholarly contribution of my father’s career, spent a summer testing mashed peach leaves for plum pox virus. The Station was a key orientation point of my childhood, a fixture of the landscape as taken-for-granted as the country roads that led us there.

Something—someone—nags at my memory. The black man in his wheelchair, waving at passersby. He was there almost every day. Before his stroke, my mother once told me, he had been a civil rights leader. Civil rights? In my young mind, this was something that happened in other places, on a national stage. What kind of civil rights movement could have occurred in middle Georgia?

Tax records peg Oscar C. Thomie, Jr. as a former owner of that house with the balcony, and a search for his name yields two leads. The first is that Thomie was the president of the Houston County NAACP in the 1960s. Under his leadership, the chapter filed a suit against the Houston County Board of Education that led to a 1969 court order to integrate—an order that was still in place forty years later, much to the consternation of those who wished to redistrict the schools. A few months later, in May 1970, Thomie led 430 black protesters in a desegregation demonstration in Perry, the county seat, and was arrested. According to a telegram smuggled out of the prison from Thomie and the other leaders, state troopers resorted to tear gas and beatings to subdue the demonstrators, and then packed them “like sardines” into schoolbuses for a twenty-mile trip to a condemned prison camp that Governor Maddox had deemed “unfit for a prison.”

The second lead directs me to the Oscar Thomie Homes, a seventy-unit public housing community in north Houston County that became a half-vacant eyesore. One of eight housing projects in the city of Warner Robins, the Thomie community was built in 1964 and neglected for decades. Pointing to the broken sidewalks, peeling paint, rusting pipes, the director of the housing authority told a reporter in 2012, “I really don’t know what we can do to turn this around. Renovation would cost $11 million, demolition only $500,000.”

A few miles from my neighborhood, this housing project fell into disrepair. A few houses up the street from my own, a local hero did the same, watching in involuntary silence as his neighbors went about their lives. Thomie died in 1994; the homes were razed in February 2015.

The Station was real to me, solid, permanent; the local civil rights movement was, like Mr. Thomie himself, something of a ghost. But this contrast was illusory. The Station was just as contingent as any other piece of the institutional and built environment. The groundbreaking in 1969 followed twenty years of advocacy and argument, approvals and administrative suspensions. Thomie’s desegregation victory and subsequent jailing, however ghostly to me, followed a long and determined campaign. Indeed, the comparison is on one level patently absurd. One campaign protested the poor health of the state’s peach trees; the other the legal oppression of 1.2 million of the state’s people.

The Station was real to me, solid, permanent; the local civil rights movement was, like Mr. Thomie himself, something of a ghost. But this contrast was illusory. The Station was just as contingent as any other piece of the institutional and built environment. The groundbreaking in 1969 followed twenty years of advocacy and argument, approvals and administrative suspensions. Thomie’s desegregation victory and subsequent jailing, however ghostly to me, followed a long and determined campaign. Indeed, the comparison is on one level patently absurd. One campaign protested the poor health of the state’s peach trees; the other the legal oppression of 1.2 million of the state’s people.

To compare would cast these stories as parallel lines, which, as we know from grade-school geometry, never intersect. In the 1890s, Fort Valley whites had their peach orchards; blacks their industrial school, now called Fort Valley State University. In the 1920s, whites held their Peach Blossom Festivals to prove the worthiness of their enterprise. Blacks staged their Ham and Egg festivals to prove the worthiness of rural self-sufficiency. In the 1960s, whites campaigned for an expanded peach lab, and blacks rallied for voter registration and city elections. This parallelism holds true in the archival record. The underfunded and scattered special collections at FVSU and the better-situated Atlanta University Center archives tell the black story. Newspapers, the papers of Senator Richard B. Russell, and records of congressional proceedings tell the white story.

There was nothing inevitable about the Station. Peach growers and their allies campaigned for it; Senator Richard B. Russell Jr. secured the funding; and scientists moved into it to do their work. How they did so reveals much about modern agrarianism at a historical moment not concerned with the countryside.

There was nothing inevitable about the Station. Peach growers and their allies campaigned for it; Senator Richard B. Russell Jr. secured the funding; and scientists moved into it to do their work. How they did so reveals much about modern agrarianism at a historical moment not concerned with the countryside.

The white civic leaders in Fort Valley, the county seat of Peach County, had been loyal supporters of Senator Russell for almost his entire public career. As a young leader in the state house of representatives, Russell had played a key role in pushing through the new county proposal in 1924. The county went his way for the governorship in 1930, and for the U.S. Senate two years later. In that race, he faced U.S. Representative Charles Crisp of Americus, who had two decades of national political experience and endorsements from most of the state’s major newspapers. The younger Russell won resoundingly, and his supporters around Fort Valley made Peach County an island for Russell in a middle Georgia sea of Crisp votes.

Russell, then, was a powerful man with a soft spot for the peach growers, their place, and their signature commodity. To make their case for more federal support in the 1950s, the growers used the same language with which they had celebrated the Georgia peach industry since the 1880s. Peaches, to them, were a more sophisticated alternative to cotton. The people of the “land of cotton,” they wrote in 1950, had “learned from bitter experience that they can not live on cotton alone.” They needed better varieties of fruits, berries, and nuts, for “marketing in the north before northern crops are ready” and to “round out the diets of the people of the new Southland.” These would include improved peaches, of course, and also Satsuma oranges, persimmons, feijoas, loquots, sapotes, avocados, olives, jujubes, bush cherries, dewberries, pistachios, and quinces—to name just a few of the thirty-four fruits and nuts they offered for consideration. If the proposal seemed outlandish, Russell did not let on, and he promised to take it up with Secretary of Agriculture Charles Brannan.

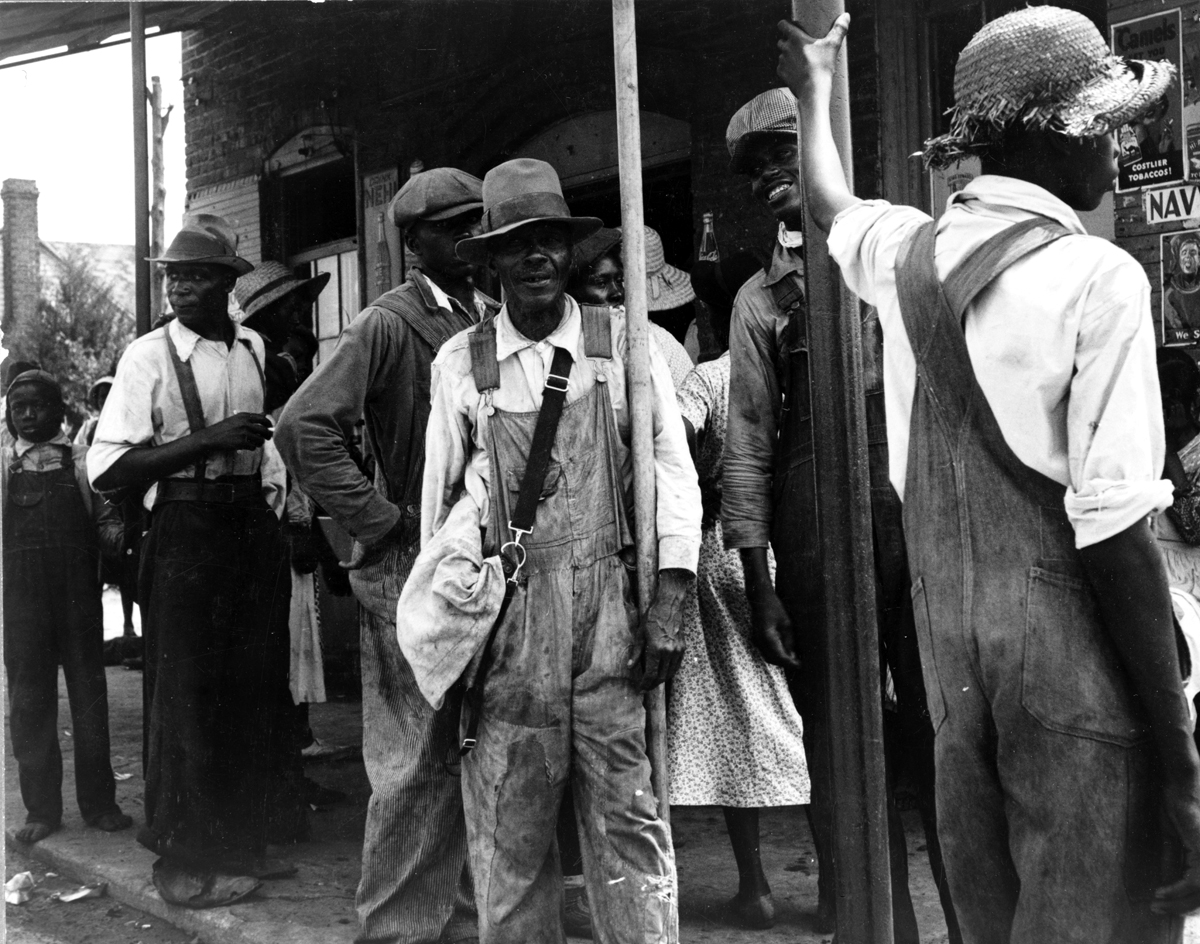

Twelve years later, the growers appeared before the Senate Subcommittee on Agricultural Appropriations, which Russell chaired. They brought along a mimeographed proposal and poignant photographs of bacteria-spotted fruit and stricken peach trees. “Why did these trees die? What can we do to prevent this loss?” they asked. “We need research to find the answers.” The future of the industry was at stake, the growers said, and its demise would eliminate an essential fruit (rich in vitamin A and only thirty-five calories!) from the nation’s diet. It would also send shock waves across the economy of the rural South. Banks would fire their agricultural finance specialists, small-town druggists would close up shop, manufacturers of pesticides and equipment would reconfigure their business or fail, freight carriers would be deprived of an enormous summer business. Intriguingly, the proposal also urged Congress to remember “the plight” of the rural labor force. With cotton and corn production mechanized, the peach industry was the only thing standing between these rural Southerners and either migration to the North or West or “the already crowded offices of our welfare agencies.”

The hearing itself was not much of a grilling. At several points, Russell helped the cause along with his own interjections. “When it comes to eating fruit, man has never yet developed anything which has as exquisite and delightful flavor as a tree-ripened Elberta peach,” he declared.

In another exchange, Senator Milton Young (R-North Dakota) agreed that there was a “great need” for research into the pests and diseases that threatened the industry. Then, in what seemed to be a complete non sequitur, he said, “I have been down in Georgia two or three times, but never during the summer. I would like to do that sometime.” Russell joined him in reverie: “It is very beautiful. I would be glad to have you come down and see the peach trees when they are in bloom. There is no more beautiful sight than a peach orchard in full bloom.”

The fact that peach trees bloom in spring, not summer, underscores the point: It was the fruit’s aesthetic quality, its cultural importance, that moved Russell. The proposal passed the Senate subcommittee and, after what Russell later described as the most difficult negotiations in his thirty years as chair, the House as well. Congress authorized $500,000 for planning and construction of the lab. Letters and telegrams of thanks poured into Russell’s office, like this one from Georgia Peach Council president Edgar Duke: “I am amazed that you so willingly devoted your personal attention to our request, despite the extremely heavy demands being made on you by what, I must admit, are far more serious and important issues. I will never forget…that except for your active support and hard work, our cause was lost.”

As Duke had intimated, Senator Russell had other things on his plate. Two weeks earlier, James Meredith had registered for classes at the University of Mississippi—after an all-night battle between segregationist protestors and federal marshals that left two dead and over 300 wounded. Russell had publicly and angrily protested the use of federal troops to guard Meredith. Despite his best efforts to “fight these outrageous measures with all the power of my being”—civil rights legislation moved forward. The Russell-led Southern bloc in the Senate, which had stymied civil rights reform since 1957, was broken.

As Duke had intimated, Senator Russell had other things on his plate. Two weeks earlier, James Meredith had registered for classes at the University of Mississippi—after an all-night battle between segregationist protestors and federal marshals that left two dead and over 300 wounded. Russell had publicly and angrily protested the use of federal troops to guard Meredith. Despite his best efforts to “fight these outrageous measures with all the power of my being”—civil rights legislation moved forward. The Russell-led Southern bloc in the Senate, which had stymied civil rights reform since 1957, was broken.

Legislators, then as now, deal with a bewildering array of issues in short succession, and many finish their careers with uneven voting records. Blocking civil rights legislation and shoring up Southern agriculture may seem unrelated, just another example of senatorial schizophrenia. But I think there’s a connection. A clue emerges from a close reading of the 1962 hearing, as the growers made their case. While their proposal offered a long list of economic ramifications of the peach industry’s decline, the testimony centered on just one. As Edgar Duke put it, “Practically every other farming operation in the South is now or shortly will be mechanized, so our unskilled farm labor must depend almost entirely on the growing and harvest season of fruit and nut crops for its livelihood.” Save the peach industry, in other words, and you provide a livelihood, however precarious, for the region’s unskilled farm labor, keeping them out of the “welfare agencies.” Although Duke was careful not to say so outright, in a region where 30 to 60 percent of blacks lived in poverty, and where 10 to 25 percent worked in agriculture, “unskilled farm labor” meant black folks.

Meanwhile, the black residents of Peach County were on the cusp of their own movement. Angered by the 1963 murder of a black inmate , local African Americans organized the Citizenship Education Commission (CEC). Almost simultaneously, probably in response to the wave of sit-ins and other direct action campaigns across the South, Fort Valley’s white leadership called for a formal “racial commission,” to which the mayor appointed four whites and four blacks. The many examples of civil disobedience throughout the South, along with a CEC-led “Don’t Shop Where You Can’t Work” boycott, lit a fire under the commission. Colored and white signs above water fountains began to disappear. Certain blacks ate in white restaurants. More worked in white-owned businesses and earned promotions.

Overt activism was new in Peach County. Prior to 1963, the path to black empowerment had been thoroughly (Booker T.) Washingtonian, led by the black administration and faculty of Fort Valley High and Industrial School. Just a few years after the school’s founding in 1895, principal James Torbert proclaimed, “The negro ought to remain in the rural districts and buy land, improve it, cultivate it, and make country life more attractive, healthy and prosperous.”

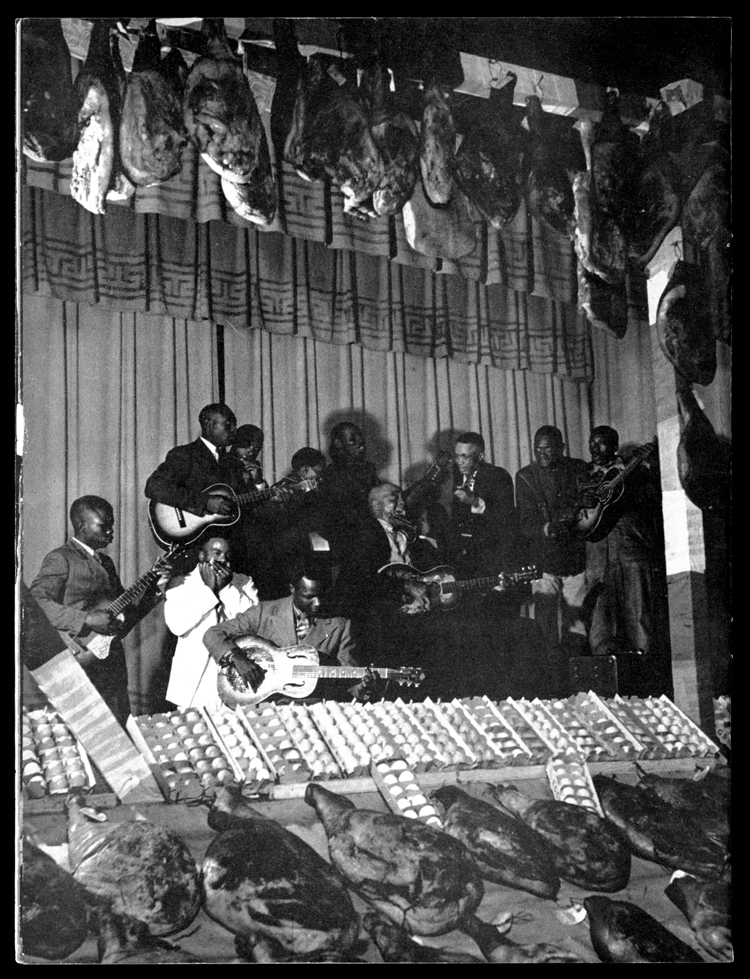

Thirty years on, school president Henry A. Hunt wrote much the same thing: “Negro farmers must be led to see for themselves that it is best to remain on the farm instead of having the information given to them by bitter experience in the crowded cities.” In 1916 extension agent and faculty member Otis O’Neal began an annual Ham and Egg Show, a forum for black farmers to exhibit their best pork and poultry products for cash prizes. By the 1950s, it had become a nationally-recognized blues festival as well as a platform for O’Neal to “pound away” at the “importance of farmers staying on their land instead of throwing down the plow” for urban jobs.

This rural development message had subversive potential. Whose land were these black farmers going to purchase and own, after all? Still, it was popular among whites—at least in the abstract. When it got down to specifics, there were problems. In 1936 Rexford Tugwell’s Resettlement Administration (part of a relief bill that Russell had helped to sponsor) optioned several thousand acres in Peach County for a proposed Fort Valley Farms, a cooperative project of about seventy black families. Peach growers and their allies sent an urgent telegram to Tugwell. “Before proceeding further with your resettlement project in Fort Valley,” they wrote, “we earnestly request that you investigate the feeling of the citizens of Peach County in regard to same. You will find serious and strong opposition.” The project found a slightly more receptive audience in neighboring Macon County as Flint River Farms and flourished for the next two decades. In the 1950s, black extension agent Robert Church decided to get into peaches as an experiment in diversification, but he found no packing shed who would pack his crop. As these reactions suggest, when black Southerners talked about the importance of staying on the farms, white Southerners imagined them staying on white farms, as low-wage labor.

From 1963 until 1980, Peach County blacks fought for better electoral representation. The first black candidate ran for city council in 1964. The CEC used funding from the Voter Education Project to run regular registration drives from 1965 through 1972. They had good prospects of success. Out of twenty-three majority African American counties in Georgia, Peach County blacks had the lowest poverty rate, the highest median income, the highest rate of high school graduates, and the second highest rate of black economic independence. By 1976 nearly 48 percent of registered voters were black; Fort Valley elected Rudolph Carson as its first black mayor in 1980.

These efforts were hampered, though, by external pressure and internal discord. In 1972, Fort Valley whites filed a suit against Fort Valley State College for racial discrimination, arguing, incredibly, that Fort Valley’s whites had been “substantially disenfranchised” by all the voter registration activism emerging from the college, and that the institution should be desegregated just like the rest of the University System (only 15 of the institution’s 2,300 students were white). Meanwhile, Carson’s election exposed a broader division within Fort Valley’s black community between the original mission of the college to develop the rural African American community without overtly challenging white supremacy and the more activist approach of college and city leaders since the 1960s. Carson tried unsuccessfully to finesse this division. After his first year in office, he gave an interview to the local paper in which he appeared to disavow any connection to the black community. He did not want Fort Valley to become a black town, he said, nor did he want to be known as a black mayor.

In response, both blacks and whites staged major registration drives in 1984, with nearly 40 percent more voters registered than in 1980. But 90 percent of white voters turned out, compared with only 60 percent of black voters. Carson lost. His fear that Fort Valley would become a black town, however ill-advised, was well-founded. As of 2014, Fort Valley’s population is only 13.6 percent white, compared to Peach County as a whole (51.5 percent), and the northern end of the county around Byron (~70 percent).

The Station stands in white Peach County. The original research lab, first used by federal scientists around the turn of the century, was a small facility in Fort Valley. Researchers used growers’ fields to conduct most of their experiments. The current laboratory is a remodeled Navy installation, adjacent to Interstate 75, with 1,100 acres at its disposal. There is a curious synchrony between the movement of federal research in middle Georgia and the movement of Peach County’s white population.

When my parents moved to middle Georgia, they wanted to live near my father’s workplace. Fort Valley seemed too “Old South,” Dad says. Houston County had better schools, and the city of Warner Robins, home to a large Air Force base, was friendly to newcomers. So I grew up oblivious to the struggles for equality and the campaigns for rural livelihood that defined middle Georgia life for the last century and a half. Only in the last eight years of research into the history of the Georgia peach have I begun to come to terms with the inconvenient, harder edges of this local history.

The Georgia peach is an icon, serving as shorthand for Southern beauty, hospitality, sweetness, and agrarian identity. But its roots sink deep into the messy racial politics of Southern history, and as much as some of us have forgotten all but the high points of that history, we need to hear it again in all the fear, anger, sorrow, and joy of the original experience. So that even our clichés, fuzz and all, carry some truth in the aftertaste.

Tom Okie is an assistant professor of History and History Education at Kennesaw State University, where he teaches courses in American and food history and mentors future secondary social studies teachers. His book, The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South will be published by Cambridge University Press in 2016.

Tom Okie is an assistant professor of History and History Education at Kennesaw State University, where he teaches courses in American and food history and mentors future secondary social studies teachers. His book, The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South will be published by Cambridge University Press in 2016.

Images: (Header) Photo by Jamey Guy; (Full-width peach blossom and hanging peaches) Photos by Kate Medley; All peach crate labels courtesy of the University of Georgia Extension Service.