A MEAL AT DELLA'S PLACE Local foodways and entrepreneurship at a Raleigh boardinghouse

by Elizabeth Engelhardt (Gravy, Winter 2016)

We live in messy, in-between spaces.

Take the Southern boardinghouse from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. The women (and some men) running Southern boardinghouses lived in cities and small towns, near remote vacation spots and railroad-accessible resorts, temporary logging or railroad camps, and more permanent factories. They clustered around schools, courthouses, and business centers. Some keepers called themselves businesspeople; others insisted they were just helping out extended family or friends. Lines blurred between boardinghouses and hotels, and also between restaurants, brothels, cafés, taverns, resorts, and private homes. Owners, proprietors, and customers negotiated the uses of these flexible food spaces.

![]()

The food was diverse, too. Ingredients for the boardinghouse table were grown in the backyard or processed in distant factories, prepared simply or in complicated dishes. Cooks chased culinary fashion or remained tried and true. Boardinghouses, and their foods, evaded easy definition. They were spaces of transition and becoming, not quite one thing and not quite another. One academic word for that is “liminal.” Liminal spaces are ones in which definitions are in flux, new ways of being are tried out, and powerful transitions emerge. That is the wonder and usefulness of boardinghouses to the Southern food story.

The food was diverse, too. Ingredients for the boardinghouse table were grown in the backyard or processed in distant factories, prepared simply or in complicated dishes. Cooks chased culinary fashion or remained tried and true. Boardinghouses, and their foods, evaded easy definition. They were spaces of transition and becoming, not quite one thing and not quite another. One academic word for that is “liminal.” Liminal spaces are ones in which definitions are in flux, new ways of being are tried out, and powerful transitions emerge. That is the wonder and usefulness of boardinghouses to the Southern food story.

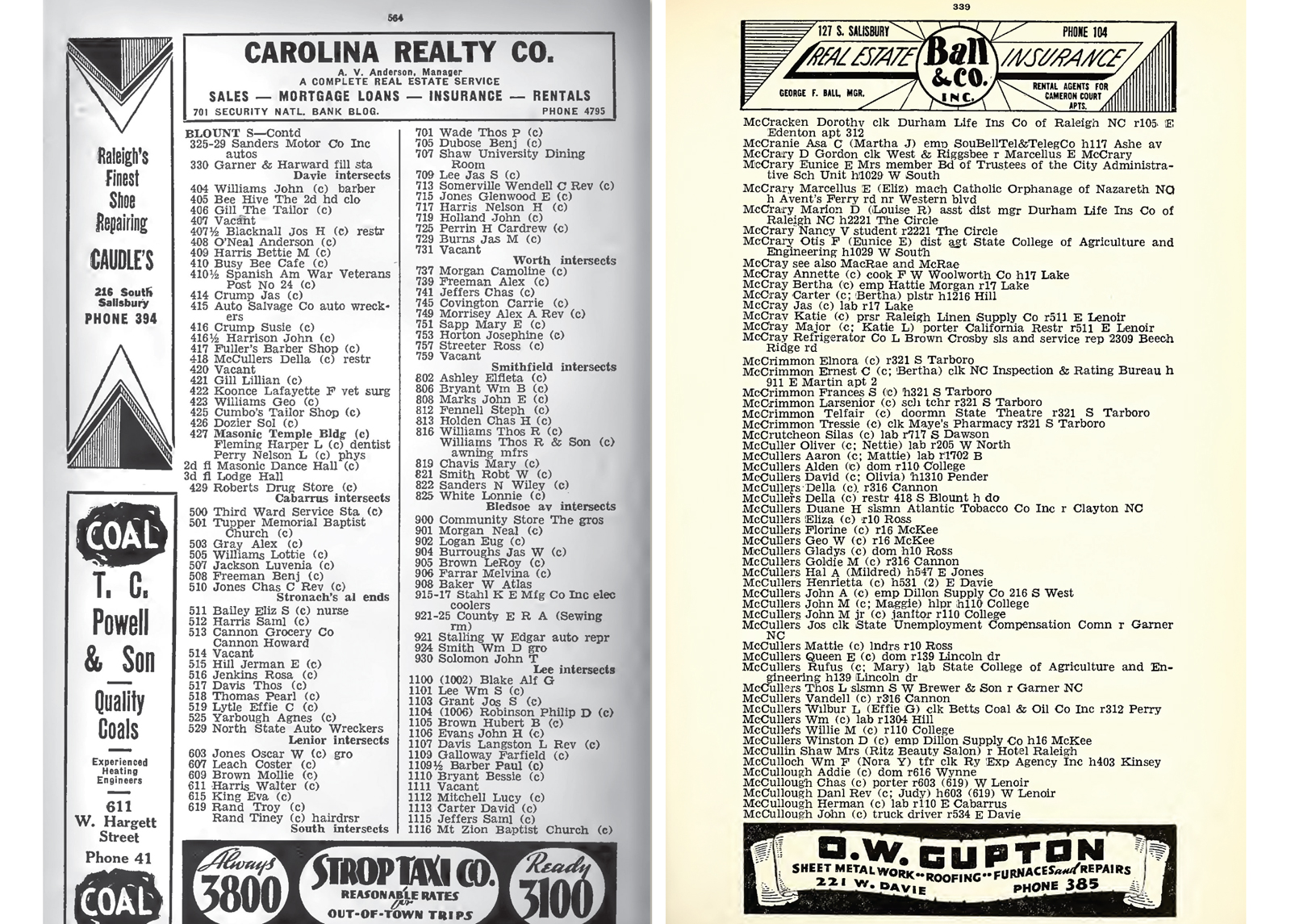

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal arts programs, sought to capture a portrait of everyday life in the United States in the 1930s. With that goal in mind, it is no wonder that boardinghouse keepers, lodgers, and diners emerge frequently in the FWP’s papers and transcripts. In 1939, Della McCullers of Raleigh, North Carolina, told her boardinghouse story to FWP documentarian Robert O. King. McCullers ran a restaurant and gathering space she called a boardinghouse. The few beds she kept were mostly occupied by extended family. McCullers’ primary business was food. She served meals for working folks in the heart of Raleigh’s African American business district.

Located in the 400 block of S. Blount Street, “Aunt” Della’s place, as the establishment was called, was mere blocks away from Shaw University, the first historically black institute of higher education in the South. In the 1930s, residents of the neighborhood could fulfill all of their needs on Blount Street or nearby Hargett Street. There were general stores and gas stations, churches and beauty parlors, doctors’ offices and a drug store. McCullers was born in the neighborhood in 1874, married in 1911, and widowed in 1916. When King interviewed her for the FWP, she was sixty-four years old. Before opening Della’s, she had taken in laundry, cooked in private homes, operated a café, and managed a hotel.

Over the course of her adult life, McCullers successfully shifted careers and adapted her business strategies according to new technologies, changing economic conditions, and the needs of her employers and customers, both black and white. Born Della Harris, she learned how to wash and iron as a girl. Later, she learned to cook while working in the home of a white Raleigh family. After her husband, John McCullers, a brickmason, passed away, McCullers returned to the workforce to support her three young children.

The introduction of household appliances and automated commercial laundries drove McCullers’ first career change. As a result, she found that fewer white families were sending their laundry out to African American washerwomen. She told King, “As I was a good cook and there was only a few places where [African Americans] could buy meals, I decided to open a small café for them to eat in.” She was successful enough in this first venture to see her daughters graduate from high school and to provide for her family’s needs.

A shift in Raleigh’s demographics and restaurant landscape pushed McCullers’ second career change. Greek immigrants arrived in Raleigh and began opening hot dog stands. Soon, according to McCullers, they expanded their menus to cater to an African American clientele. Her own café could not compete. When a neighbor built a hotel on nearby Cabarrus Street, McCullers leased it from him, installed a café, and ran both the eighteen-room hotel and the café successfully until the stock market crash of 1929.

As the country descended into the Great Depression, diners had less cash to eat out, and roomers sought cheaper accommodations. Women like McCullers struggled, too, as the costs of groceries and utilities went up. Dispassionately, McCullers said, “Well, I had to make a living somehow, so I gave up the hotel and came over here in this little place and started my boarding house.” Her decision to classify the restaurant as a boardinghouse was a strategic one: The fee for acquiring a restaurant license from the city of Raleigh was greater than that for a boardinghouse, so McCullers made sure her establishment had beds in the back rooms. Instead of offering short orders, she served three fixed meals a day, charging twenty-five cents a plate (or three dollars for a week’s worth of meals) and focusing on what she called “plain substantial grub.”

She described a typical menu to King:

For breakfast I’ll have fried salt herrings, mullets, sausage, pork chops, biscuits, cornbread and baker’s bread and coffee. I let them select whatever they want, but I do not serve them but one kind of fish or one kind of meat. For dinner I have cabbage, collards, blackeyed peas, stew beef, haslet stew, pigtail stew, pig ears stew, and water. I always have some kind of fresh fish for supper, pork chops, hog liver, coffee, and things like that. I fill their plates with as much food as I can get on them…I give them plenty of [cornbread] with their meals.

A coal stove, “patched in several places with tin, and held together by wire,” King observed, was the only kitchen equipment McCullers had to produce such a range of foods. While our first impression might be of quantity, a deeper look reveals that what McCullers called “plain” hid a world of complex flavors, skill, and transformation.

McCullers had clearly developed an arsenal of economical recipes. Stew beef then, as now, was often a mix of leftover cuts bundled together and sold cheaply. Pigtails, pig ears, and pig liver were all less desirable and less expensive parts of the hog. Haslet stew was made from liver, lungs, and sometimes heart. She relied on hardy vegetables with long growing seasons. McCullers shopped and cooked wisely while pleasing her customers and giving them reason to return.

McCullers’ list was deeply responsive to the foodways of the Piedmont in which she lived. Hogs are still plentiful today in eastern and central North Carolina, and they were crucial to twentieth century foodways there, even if some of the pork McCullers bought at the store was most likely of Midwestern origin. Adding regular fish dishes speaks to the connections between Raleigh and the rivers and coastal waters of eastern North Carolina. Collards are consumed all over North Carolina, but more so in the central and eastern counties. When McCullers said she gave her customers what they wanted, she knew what that meant.

Later in the interview, McCullers drew distinctions between what her customers wanted to eat when employed versus when they were out of work. She said she faced more competition from Greek restaurateurs when unemployment was high, because people could eat “a hamburger and a cup of coffee” and be “all right for several hours.”

When her customers had jobs “swing[ing] a pick or shovel all day,” then “that’s where I can beat the Greeks, because they don’t know how to fix vittles like collards, turnips, haslet stew and the other things,” she said, referring to to the dishes her African American clientele favored.

King observed that she had a “piccolo”—a nickel-fed juke box—with “the very latest blues recordings” on it, a picture of Joe Lewis hanging on the wall, and outdoor benches for people to gather. As a result, Della’s was “the gathering place for Negroes during the evenings and on Sundays.” We can only imagine the laughter, music, and community fellowship that took place there.

McCullers was a skilled, modern businesswoman. And Della’s was a success. During the years she ran the establishment, she supported herself and a disabled brother and paid school tuition for a grandson whom she hoped would become a doctor. Her liminal boardinghouse holds sophisticated stories of business acumen, community patronage, and everyday foodways that brim with a sense of place and purpose.

Elizabeth Engelhardt is the John Shelton Reed Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill and the chair of the SFA’s academic committee. She delivered a version of this article as a talk at the 2016 Southern Foodways Symposium.