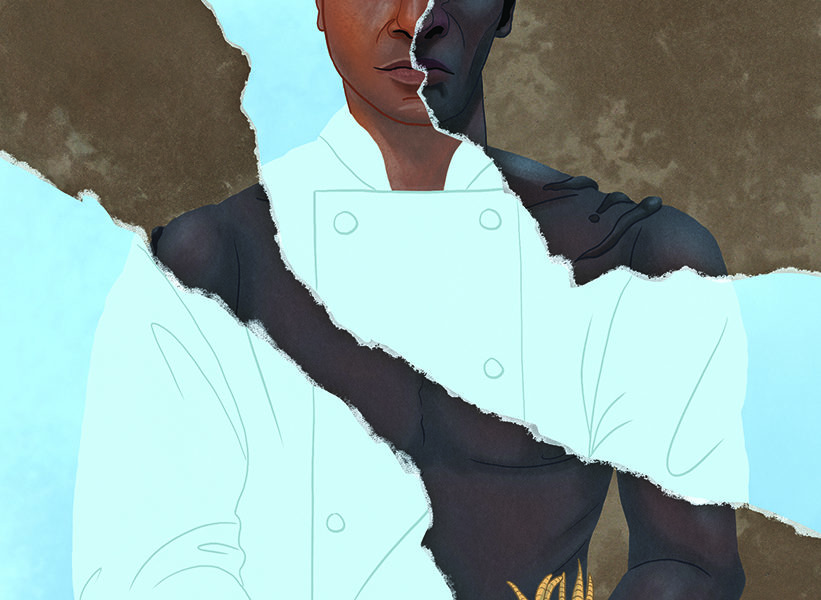

Your Fried Chicken Has Done Drag Atlanta’s boundary-busting queer food scene has roots in simple working-class diners.

by Martin Padgett

Sheena Cassadine whirls across the crowded restaurant, her pool wrap funneling into a rainbow tornado. Limbs twisting, one knee ricocheting to her side at a 90-degree angle, she whips and drops back-first to the ground in what drag queens call a “death drop.”

![]()

The patrons at Twisted Soul’s inaugural Atlanta Pride drag brunch watch in awe: Lithe twinks rub elbows with hairy bears and mingle with beautiful femmes, while servers deliver waffles and syrup to genderfluid folk who wear beachy dresses and toast each other with bottomless mimosas.

I fear for Sheena’s wig as she spins, but she has it under control. And, really, if you haven’t lost a wig over a plate of collards and fried chicken, have you really even done drag?

In this unabashed and unashamed haven, queer food doesn’t just mean a lush plate of Southern staples served by transgender people, cooked by lesbian chefs, or quaffed by nonbinary folk. It means ownership: Queer Atlanta owns this moment—and this place.

If you haven’t lost a wig over a plate of collards and fried chicken, have you really even done drag?

A generation ago, neither would have been true. The idea of queer food bubbled under the surface in Atlanta like stock under a pot lid. In that day, queer food meant something more akin to survival. It offered a welcoming plate for those who were no longer welcome in their own families. It became a substitute for the traditional family meal—one that nourished queer people better than the thin gruel they left behind on another table.

A half-century of queer food

Queer spaces had long hidden in plain sight in Atlanta. A growing LGBTQ community gathered discreetly at downtown cafeterias and diners like the Tick Tock Grille through the 1950s. By the 1960s, places such as Mrs. P’s, a restaurant by day that went discreetly gay by night, became well-known for their coded appeal. After the Stonewall riots that sparked the modern gay rights movement, queer people claimed public spaces of their own, at night clubs like the Cove and at restaurants like the Gallus, which served queer folk rack of lamb on white linen tablecloths upstairs while it gave sex workers a safer place to offer their wares in its basement bar.

Of the maybe dozen or so places where the queer community gathered, the Silver Grill was the everyday clubhouse. Set in a squat, whitewashed concrete building on Monroe Drive in Midtown, not far from the Strip, the Silver Grill spanned much of the hidden era of queer food in the South.

Carmen Walton opened the Grill on May 17, 1945, in an old Quonset hut purchased from the U.S. military as cheap surplus. From a menu the Silver Grill printed every day, diners ordered everything from fried chicken to bacon-wrapped filet mignon. In classic meat-and-three style, the Silver Grill served mashed potatoes with gravy, collard greens, and sweet-potato soufflé. For dessert, it dished out ruby-red cherries that poked out from under tawny sheets of cobbler.

The Silver Grill’s working-class food fed working-class patrons who came to build up a new Atlanta, reformatting its skyline with gleaming glass towers. Some were queer; over time, ever more of the customers who sat in the Grill’s worn vinyl booths and its chrome-rimmed Formica tables were lesbians, transgender, or gay. They came looking for a new home where they could find the homestyle cooking they’d left behind in Eufaula or Bristol or Waycross. No matter who sat at its tables, the diner served its fried chicken without the hostile sneer patrons might receive in their hometowns. The Silver Grill shone a beacon for Atlanta and burnished its reputation as a welcoming space. Queer people found comfort and community there, served with camp courtesy of the Grill’s patron saints: Peggy Hubbard and Diamond Lil.

Peggy Hubbard

A grainy 1984 video of a local-access cable-TV show captured the cozy and subversive microcosm of the Silver Grill. Bacon sizzles under a press on a flat top. The frame fills with handsome young men. Nearly everyone wears some sort of facial hair, other than the two seated at the green-vinyl booth.

Peggy Hubbard’s eyebrows rest flat on her forehead like hyphens. To her right, Cliff Taylor’s equally plucked brows rise when he poses questions. He’s used to the attention, even during the off hours when he’s not in drag as Tina Devore. Peggy is unnerved by the insistent camera but relaxes as Cliff asks about her long career at the Grill.

Peggy started waiting tables there in 1958, she tells Cliff. “We had a mixed crowd then,” she says, rattling off the names of customers she knows to be gay, who’ve waited for her to wait on them for years. “Curtis Chambers, who works at Texas Drilling [Company]…and Bill MacMillan’s a real old customer of mine; they’re both gay.”

She’d worked the Grill for 26 years already when the video was recorded. Her sweet smile and motherly cooing made her a celebrity in the queer Atlanta demimonde. “I don’t know,” she blushes. “I’m just nice to them, I’m real open-minded. They treat me nice and I treat them nice.”

When the AIDS epidemic hit, the Silver Grill’s food became the stuff of survival for some of its patrons.

The white smocks she wore when she waited tables made Peggy look like a nurse. By the 1980s, she would become one. By the time the video aired, Peggy had already begun to care for some of the young men who slid into those well-worn booths. When the AIDS epidemic hit, the Silver Grill’s food became the stuff of survival for some of its patrons. Peggy delivered food to friends and customers stricken by the disease, nourishing them with fried chicken, black-eyed peas, or whatever their declining bodies could tolerate. Some thought of her as a surrogate mother when their own had abandoned them. She visited them in the hospital when they grew too sick to come to her. She helped bury them.

Diamond Lil and the Silver Grill Blues

Peggy waited on the Silver Grill’s patron saint, the self-proclaimed “Goddess of All Grease and Glamour,” the “Queen of Diamonds,” Diamond Lil. Atlanta’s most famous drag performer, Lil was born Philip Forrester in 1935 in Savannah. As a boy of five, she had slipped into her mother’s satin pumps and sang “Don’t Fence Me In” for the neighborhood, until her mother tried put a stop to it.

Lil pioneered a sort of cosmic drag in Atlanta, wearing tunics and light makeup. She spoke in an ersatz Polari with syllables of French tossed into a word salad of her own making. She danced in wild swinging swoops. Lil bridged the old world of female impersonation with the emerging world of performance art.

Diamond Lil latched on to the very symbol of Southern tradition and twisted it into something altogether more lecherous—and delicious. She queered it.

She sang about Atlanta’s darker and more interesting corners in songs such as “Queen of the Dunk ’N Dine,” but saved her most tasteful grease for her diner home. She wrote “Silver Grill Blues” in 1975 and composed it nearly entirely in double entendre. The lyrics retell a fantasy of Lil’s, in which she spots a yellow-helmeted lineman and falls in love, only to find out he’s married. She coos: “I lost my heart tryin’ to get my fill when I ate at a country diner called the Silver Grill.” She sang “Silver Grill Blues” at nearly every show she performed and passed out fried chicken from the stage. She latched on to the very symbol of Southern tradition and twisted it into something altogether more lecherous—and delicious. She queered it.

Closing time

The Silver Grill was a throwback, but throwbacks come with problems. The restaurant used a hand-cranked cash register, had very little parking, and needed more than a hundred thousand dollars in upgrades. In December 2006, rather than renovate, the Silver Grill’s owners decided to shut down.

Peggy waited tables until it closed, while manager Kevin Huggins filled the Grill’s ancient till with its last dollar bills. Wearing a blue blazer with a trademark pink scarf, Diamond Lil tucked into a final round of blackberry cobbler before the landmark closed. She confessed at the end that the “Silver Grill Blues” was inspired less by the meals she ate than by the men she cruised. “You would come in mostly for the food,” she said, “but the ambience was certainly a selling point, too!”

Peggy had planned to work over at the other “gays and grays” eatery in town, the Colonnade, but returned instead when new owners re-opened the Silver Grill in 2007. The revival would be short-lived; the Silver Grill closed for good in 2009. Peggy Hubbard died a year later. When Diamond Lil passed in 2016, friends handed out fried chicken at the memorial and closed the Silver Grill chapter of Atlanta’s queer history.

Twisted Soul’s new queer food

When she lived near the neighborhood, Twisted Soul’s Deborah VanTrece would bring her young daughter Kursten to the Silver Grill. “I felt like I had stepped back into another time,” she remembers. “It was just good old country food, and there was a little bit of everybody there.”

VanTrece came to Atlanta in a straight marriage, with a job as a flight attendant. She came out as a lesbian, got a divorce, and took her memories of the Silver Grill with her as she put herself through the Art Institute of Atlanta’s culinary program, where she graduated at the top of her class. She met her future wife, Lorraine Lane, while she worked toward opening her own restaurant.

VanTrece and Lane count themselves among the latest generation of queer food to emerge in Atlanta. The duo opened the first iteration of Twisted Soul in Decatur in 2015, then moved it to West Midtown in 2016.

They run the restaurant family-style, meaning the whole family runs the restaurant. They pair Lane’s cider-infused, marigold-garnished Adam’s Demise cocktail, with a cast-iron burger grilled the way VanTrece’s grandma Lueticia would grill it. Their daughter Kursten helps manage the restaurant. They serve their version of queer food with a welcoming space and acceptance.

“Every day I watch people, couples, same sex, hand in hand, walk in,” says VanTrece. “Their heads are up, and they’re proud of this place. … It’s one of the most fulfilling things about owning Twisted Soul.”

Lane adds: “A transgender person came into our space looking for a job and came in proud and felt proud and felt accepted,” Lane says. “I think that is a true sign of the progress that we’re making.”

Today, that progress is also measured in the number of red-velvet muffins that rush out of the kitchen, and in the number of bottomless mimosas that get refilled as the couple caters to the community that considers Twisted Soul its home and Drag Brunch during Atlanta Pride 2019 its homecoming.

A whirl of illusion

The music comes up when I flick the light on in the Twisted Soul restroom. It’s like Superman’s phone booth for drag queens in here, an impromptu dressing room stocked with safety pins and scissors and a blue Cleopatra gown.

I get back to my table just in time. My fried chicken hasn’t been hurled at the audience by a drag performer, but maybe with the right tip it could be. It deserves worship—and so does Sheena, who erupts into her lip-sync number before I can take a bite.

She dives and throws dollar-bill tips in the air. She spins until the rainbow fringe on her shimmy-shirt orbits her like the rings of Saturn. She pops and locks, she breaks, she lays out, she dips. Sheena is the latest eyewitness to more than a half-century of queer food in Atlanta. And she is loving it, honey. She is owning it.

Martin Padgett writes stories about LGBTQ culture from Atlanta. His book Midnight at the Oasis: A Decade of Drag, Drugs, and Disco at the Sweet Gum Head, will be published in 2021 by W.W. Norton.