Trawling for Shrimp Excerpted from Buttermilk Graffiti

By Edward Lee

Illustrations by Ran Zheng

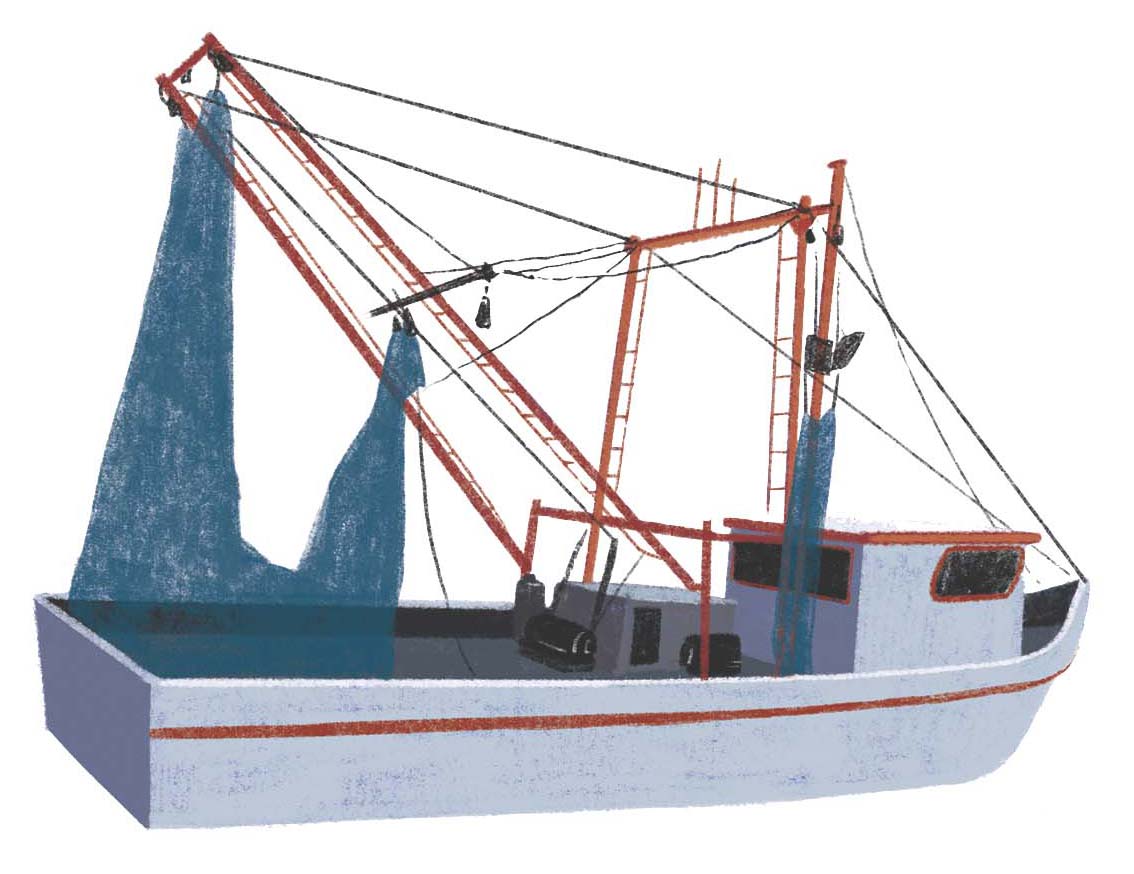

Crossing from Seabrook into Kemah, for a moment I get the feeling I’m floating on air—the highway elevates so swiftly over the piers. To my left is a clear view of the rich blue waters that stretch into Galveston Bay. The color mirrors the Texas sky. I am on my way to Galveston to secure a shipment of Gulf shrimp for my restaurant.

It is something I have to have on my menu. Shrimp crosses all culinary borders. From the pages of Nathalie Dupree’s Shrimp and Grits Cookbook to the melamine plates of Vietnamese crepes stuffed with shrimp and pork to chilled martini glasses of shrimp cocktail served at every steak house in America, shrimp are adored everywhere. I’ve tried to avoid shrimp on my menus, but the demand is just too high. Americans consume about 1.3 billion pounds of shrimp annually. So here I am in shrimp country, to see with my own eyes an industry that has been much maligned. If I’m going to cook with shrimp, I need to find a source I can trust.

If you eat shrimp regularly, chances are they come from Southeast Asia, where they were most likely farmed in overcrowded mud ponds manned by poor subsistence workers barely able to eke out a living. These shrimp swim in a toxic cocktail of fertilizers and antibiotics, to ward off the host of diseases that infect these monoculture-breeding facilities. Still, chances are the shrimp don’t taste all that bad. Most farmed shrimp from Asia have no detectable flavor, good or bad. Once you dust them with paprika and cumin and blacken them in a cast-iron pan, or drown them in a spicy sweet-and-sour sauce, it matters little how flavorless they are. It is easy to overlook the chemical bath they were treated in before they arrived in frozen five-pound bricks. Shrimp are a cheap commodity, the equivalent of aquatic vermin.

“They will not talk to you. Mostly, they want to be left alone.”

I pull into a Vietnamese restaurant in Kemah. All along the Gulf Coast, from Seabrook to Galveston to Palacios, Vietnamese fishermen have settled into communities that started when thousands of refugees were relocated here after the Vietnam War. I sit down and order báhn xèo, a popular dish on the menu in every Vietnamese restaurant in America. It is a light, crispy crepe of turmeric and rice flour folded over shrimp, pork, and bean sprouts and served with a sweet dipping sauce. The place is bright and airy. The customers are white and working class and polite. On my table is the familiar plastic chopstick holder that opens up when you pull a knob on the lid. Bottles of Sriracha and soy sauce sit on a plastic tray. My waitress goes back and forth between taking orders and studying an oversize textbook.

I pull into a Vietnamese restaurant in Kemah. All along the Gulf Coast, from Seabrook to Galveston to Palacios, Vietnamese fishermen have settled into communities that started when thousands of refugees were relocated here after the Vietnam War. I sit down and order báhn xèo, a popular dish on the menu in every Vietnamese restaurant in America. It is a light, crispy crepe of turmeric and rice flour folded over shrimp, pork, and bean sprouts and served with a sweet dipping sauce. The place is bright and airy. The customers are white and working class and polite. On my table is the familiar plastic chopstick holder that opens up when you pull a knob on the lid. Bottles of Sriracha and soy sauce sit on a plastic tray. My waitress goes back and forth between taking orders and studying an oversize textbook.

When the crepe arrives, I can tell the shrimp is not from the Gulf. I ask the waitress, but she tells me she doesn’t know. I’m hungry, so I finish what’s on my plate, wondering as I eat if it is more authentic for a Vietnamese restaurant to use frozen shrimp farmed in Vietnam than Gulf shrimp. Then I wonder if any of the restaurants here use the local shrimp, or if the lure of cheap imports is just too tempting. The waitress tells me she is a college student studying for an exam. This is her uncle’s restaurant; her aunt is the cook. I tell her I’m here to interview Vietnamese shrimpers and could she ask her uncle if he knows any. She doesn’t hesitate to answer.

“They will not talk to you,” she says bluntly. “Mostly, they want to be left alone.”

“Is it because of all the racial stuff that happened here in the past?”

The relationship between the Vietnamese fishermen and the local Texas fishermen has long been punctuated by controversy; skirmishes have boiled over into fights and even murders. After the Vietnam War, when thousands of refugees were placed along the Texas Gulf, many did what they knew how to do best: fish. This was a time before stringent regulations, and the Vietnamese, desperate to make a living, broke many of the unwritten rules of the bay. They skirted laws, they ignored limits, they transformed an old Texas profession into a cutthroat business. This behavior coincided with the rage many Texans felt over unfair demon-ization of American Vietnam War veterans. Though the immigrants were on the same side of the fight in Vietnam as Americans, here in Texas, tensions between Vietnamese and white fishermen ran hot like a breezeless summer night. The strife was further complicated by a growing industry of cheap farmed shrimp from Southeast Asia flooding the American market, driving shrimp prices to all-time lows. Many of the Texas old-timers were pushed out of business. Many blamed the Vietnamese for eroding a way of life that, on the Gulf Coast, was more than just a profession; it was a tradition. Others argued that the shrimp industry was already in decline with or without the Vietnamese. Even so, the tensions ignited into violence. Vietnamese shrimp boats were burned, shots were fired, rallies were held, and at one point, the KKK got involved. A generation of mistrust and resentment ensued.

“They came here to work, not to fight.”

This was more than thirty years ago, and the hatred has subsided, I’m told. Still, the local industry has been steadily constrained by catch limits, overfishing, oil spills, and increasing environmental regulations, and all the while, the amount of imported shrimp continues to rise. The Vietnamese shrimpers fare no better today than anyone else suffering in an industry that is being choked from all sides. I’m told that nowadays everyone gets along because no one is doing any better than the next guy.

“That was a long time ago,” the waitress says. “I’m too young to remember all that.”

Her aunt comes out of the kitchen, and I awkwardly thank her for a delicious meal. She doesn’t speak much English, and my waitress, eager to get back to her studies, does not volunteer to interpret. I pack up my notebook, but then, just as I am about to leave, the young waitress turns to me suddenly and says, “During the war, everyone came to Vietnam and burned it down, so they had no choice but to leave. They came here to work, not to fight.”

Excerpted from Buttermilk Graffiti by Edward Lee (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2018

Edward Lee is the author of Smoke & Pickles; chef/owner of 610 Magnolia, MilkWood, and Whiskey Dry in Louisville, Kentucky; and culinary director of Succotash in National Harbor, Maryland, and Penn Quarter, Washington, DC. Find tour dates for Buttermilk Graffiti at chefedwardlee.com.