Southern, Reborn My Boiling Springs became a wellspring

by Monique Truong (Gravy, Spring 2016)

I was born in Saigon, South Vietnam, in 1968.

I was reborn in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, in 1975.

Not a “rebirth” in the religious sense of the word but in the shape-shifting transformation that refugees and immigrants undergo upon our arrival here in the U.S. With a new language, often a new name, and always a new daily bread, we necessarily become someone new. For a child, this metamorphosis is even more acute and thorough.

I was seven when my family came to Boiling Springs as refugees from the Vietnam War. I didn’t add the English language to my Vietnamese. I traded it wholesale. Now when I try to speak my first language, I’m told that my accent is cứng, which in this context means the opposite of supple. In my new home, the given name that I answered to during my young life became, literally, a dirty word. I went from Dung—the “D” is pronounced like a “Y”—to Monique, a name on my Catholic baptismal certificate but otherwise never used. As for my daily bread, it found companionship and comfort with slabs of hickory- smoked bacon, thick slices of sugar-cured ham, and country sausages, flecked with black pepper and generous with sage.

Within two years in Boiling Springs, I was a baton twirler, one of the quintessential rites of passage of Southern girlhood.

I’ve a photo that was taken in 1977 in the nearby town of Shelby, North Carolina.

I like to think that I’m a part of their collective memory as much as they are a part of mine—that we belong to each other.

I was nine years old, marching with my baton-twirling troupe in the annual Christmas Parade. Our mothers had been given mimeographed sheets with detailed instructions about our costumes. Where to mail-order the skirted red leotard, how much white fur trim would be needed for hand-sewing around its neck and skirt, satin ribbon for our hair, a pair of Keds (brand new or well-painted with white shoe polish, which I think was the frugal option we went with), white ankle socks (my mother bought two pairs because she didn’t want my feet to get cold), beige pantyhose (also two pairs for the same reason of ensuring warmth). On the morning of, underneath the leotard’s polyester, my mother stuffed me into a thick acrylic sweater (again, for the frigid temperature, which judging from the photo and the way that the folks lining the street were dressed, was probably in the low fifties).

The inner sweater was unbearably itchy; my sneakers didn’t fit because of the extra pair of socks; sweat was dripping down my back because Shelby was a small town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, not the Antarctic; and, in all honesty, I still wasn’t quite sure why I was waving a metal rod around. Was it a kind of dance? A form of martial arts? Had my mother enrolled me in a paramilitary corps, like those cookie-pushing Brownies?

This was the first and only time that I would march in the Shelby Christmas Parade. My family moved to Centerville, Ohio, the following summer. My baton twirling days were over. In southern Ohio, girls my age played soccer. Maybe they twirled batons, too, but I was never again one of them.

Photographs are taken to memorialize something consequential—a moment of celebration, a noteworthy place and time—and they are also taken as evidence and proof.

I like to think that this nine-year-old and her baton showed up in other people’s photos from that day, too, inhabitants of Cleveland County who had lined the parade route, whose photos are now as faded as mine, their Kodachrome colors washed-out, except for the still-vivid red. I like to think that in this way I’m a part of their collective memory as much as they are a part of mine. You know, that we belong to one another.

This photo documents a small Southern town being itself. Whites, African Americans, one lone Vietnamese American girl, we are all inside this frame. The photo isn’t an idea of a small Southern town, constructed elsewhere, mass-marketed, and reflected back onto itself and places beyond for instantaneous messaging and ready consumption. It takes more than a split second to understand. It requires explanation, context, and a willingness on the part of a beholder to embrace complexity, plurality, and flux.

What happens when I claim my Southern rebirth as an inspiration, as raw source material, and as the living connective tissue to a specific alimentary and literary tradition that gave birth to my novel?

So, what happens when this little girl grows up and writes a novel, conceiving it as a re-imagined Southern Gothic, setting it in Boiling Springs and Shelby, and writing a version of herself as the novel’s narrator, a child who is profoundly different from her community in many ways, beginning with her synesthesia, a neurological condition in which her words are accompanied by phantom flavors, most of them lifted from a Southern table? (The word “later,” for instance, brings with it the richness and tang of pimento cheese, “fiduciary” a sweet pull of Cheerwine, and “character” serves forth pickled watermelon rind, with its equal parts vinegar and sugar with a linger of cloves.)

In other words, what happens when I claim my Southern rebirth as an inspiration, as raw source material, and as the living connective tissue to a specific alimentary and literary tradition that gave birth to my novel? Harper Lee, Carson McCullers, and North Carolina’s own George Moses Horton—a man who began his life as an enslaved person and who became the first African American poet to be published in the U.S.—I wrote their names into the pages of my novel in homage to what they meant to me as a reader, a writer, and a human being.

All this and more I shared with my publishing house when I was asked to fill out an author’s questionnaire, detailing background and personal information, in order to help them with marketing and publicity: How did I get the idea for the book? What’s my personal connection to the subject matter? What areas of the country do I have a connection to?

My publisher wanted to know how best to package my book and how best to package me. My novel would emerge out of this process a fully fungible object, encased in a shiny wrapper, designed to entice readers and to promise, in a glance, what they would find on the pages inside.

A novel’s cover design is the clearest indicator, an unequivocal pictorial representation, of what the publisher has distilled its content and its author down to. At first, I was shown two proposed covers for my second novel, Bitter in the Mouth.

One features a bare-chested woman made modest by two strategically placed red roses, festooned with golden arabesques, and hidden in the shadows. Maybe, behind that scrim of darkness, she’s in fact sitting in front of a jumbo plate of chopped pork and hushpuppies from Shelby’s own Red Bridges Barbecue Lodge. For her sake, we can only hope that’s the case, as it would have kept her warm in her inexplicable state of undress. The other cover depicts a partially clothed gal in profile with a platter-sized, wine-red hibiscus in her hair. She looks like she’s starving for a meat and three.

Neither one of these images signals to me a novel set in the American South; a coming-of-age novel and a family narrative that takes place from 1975 to 1998; nor a food-laden snapshot of a girl whose words are coupled with the foodstuffs that graced the Southern table as well as the food facsimiles that disgraced that table during an era when convenience relentlessly pummeled flavors. The South in the mid-70s for me was a Janus-like feast of boiled peanuts, Red Velvet cake, buttermilk biscuits, ambrosia salad, fried okra, and peach cobbler at one end, and at the other sodden corpses of vegetables in cans, albino sponges marketed as loaves of bread, and gelatinous condensation of soups, which we were all encouraged to use for making absolutely everything as long as it wasn’t just soup.

I found these two cover designs laughably and disturbingly misrepresentative of my novel. As a former attorney, I would even say that they constituted false advertising. Couple these designs—and there were others that were far worse, and none included a morsel of food—with the face-to-face meeting in which I was told that the marketing and publicity material wouldn’t in any way characterize my book as a Southern novel. Though I can’t remember the exact words, they were something close to this: We’re going to steer clear of that. My publishing house wanted to steer clear of my novel’s regionality, as if its Southern milieu was roadkill or a pothole or an unexploded landmine. Better back it up and go another way. From the look of these designs, I think the direction that my publisher was heading toward was South America. An Isabel Allende or a Gabriel García Márquez novel would look almost at home underneath these covers.

A Vietnamese American woman writing a coming-of-age novel set in and fed by the American South wasn’t a selling point.

What was left unsaid during the meeting was too embarrassing and damning to say to my face: My publisher believed that American readers would not buy, literally and figuratively, my book if it was packaged as a Southern novel. Their assessment was that a Vietnamese American woman writing a coming-of-age novel set in and fed by the American South wasn’t a selling point because I, the author, was an anachronism. I was hard-to-believe and improbable. My palate and my dinner plate were limited by my race. I had no easily understood or identifiable role within the publisher’s flat, static, binary, black-and-white idea of the American South. In the parochial world of New York publishing, if the editors, marketing executives, and publicists can’t imagine it, then, of course, the book-buying public at large—rubes that we all are—couldn’t as well. Within the limited territory of my publisher’s imagination, that was the end of the story, and it would not be a Southern story.

Except in my case, it wasn’t the end, because I had a dogged literary agent on my side, a bestselling novel already to my name, and was—and still am—stubborn as a mule. The point for me was Crystal Gayle clear: To deny the Southern origins of my novel was to deny me of my Southern girlhood. It was hard work twirling that baton, hard work to attend classes every week with little girls—all of them white—who assiduously ignored me because my newly arrived mother had no idea that by enrolling me in their class that she and I had violated an otherwise well-understood color line, and even harder work to smile through it all. No New York publishing house was going to erase me from Boiling Springs and Shelby. These places belong to me, and I to them.

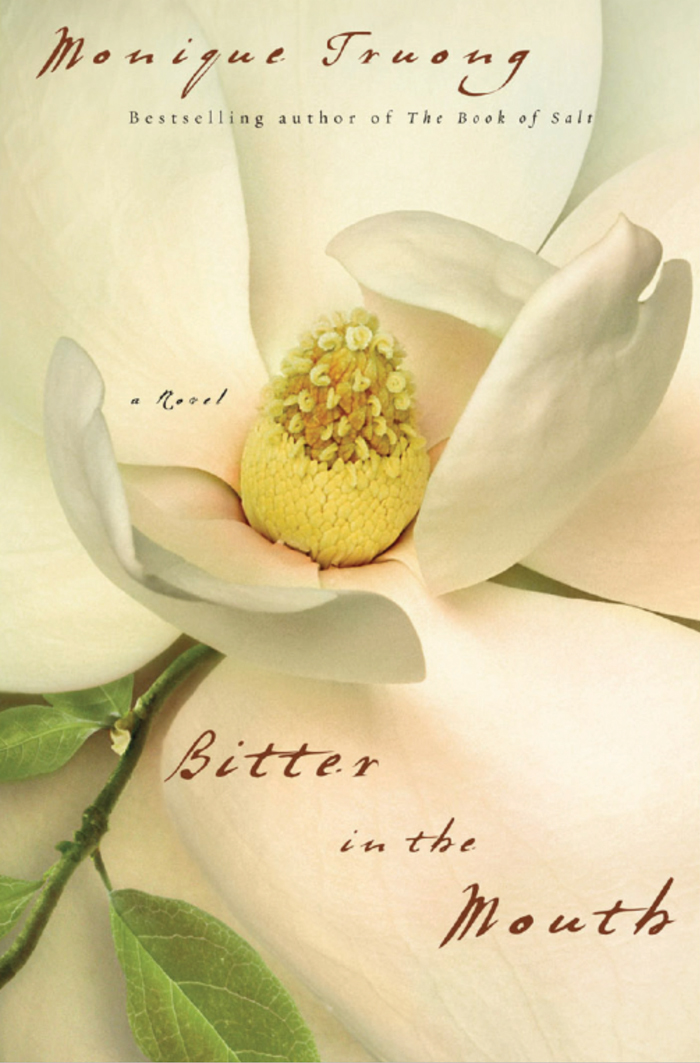

In the end, I had to come up with my own ideas and proposals for the book cover, which finally led to an agreed-upon design: the interior of a wide open magnolia rendered in the soft hues of nostalgia.

Of course, I told my publisher that the state flower of North Carolina is the dogwood, not the magnolia, which is Mississippi’s own. That was too fine a point for them. Despite their better judgment, they were heading southward after all, but they weren’t going to consult a map and get all state-specific about it. Mississippi’s magnolia went on my paperback cover as well.

On both editions, you’ll notice that my bio includes no mention that I lived in Boiling Springs. It says only that I live now in New York City. In my interviews and during my readings and appearances, I always offer up this fact and connection because it’s meaningful and poetic justice that my Boiling Springs became a wellspring.

Given my publisher’s haphazard steering, I’m amazed that the Atlanta Journal-Constitution found their way to Bitter in the Mouth. The Charlotte Observer did too, and the novel and I ended up on its front page. Even the Earl Scruggs Center, located in the very heart of Shelby, found it and me. Every time another Southern institution contacts me, I give thanks that I stood up for my novel and for a depiction of the American South supple enough to include this little girl.

As Theodore Roosevelt would say if he, like me, had been reborn a little girl in Boiling Springs, “Speak softly and carry a big baton.”

The Asian-American Experience in the South on Gravy

Halo Halo: Growing up “Mix Mix,” Filipino in the American South (Gravy Ep. 37)

When Alexis Diao’s father arrived in Tallahassee, Florida, he couldn’t even find coconut milk—let alone many other ingredients to make the Filipino food of his home. Listen >

A Trailer, a Temple, a Feast: Making Laos in North Carolina (Gravy Ep. 31)

Sticky rice. It may not be the first dish you expect to be served in a double-wide trailer in the mountain South, but in Morganton, North Carolina, you will find it in abundance. Listen >

Monique Truong is the author of two novels, The Book of Salt and Bitter in the Mouth. Her third novel, The Sweetest Fruits, is forthcoming from Viking Books. She presented a version of this piece at the 2015 Southern Foodways Symposium.

Monique Truong is the author of two novels, The Book of Salt and Bitter in the Mouth. Her third novel, The Sweetest Fruits, is forthcoming from Viking Books. She presented a version of this piece at the 2015 Southern Foodways Symposium.