BARBEKUE How barbecue marked the rise and fall of the Texas Klan

By Daniel Vaughn

The rain wouldn’t stop. Pits filled with water, and the stacks of wood soaked through. The barbecue had to be canceled. The Klan celebration would continue, but the rain drenched hopes of a more grandiose ceremony. Texas Governor Ma Ferguson denied them horses for their initiation ceremony.

![]()

The year was 1925, and the place was Arlington, Texas. Klan klaverns 66, 101, and 334 from Dallas, Fort Worth, and Oak Cliff, respectively, had planned the barbecue and accompanying ceremony “to demonstrate the fact that the Klan is not dead,” the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported. But when just a fraction of the expected attendees showed, it marked the last gasp of the Klan as a social and political force in Texas.

This is a story about Texas in the 1920s that remind us of what happens when overt bigotry becomes socially acceptable. During that era, the Klan wrapped their racist anger in a shroud of morality and sought acceptance through false patriotism, using massive barbecues to draw onlookers and potential recruits with food and drink. Their aim was to normalize their group for a curious public who had likely read media accounts of the Klan’s vigilante violence, signature burning crosses, and hooded marches.

During the 1920s, Texas klaverns marched along city streets at night, without prior notice, and in full Klan regalia. At secret initiation ceremonies in rural areas, heavily armed hooded figures stood watch at entry points. Klaverns often planned these events around barbecues, at first because it was an easy way to feed their members at secluded meetings. Robin Hood, editor of the Matagorda County News, reported from a barbecue in October of 1921. Stephen F. Austin Klan No. 5 members drove Hood past armed guards to a field outside tiny Clemville, about twenty-five miles north of Matagorda Bay. There he saw “a pit as long as the News office contained the coals that glowed under the carcasses of five or six beeves.” The editor shared a meal with his hosts, but when the initiation of seventy new members began and the organizers lit a cross, he watched from afar.

At the conclusion of the barbecue, Hood’s hooded source, who had a poor grasp on irony, told him “the Klan had nothing to hide.” Back then, the Texas Klan, which had begun organizing in 1920, wasn’t a socially acceptable club to join. They whipped, beat, and maimed victims they deemed immoral. They threatened preachers and teachers who did not teach their lessons in English. Blacks, Jews, immigrants, and Catholics: Anyone from those groups who dated outside their race might be tarred, feathered, or forced out of town. Brutish, racist, and terrifying, the Klan did much of this under a cloak of strict secrecy. At least in the beginning.

At the time, the Klan’s doctrine was only mildly controversial to the conservative white public, inspired by The Birth of a Nation, the D. W. Griffith film. In the fall of 1915, the film began a four-year run in Dallas and Forth Worth theaters. The three-hour epic was as devastatingly racist as it was cinematically groundbreaking. President Woodrow Wilson screened it at the White House. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram hosted a movie-themed essay contest for school children. The newspaper gifted winners with tickets to a local screening.

The film blamed the South’s post-war upheaval on Northern “carpetbaggers” and portrayed newly elected black politicians as corrupt buffoons. The hooded white knights of the original, first-era KKK were the protagonists. In the film, their final heroic effort was to patrol the election-day streets on horseback, guns drawn. Wearing full Klan robes, they aimed to keep black voters from reaching the polls.

By June 1922, the Klan had established its presence in Texas. In Waco, the local klavern planned “the largest meeting that had been held in the history of that organization,” according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Fifteen thousand reportedly gathered in a field four miles west of town to initiate two thousand new members. The event was closed to the public, but the Klan invited reporters to witness portions of the initiation and enjoy the feast, which included “five tons of beef and one ton of goat, which were barbecued in a pit 900 feet long.” The paper reported that “among the men preparing for the barbecue Thursday afternoon were 25 negroes who were peeling potatoes and onions.” Under the glow of a fifty-foot tall burning cross, black men fed white men whose mission was to prolong and deepen their oppression.

A couple of months later in Bonham, Texas, the barbecue didn’t go so smoothly. “Negros Would not Dig for the Ku Klux Klan,” proclaimed the Sherman Daily Democrat headline. The Klan had hired a group of black men to cook barbecue for an initiation ceremony. When the unidentified cooks arrived, no pit had been dug. The Klan organizers had expected the black men to do that work, but the cooks balked. “In the end,” the Sherman Daily Democrat reported, “white men had to be employed to do the work.”

In 1922, Texas membership in the Klan doubled from 75,000 in January to 150,000 by the end of the year. As membership grew, the Klan developed a message that was palatable to skeptical whites. Large newspaper ads announced meetings, often simply called barbecues. A 1923 advertisement promised a members-only “Big Klan Barbecue” in Georgetown. The same year the public bought $.25-seats to a huge Klan initiation planned in San Antonio. If you knew a klansman, you could come as their free guest to the preceding barbecue.

In November of 1922, a Dallas dentist named Hiram Wesley Evans ousted the longtime Klan leader William Joseph Simmons. As the new chief, Evans sought political power for the Klan, which already held many city government positions in Fort Worth, Dallas, Wichita Falls, and Waco. Now the Klan wanted statewide office. “Klan candidate” Earle Mayfield, an East Texas native, had just been elected to the United States Senate. Evans saw the opportunity for more power, but the Klan would have to convince the electorate that they had shed their terroristic ways. The organization needed a public relations campaign.

In November of 1922, a Dallas dentist named Hiram Wesley Evans ousted the longtime Klan leader William Joseph Simmons. As the new chief, Evans sought political power for the Klan, which already held many city government positions in Fort Worth, Dallas, Wichita Falls, and Waco. Now the Klan wanted statewide office. “Klan candidate” Earle Mayfield, an East Texas native, had just been elected to the United States Senate. Evans saw the opportunity for more power, but the Klan would have to convince the electorate that they had shed their terroristic ways. The organization needed a public relations campaign.

Caleb Ridley, the Klan’s designated chaplain, led that public relations effort. An Atlanta-based Baptist minister who had begun his career in Beaumont, Texas, Ridley toured the country as a Klan speaker. When questioned about the Klan’s exclusivity, he compared their membership requirements to that of the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic organization that excluded Protestants. The message seemed to be “we’re not racist, we’re just picky.”

Evans denounced the violence committed by some “rogue” members, and promised that their dedication to law and order would translate as deference to the police. The Klan also curried favorable newspaper coverage of its charitable donations, and tried to align the Klan politically with the temperance movement. Their goal was “True Americanism.” Recruits who bought their double-speak believed the Klan didn’t dislike or look down on other groups. They just wanted to fellowship, and barbecue, with their own.

Public support for once-popular anti-Klan laws waned. Protestant ministers became persuasive apologists. Their agendas of temperance and morality aligned. Klan processions interrupted church services to make symbolic donations to ministers—imagine the impression that made on congregations. Klan speaking tours emphasized piety and their own brand of distorted patriotism. Before large audiences, they stumped for their preferred political candidates. Candidates sought Klan endorsements. Being labeled the “Klan candidate” was no longer dishonorable.

In response to the Klan marches of the early 1920s, many cities and towns had enacted anti-masking laws, but the issue didn’t seem to matter as much as the Klan became more palatable. By 1923, hoods weren’t as necessary in public. Fully costumed speakers commonly removed their hoods on stage. Even initiation events, once held in strict secrecy, were open to the public. A newspaper ad for a Klan barbecue in Elgin, Texas, promised, “Everybody Invited.” Texas has a long history of large-scale community barbecues to celebrate holidays, civic achievements, and milestones. These Klan events were built on that model, but were aimed at a far less diverse crowd. Conservative whites didn’t question them. In just three years, the shame had disappeared, right along with the secrecy.

“The first public Klan ceremonies were austere and mysterious,” wrote Scott M. Cutlip in The Unseen Power. “But as the rallies increased in size they became less supernatural in character. More and more Klansmen brought their families. Barbecues were held to feed the crowds. By 1923, the hours of mystifying ritual at the initiation came more and more to resemble a high school baccalaureate.”

The Klan held its largest and maybe most widely publicized barbecue on the shores of Lake Worth in Fort Worth. “Kodak Klicks as Klansmen Kook Barbekue and hold Piknik” read the September 23, 1923 Fort Worth Star-Telegram headline. To document the preparation of sixty-five Hereford steers over a three-hundred-foot-long pit, the Klan called in the newspaper’s photographer. None of the cooks attempted to hide their identity. In the photos, one wears a badge that reads “Imperial Chef,” and another, “Boneless Meat Kutter.”

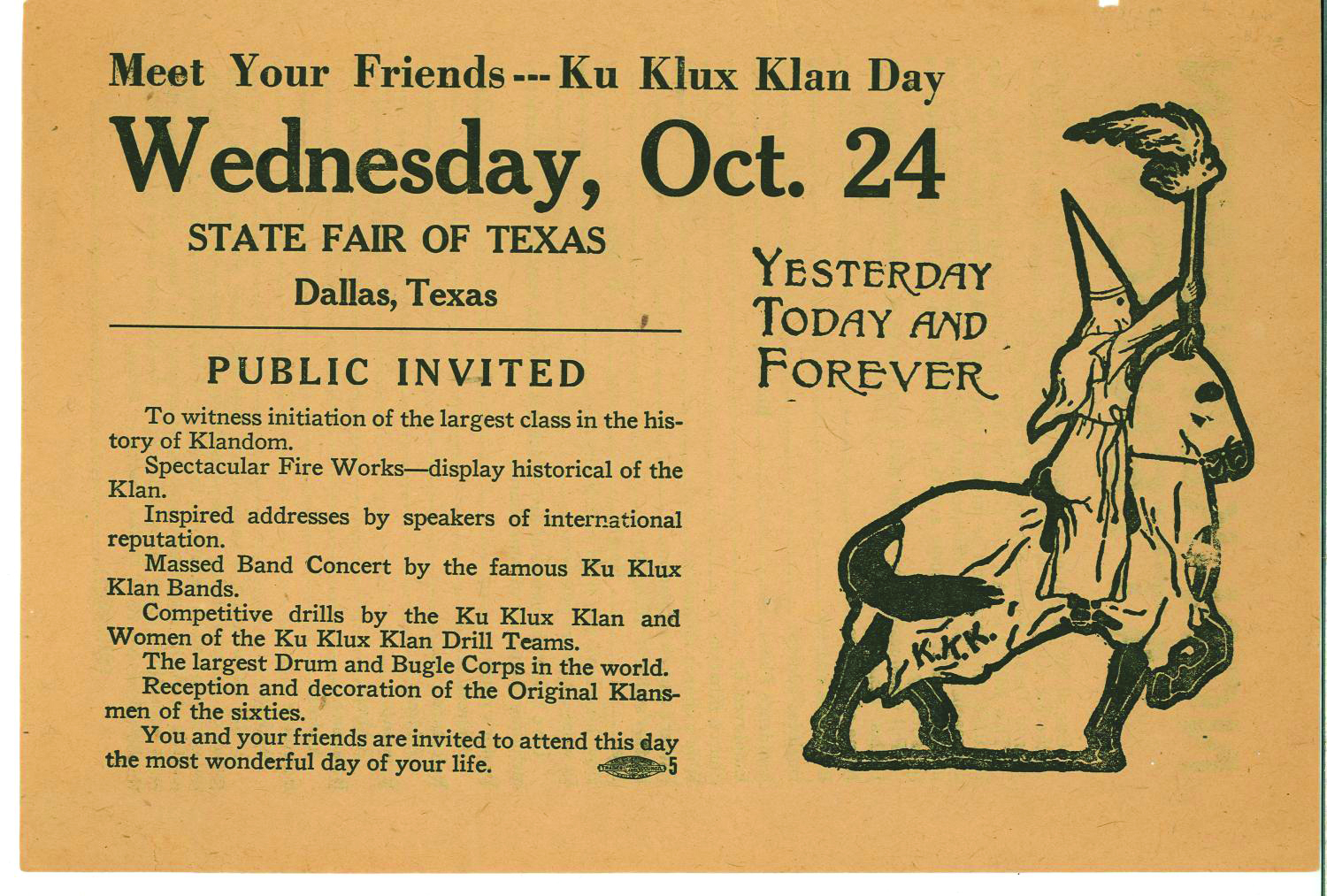

The following month in Dallas, the Klan got the sort of public recognition they wanted when the city dedicated one day at the State Fair as “Klan Day.” The Klan distributed applications at the gates. During a rodeo event, a bull rider wore a Klan robe and hood. The WPA Dallas Guide and History described it this way: “Under the eyes of Imperial Wizard Hiram W. Evans, 5,631 male candidates and 800 women were ‘naturalized’ into the ‘Invisible Empire’ before the grandstand at Fair Park with 25,000 onlookers.”

That day, Evans spoke of “The Menace of Modern Immigration.” The Klan had spent the previous year or so trying to soften their rhetoric, but the rough edges showed during Evans’ lengthy diatribe. In a nativist rant, Evans blamed the nation’s problems on “illiterate, disease-ridden stock” from Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Eastern Europe. His term for all of these groups, including African Americans, was “unassimilable.” He said that they simply lacked the capacity to fully assimilate and become true Americans. He was quick to add, “There is not a semblance of racial hate in my heart.” By the numbers, the Klan was at its peak in Texas, but its popularity was about to take a tumble.

The 1924 Texas governor’s race would prove a monumental failure for the Klan. Dallas judge Felix Robertson had openly accepted the group’s support. He toured the state, stumping at Klan rallies and barbecues. Ma Ferguson was his Democratic competition. Banking on a lack of Klan support in rural Texas, she ran an anti-Klan and anti-Prohibition platform. A week before the primary vote in July, the Klan appeared to be gaining a foothold in west Texas. But that momentum would not last.

The 1924 Texas governor’s race would prove a monumental failure for the Klan. Dallas judge Felix Robertson had openly accepted the group’s support. He toured the state, stumping at Klan rallies and barbecues. Ma Ferguson was his Democratic competition. Banking on a lack of Klan support in rural Texas, she ran an anti-Klan and anti-Prohibition platform. A week before the primary vote in July, the Klan appeared to be gaining a foothold in west Texas. But that momentum would not last.

After a secret initiation and barbecue in San Angelo, a parade proceeded through downtown. It began in grand fashion, but an unidentified hero had planned a message for them, according to a Dallas Morning News report. “When the marchers were a block distant, San Angelo’s big electric ‘Welcome’ sign over Chadbourne street, switched off and did not blaze again until the robed figures had departed.” It would become a prophetic symbol for the Klan in Texas.

Ferguson trounced Robertson to become the Democratic nominee and de facto winner. She used the win to include a specific denouncement of the Klan in the Texas Democrats’ official platform. But Fort Worth klansmen carried on as they had the year prior. They served a crowd of 10,000 at a Klan barbecue at Lake Worth, outside Fort Worth. They staged boxing matches, and klansmen closed the event with a sing-a-long and a “battle royal between five negroes,” in which the losers were “hurled into the gaping waters of Lake Worth.”

No matter. Klan membership in Texas steadily fell, dropping from a height of 150,000 in 1922 to 97,000 in 1924. Within two years, membership would plummet to 18,000. In July of 1925, the Fort Worth city manager fired all Klan members in city government. In defiance, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the Klan burned forty “indignation crosses” around Fort Worth, and planned a massive barbecue celebration for September 12 in Arlington. The Texas Mesquiter announced that “the biggest Klan event ever held in the South” was expected with 100,000 attendees and a class of one thousand initiates.

On September 11, 1925, the front-page headline of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram read “Klan Throngs Invade Arlington.” The article promised “the first mounted initiation ever held in Texas,” and a barbecue of “125 baby beeves” for 100,000 klansmen. The universe had other plans.

A rainstorm abruptly ended the initiation ceremony. Governor Ma Ferguson ordered the removal of National Guard horses. And the Klan called off the barbecue. Estimated final attendance, per the organizers, was just 15,000. “More than 100 cords of wood which had been placed alongside the barbecue pits became soaked with rain,” the Dallas Morning News reported, “and the pits themselves bore some resemblance to a canal.”

The Dallas and Fort Worth klaverns had planned a barbecue that would prove the Klan wasn’t dead in Texas. They proved the opposite. The klansmen went home wet and dispirited. While it likely seemed an eternity for those living through the oppression, the rapid rise and fall of the Second KKK in Texas took only five years. When the Klan tied its promise to politics, and the time came to turn the Texas government over to the insurrectionists, the electorate spoke.

In our country today, we witness Nazis marching our streets, politicians who openly despise immigrants, and preachers who act as their apologists. This story about Texas in the 1920s teaches us about what can happen when bigotry goes unchallenged. It shows how demagogues hide behind patriotism, and lure skeptics with food and drink. It’s also a reminder that people can rise up to declare political platforms built on racism and oppression unacceptable.

Daniel Vaughn is the barbecue editor at Texas Monthly and the author of The Prophets of Smoked Meat. He has eaten at over 1,500 barbecue joints, most of them in Texas.