Will the Yellow House Turn the Corner? An Atlanta building once housed a cherished restaurant before it became a magnet for the drug trade. Its next life may depend on cues taken from Louise Cantrell, an early local food pioneer.

by Max Blau

On a crisp fall evening in 2019, as the last glimmers of sun faded over Atlanta’s west side, a rare quiet fell over the intersection of James P. Brawley Drive and Cameron M. Alexander Boulevard. The blue glow of an overhead surveillance camera served as a reminder this corner once needed watching. But a dramatic change occurred in the past few months. Gone were the young men on the corner, the changing lineup of convenience stores, the handshake drugs, the flashing police car lights. The bright yellow building that defined the corner—and long fed the community—stood vacant for the first time in a generation.

Empty buildings often signal the burden of blight to follow. But to nearly two-dozen residents gathered a block away, the emptiness offered the hope and possibility of a blank canvas. A few minutes after 6:30, a sharply dressed urban planner named Jesse Wiles spoke about a unique opportunity ahead for the property known as the Yellow Store. The previous spring, the Westside Future Fund (WFF)—a nonprofit redeveloping neighborhoods in the area—purchased the building. The nonprofit hoped to spark revitalization near the two-year-old $1 billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium, home to the Falcons and United sports teams, at this once-bustling commercial node in the heart of a historic black neighborhood.

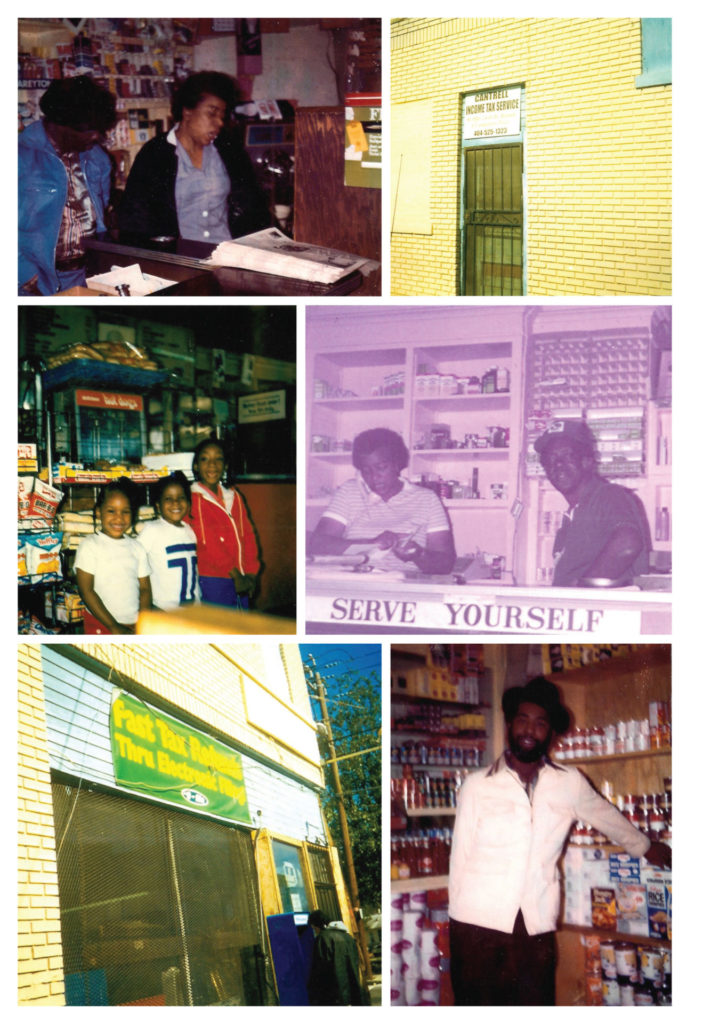

In the early 1970s, a housekeeper named Louise Cantrell opened a family restaurant there, providing soul food and a gathering spot for residents young and old. But as the forces of poverty and crime beset the neighborhood, her business slowly struggled and eventually shuttered in the mid-2000s. Her family leased the space to tenants who operated convenience stores that sold candy bars, chips, and sodas. The unhealthiest part was not what sat on the shelves. To buy drugs outside the store, people drove in from as far away as Alabama and Tennessee. During the past decade, residents who sought healthy and affordable food often had to travel outside the community to get it, if they got it at all.

As Wiles asked residents for help plotting the Yellow Store’s next chapter, activist “Mother” Mamie Moore held a stack of papers in her lap that detailed ideas for how food could play a role in the corner’s revival. Since moving to English Avenue, the eighty-one-year-old former president of the neighborhood association had fought for new parks and even the youth center that hosted the evening’s meeting. It was part of Moore’s broader effort to ensure that the WFF—and by extension the city, which along with corporate foundations pumped millions of dollars into the nonprofit—followed through on its promises to make the neighborhood safer and stronger. Her commitment stemmed, in part, from the fact that residents never forgot the city’s broken promises that the Westside would benefit from the construction of the Georgia Dome in its backyard.

Sitting to Moore’s right was a man in a blue plaid shirt who believed the Yellow Store could help rebuild trust in English Avenue. His name was Larry Cantrell, and he was the son of Louise Cantrell, who died in 2011. He never forgot how two of her key ingredients—food and community—were part of the recipe for the thriving corner. Recognizing this, Larry decided to sell the building to the WFF with one simple condition: English Avenue residents would help write the Yellow Store’s next chapter.

“[My mother] was dedicated to that building,” Larry Cantrell told me one day over coffee. “When she left, she wanted the best to come of it. She told me to make sure that whoever gets it after our family did the right thing.”

To understand the corner’s full potential, start in the early 1970s, a few years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who lived on Sunset Avenue, a short walk from the Yellow Store. During that era of progress and pain, between white flight and Black Power, Louise Cantrell made an important choice. Living in English Avenue and raising her children in Herndon Homes public housing made her want to do more than clean other people’s houses. So she and her husband, Charles, a newspaper delivery truck driver, cobbled together enough savings to acquire the nearly 6,000-square-foot building at the corner of what was then Kennedy and Chestnut streets.

The Cantrell family charted another course for a building that had long housed neighborhood pharmacies. Charles rented out rooms upstairs to tenants and opened a combined record store and shoe repair shop on the ground level. Louise oversaw the building’s anchor space, which became the family’s restaurant, Cantrell Soda and Sundries. In the darkness before dawn, Louise would slip through the front door of the two-story brick building to prep for the morning. Some customers came for just a quick cup of coffee while others sat at one of the ten or so square tables, waiting for the smell of sausage and biscuits to waft from the kitchen. By the time noon arrived, patrons sitting at her lunch counter stools would down fried chicken, collard greens, black-eyed peas, and candied yams. Georgia state lawmaker “Able” Mable Thomas remembers the thin and wide diner-style hamburgers, while others recall the chocolate milkshakes.

Over time, English Avenue residents would simply refer to Louise as Mama Cantrell. She created a comfortable and familial space that shaped memories of English Avenue, a neighborhood that, just decades earlier, flipped from white to black. Churchgoing children pocketed change from their family’s offerings so they could have something left for sweets at the restaurant. Teenage girls met their friends there before playing in the streets. Young men laid eyes on future wives there for the very first time.

Mama Cantrell raised many of her seven children in the restaurant. Larry pitched in, repairing shoes at his father’s place, working shifts behind the counter with his mother, delivering orders. “We had to work there,” he remembered. “When you get out of school, you’d come straight to work after.” Here Larry learned the power of food and the power of a beloved community.

By the late ’70s, as Mama Cantrell’s restaurant became a staple in English Avenue, she showed how small food establishments could strengthen Atlanta’s Westside neighborhoods. Like other entrepreneurs, she would soon grapple with a dramatic shift in how and where black neighborhoods in American cities secured their food. Over the course of several decades, supermarkets moved into suburbs, following the path of middle-class whites. Then, Atlanta’s suburban migration changed. That migration eventually included black middle-class families who left communities wrecked by disinvestment.

Larry Cantrell never forgot how two of his mother’s key ingredients—food and community—were part of the recipe for the thriving corner.

Black food entrepreneurs in Atlanta and beyond sought to shore up food access following the flight of supermarkets. A wave of black entrepreneurs opened grocery stores in cities such as Columbus, Ohio; Washington, DC; and Buffalo, New York, according to Ashanté Reese, author of Black Food Geographies. Along the southern edge of English Avenue, Shoppers Supermarket sold fresh meat, dairy, and produce. Mama Cantrell stocked beans, grits, and other household items.

“There was self-reliance,” said Bishop John Lewis, III, an activist who grew up in English Avenue and now lives a few blocks south in the adjacent neighborhood of Vine City. “The things one would need in a community were all there. It didn’t necessitate one having to leave your area to go to areas that weren’t fully integrated.”

In the ’80s, as the Reagan-era recession and the crack epidemic rocked America’s inner-city neighborhoods, English Avenue’s remaining residents fell deeper into poverty. The hollowing of its middle class and the purchasing power that came (and left) with those residents hit neighborhood businesses. The Cantrells first closed their shoe repair and vinyl record shop. Mama Cantrell, who managed to keep the restaurant afloat, still fed English Avenue residents regardless of their financial status. If someone she knew couldn’t pay the full amount for a three-piece fried chicken dinner, she’d give that person two pieces for half the price.

In the ’90s, business slowly declined at the Cantrell family restaurant, particularly as the neighborhood’s drug trade boomed, transforming the community into the Southeast’s largest open-air market for heroin. Then came the death of Mama Cantrell’s husband, Charles. Despite this, Mama Cantrell, then in her sixties, kept going until she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2005. Focused on her health, she closed the restaurant down and asked Larry to watch over the building until she got better. In a neighborhood where nearly half the houses were vacant, Larry believed that the building should be occupied. It was also the practical choice: Another tax bill would arrive soon.

Renting out the building was no easy feat. The Brawley Drive corridor further declined after the turn of the millennium. Abandoned lots were as common as the unsafe slumlord apartments. Even Mama Cantrell expressed worry about the growing drug trade but kept her head down for the restaurant’s sake. Despite the limited options for tenants, Larry eventually found businesses to house in the space.

The blight, along with the drug trade, slowed foot traffic into the store. As Joan Vernon, former president of the English Avenue Neighborhood Association, explained, “That intersection was owned by the locals. If you weren’t a part of their crew, you weren’t going in the store.”

Those who went inside found little, if any, fresh and affordable food. Like other black neighborhoods in American cities, corner stores increasingly became the only grocers. They often had generic names. On the east side of Atlanta, the Edgewood neighborhood had the Red Store. On the south side, the Pittsburgh community had the Pink Store. Many of those convenience stores prioritized food that was cheaper and full of empty calories instead of produce that grew for months and meals that simmered for hours.

Many studies outline the consequences of insufficient access to healthy, affordable foods: higher rates of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes, along with lower life expectancies. Fewer discuss the systematic racism underlying those food systems. A study published by the University of Nevada at Las Vegas found that black neighborhoods were only half as likely to have a supermarket as white neighborhoods. “It’s not simply an issue of poverty,” Johns Hopkins researcher Kelly Bower told the Los Angeles Times in 2013. “In fact, a racially segregated poor black neighborhood is at an additional disadvantage simply because it is predominantly black.”

When I asked Larry about why he chose to rent to convenience store operators, he spoke with slight regret. “I thought it was good at first.” Ultimately, he believed his first priority was to save the building—and that meant having a reliable rent check every month to offset the taxes.

In 2012, after turnover in tenants, he rented to Yaril Grocery, a business owned by Nazreat Weldeyohnnes. As Larry learned, the groceries were only different in name. Yaril’s presence did little to slow the crime on the block: From 2012 to 2017, Atlanta police officers wrote up more than 100 incident reports. Nearly a quarter of those were for drug possession, assaults, and robberies near the Yellow Store. In 2018, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation made arrests inside the store for alleged illegal use of gaming machines.

Residents saw the Yellow Store in new ways. Several called for the Yellow Store to be demolished and replaced with a new grocery. Larry was torn. He didn’t want to see Mama Cantrell’s legacy—and her building—erased. But something had to change.

“That intersection was owned by the locals. If you weren’t a part of their crew, you weren’t going in the store.”

In January 2019, Larry received a letter from the Westside Future Fund. They wanted to discuss buying the Yellow Store. He agreed to discuss it with their real estate team.

The WFF, founded in 2014, was still trying to prove itself as a trustworthy partner in English Avenue. If neighborhoods are the sum of promises kept and unkept, and of plans executed and shelved, current and former English Avenue residents had every right to be guarded about the plans of a nonprofit with deep ties to Atlanta city government. Official efforts to improve conditions, in decades past, did not make progress. Aside from an occasional initiative promoting healthy eating, food access did not improve in the neighborhood.

No one understood this better than John Ahmann, a political operative tapped by former mayor Kasim Reed to lead the nonprofit. As WFF president and CEO, he had his own ideas about how to revive the west side. Instead of acting on those ideas first, he directed WFF to view community residents as experts when defining community needs.

On May 24, 2019, Larry sold the Yellow Store for $600,000— a discount, he says, compared to what he might have eventually received from a private developer. By the start of summer, Ahmann kicked out Yaril Grocery and temporarily offered the space to Westside Blue, a security force of off-duty police officers, to stabilize the corner. Then he reached out to Wiles, the urban planner, who previously led a public effort to create the Westside Land Use Framework Plan, an official city document intended to guide Westside community redevelopment without displacing legacy residents. At the late October meeting, Wiles wanted residents to add to this plan by sharing their dreams for what should replace the troubled grocery space.

On the other side of the room, Wiles’ team set up blank poster boards, where residents could offer new ideas and rank their preferences. Residents were asked: “If you have a magic wand and could do anything with the building, what would you do?” The answers were as varied as the Cantrell family’s original businesses: Art gallery. Hair salon. Cleaners. Game room. But the majority of those cards, from a produce market to pop-up restaurants, reflected the community’s desire for a stronger, healthier local food economy.

If neighborhoods are the sum of promises kept and unkept, English Avenue residents had every right to be guarded about the plans of a nonprofit with deep ties to Atlanta city government.

“The neighborhood needs a gathering place,” said Mother Moore as she looked at one of the boards. “People need to understand the economics of what we select. For example, a bakery itself may not work. … But a coffee shop may work.”

A few weeks after the Yellow Store meeting, I chatted with Larry Cantrell at a coffee shop between English Avenue and his home in Ellenwood. We revisited some of the initial suggestions offered by residents. As we talked, I mentioned that one of the ideas I heard gain support was a small grocery that could serve multiple roles in the community. We were meeting in a building that functions that way. Community Grounds, the only coffee shop in the South Atlanta neighborhood, shares an address with Carver Neighborhood Market, a 2,600-square-foot grocery store that sells fresh-baked breads, affordable seasonal vegetables like squash and eggplant, and organic milk from a South Georgia dairy farm.

Larry looked around. Holding his coffee, he looked my way: “I’d like to see something where people can come and eat, buy food, and buy lunch,” he said. “Something similar to what was there. I’d like to see something that would benefit the neighborhood.”

Max Blau is an Atlanta-based journalist who reports on health care, criminal justice, and environmental issues in the South. His work has been published at The Atlantic, Politico, and The Washington Post.