THE ONE TRUE PITMASTER Ricky Parker, like his barbecue, contained multitudes

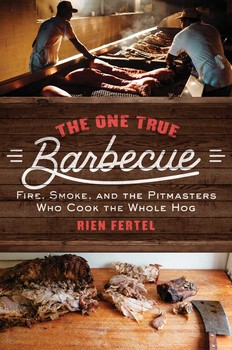

From The One True Barbecue: Fire, Smoke, and the Pitmasters Who Cook the Whole Hog by Rien Fertel, Copyright (c) 2016 by Rien Fertel. Reprinted in Gravy, Spring 2016, by permission of Touchstone, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Photos by Denny Culbert.

A DYING BREED

Ricky couldn’t say for sure how many hogs he’d prepped since 1976, when he began tending the pits at Scott’s Barbecue, the year Early Scott took the thirteen-year-old boy on as an apprentice and, eventually, son. It was immediately clear to Scott that no one could smoke hogs like Ricky. He was a pitmaster, body and soul, born to the rough trade. He would master pit, fire, and hog. Shovel, sauce, and spice. He would master barbecue. The young Ricky could remain on his feet for twenty hours straight: cleaning the pits, stoking the fire, shoveling coals, smoking hogs, serving customers. And the customers liked Ricky: courteous, handsome, a bit wild. Dedicated to finishing the job and doing it well, Ricky would eat standing up—“I eat on the run,” he liked to say—and rarely if ever slept for more than three hours a night. Sleep didn’t come easy when you were cooking with live flame. He’d close his eyes and experience terror-filled dreams of his pit catching fire, his hogs rendered inedible, the Henderson County Fire Department arriving too late to save his smokehouse, which now lay a conflagrated heap of charred timbers and sheet metal. Ricky would rather stay awake to watch the fire.

His eating and sleeping patterns, or lack thereof, remained constant through the summer of 2008, when I first watched Ricky Parker smoke a pig. At first sight of him—slender and gangly, his skin bronzed from working in close quarters to fire—I questioned how he could possibly find time even to dress himself, energy enough to shave that perfectly sculpted Van Dyke beard. Three hours of sleep and working like this? How can he be standing? How can he be alive?

But Ricky assured me that this was all part of the whole-hog pitmaster’s life. He repeated a boast that he recited to just about everyone who came to interview him: “I got to buy four or five pair of shoes a year. I do a lot of walking, a lot of pacing.” He told me that he was married to his work more than he was to his wives, past and present. He spoke in self-mythologizing tones. He was special, an original, a dying breed. For all he knew, he was the last of the great pitmasters, a man who strove to smoke as many hogs as humanly possible.

Ricky counted sleep in hours and shoes in pairs, but, above all else, Ricky counted his life in hogs.

Annually, beginning with my first visit in 2008, I’d make a pilgrimage to eat Ricky Parker’s barbecue. Each year, as I ate my chopped pork sandwich, he’d tell me about a future date circled on his mental calendar: July 4, 2013, the holiday weekend over which he aspired to cook one hundred whole hogs. One hundred! Hardly an arbitrary number crudely culled from a beer-fueled backroom bull session, but the apogee of human achievement. The age of modern Methuselahs. In sports, the most notable of statistical achievements. One zero zero. A symbol of perfection. One hundred pigs. One pitmaster’s dream. Three digits’ worth of whole hogs. A century of swine.

Ricky Parker knew with some certainty that no pitmaster, living or dead, had ever reached that number. Through a complex formula of weather data, gasoline prices, hog futures, and unemployment rates, Parker calculated that 2013 would be his year. He could stop counting hogs after this achievement. He could slow down, ease into retirement, pass the pitmaster’s shovel off to his son Zach. He might even learn to sleep.

But until then he would keep on cooking. Because no one could smoke hogs like Ricky. No one worked to make barbecue like this anymore. Few cared like Ricky Parker, the world’s greatest pitmaster, the man who counted hogs to keep both himself and barbecue alive.

THE BALLAD OF RICKY PARKER

The whole hog is the perfect blend of barbecue: Every little bit of the animal can be consumed in a single, decadent, maybe even gluttonous bite. “You got a little bit of everything,” Ricky Parker liked to say. Ricky gave the world his all by providing everything the pig had to offer. This is what made the offerings of Scott’s Barbecue distinctive: this everything, the very wholeness of whole-hog barbecue itself.

Ricky Parker’s menu offered two sizes of wax-paper-wrapped sandwiches— regular and jumbo—alongside barbecue sold by weight (priced at $7.50 per pound when I first visited) and stuffed into a paper tray decorated in red and white gingham. Ordinarily, the meat arrived cleaver-chopped to a medium coarseness. But whether delivered by bun or tray, the barbecue could be ordered crudely hacked, finely minced, or pulled, straight no chaser, from the hog.

Depending on one’s tolerance for heat, the barbecue could be dressed with sweet, mild, medium, and hot homemade sauces, all made fresh by Ricky Parker. Most locals ate their sandwiches topped and dripping with coleslaw, which came in two varieties: the standard mayonnaise-heavy version, called white slaw, and a red variant made with ketchup and vinegar. Sandwiches could be further tricked out with fat rings of raw Vidalia onion.

“He served five, ten, as many as two dozen hogs a day, every day but Sunday.”

Scott’s sold a few varieties of potato chips and often stocked some fried pies made by a John Gordon from his house up the road, but there were no other sides except baked beans, which were burdened, in the best way possible, with heapings of barbecued pork.

Smoking whole hogs allowed Ricky to provide eaters with any edible portion of the pig; in addition to portion sizes and spice levels, customers, as if peering through the window of a butcher shop’s display case, could select their individual cuts to get the taste and texture they wanted. At Scott’s, one could eat a different barbecue sandwich every day of the week. The combinations and permutations were near limitless.

For example, a customer could request the wetter, fleshier meat from the inside of the shoulder, or the crusty exterior bark charred by flames. One could go even deeper, literally, into the very heart of the pig, to demand the meat from the undersides of the ribs, or the rib bones themselves; the jowly flesh nearest the neck, or the delicate tenderloin. Cuts could be mixed and matched—a pulled part from this, a chopped bit of that—to imagine the perfect sandwich.

Over a ten-minute stretch perched at Scott’s lunch counter one summer afternoon I witnessed the full range of possible orders. Through the Plexiglas window that separates the meager prep area from the dining room, customers shouted rapid-fire lists of ingredients and techniques, combinations that ranged from the mundane to the extraordinary, the unusually healthy to the distressingly heart hazardous.

A quarter pound of plain barbecue, please.

Regular barbecue, white meat, extra chopped, no fat.

Jumbo, dark, pulled with a lotta fat on it, mayo slaw, extra hot. Occasionally, a customer would drop terms that reminded me of the so-called “secret menu” at In-N-Out Burger, a West Coast fast-food chain where a rabid fan base fetishizes an in-the know language of keywords and food hacks. At Scott’s, these orders sounded foreign, like they could not possibly come from a pig.

A medium middlin’. Or, even more bizarre: You got any catfish today?

“Smoking whole hogs allowed Ricky to provide eaters with any edible portion of the pig. At Scott’s, customers could eat a different barbecue sandwich every day of the week.”

Middlin’ is what most people commonly refer to as bacon, the fatty underside of the hog, which earned its vernacular nickname for its location at the animal’s midsection. The catfish is a rarer cut of swine, a six-by-three-inch strap of meat embedded under the tenderloin with the shape and fleshy shade of a catfish fillet and arguably the most tender part on the hog, a dozen times more succulent than the meat from those fishy mud dwellers for which it is named. Because a pig only yields two sandwiches or so worth of this cut, customers were known to leave Scott’s empty-handed and hungry if they couldn’t fulfill their catfish fix.

But there would always be another opportunity for a bite of catfish tomorrow, another shot at the big score. Or the next day. Or the day after that. Or never, if you didn’t ever arrive early enough, say well before the noontime surge. “Root, hog, or die,” the adage goes: fend for oneself, fight for sustenance and survival, or starve. There are only so many parts on a pig, only so much barbecue in a whole hog. Root, hog, or die.

Ricky Parker stood slight of frame. Lanky and rail thin, he looked no larger than the hogs he lifted each morning onto his pits. But the pitmaster, like his barbecue, contained multitudes.

Ricky defined his own mythos. To hear him tell it, his life resembled an as-yet-unwritten country and western song: “The Ballad of Ricky Parker.” And though he didn’t like to sit down and pore through the particulars of his life, once he began spilling his own history, he would talk like he walked: fast and out of control. I never knew which of his stories to believe—dates changed, details popped in and out of each telling. It became clear that the trauma that went hand in hand with hard living was a matter of course.

He was born in Memphis in 1962, to a migrant farming family that crisscrossed the country with the seasonal harvests. Joe and Callie Parker dragged their five children from apple orchards in Michigan to wintertime Florida orange groves and back again. Ricky remembered picking fruit with his sister and three brothers for a few hours before the opening school bell rang and returning to the fields after class. He was bred to work, he told me, born to run. The family settled in Lexington, Tennessee, the seat of Henderson County, an agricultural town situated exactly halfway between Nashville and Memphis along Highway 412. At the age of thirteen (sometimes he said sixteen), Ricky walloped his old man with a baseball bat while defending his mother from another round of liquor-fueled abuse. Ricky returned from school the next day to find his belongings on his family’s front porch. He escaped across town and took what jobs he could get: bagging groceries, mowing lawns, pumping gas.

At the Morgan’s Service Station he was discovered by Early Scott, a former school bus driver who fifteen or so years earlier traded a pair of yellow buses to his brother for Scott’s Barbecue. Scott was a rowdy man, a man with a thirdgrade education who was driven to drink and prone to violence and bizarre behavior. He once sliced a man clear across the belly for attempting to steal a twenty-five-cent bottle of Coke. Because he did not believe in banks, he’d absentmindedly bury jars full of cash—fifteen thousand here, twenty thousand there— around his barbecue restaurant’s property and would often resort to hiring guys with metal detectors to root out the mislaid loot. Still, Scott was an honorable man to work for. A man with no children of his own who might have been searching for a son to take over his barbecue business. “It’s time to put the boy to work,” Scott told Ricky’s dad, who, after the beatings and neglect, was still the boy’s father. And Joe Parker complied. No one said no to Early Scott. Ricky grew up a typical child of the 1970s. He loved karate and was known to be an eight-wheeled speed demon at the roller rink. A photograph from the era shows Early Scott, portly and proud, grouped with his wife, Dorothy, and two unnamed workers posed in front of his restaurant. All four smile for the camera. Off to the left side, separated from the group, Ricky, wearing those oversized, tinted early eighties–style lasses, looks uncomfortably shy. He stands with his hands pressed deep into his pants’ side pockets as if he could find some deeper truth hidden there.

This photo was taken before he grew out his signature Van Dyke beard. Before he started smoking Swisher Sweets cigars. Before the marriages, kids, and divorces. Before the obsessive work hours. Before being the man he would become, he worked nights and weekends at Scott’s Barbecue, an assistant in the pit house, while attending Lexington High. He couldn’t try out for the baseball or basketball teams, missed just about every party, and couldn’t score more than a second date because he did nothing but sweat and toil for Early Scott. He quit school just three months shy of graduating. It was then that Scott, his mentor and adopted father, told Ricky that he had learned enough about learning. Now he would learn about life.

But birth fathers are hard to forget and even harder to forgive. Ricky installed the same baseball bat that he used to whoop his dad and win his freedom on a wall of the pithouse, visible only to him, where it would hang as a totem, a mythological reminder of what came before. It was as if he were the reincarnation of Sheriff Buford Pusser, the Tennessee lawman made famous in the Walking Tall films, who patrolled McNairy County, just thirty miles from Lexington, often fighting vice and crime with just the aid of a baseball bat. Over time, saturated by years of smoke and grease, Ricky’s own bat would turn from its natural ash-wood grain to a lustrous black, like a shoe polished to a mirror’s sheen, so glossy that it appeared to glow amid the darkness of the pit house.

A first-time spectator could mistakenly judge Ricky’s hog-cooking method to be as simple as throwing fatty meat on a fire. But just an hour in his smokehouse made it clear that Ricky’s apparent primitiveness was as deceptively simple as the three-chord blues. From the sow’s litter to the crafting of his sauces, Ricky had systematically mapped and quantified every step of the process.

Unlike just about every barbecue establishment throughout the country, whole hog or not, Ricky did not buy his pigs at market or barn sale. He didn’t rely on a packing company to deliver his meat by refrigerated truck or run down to the local slaughterhouse and say, “Gimme a two hundred- pound hog.” Ricky knew his hogs from the moment they were born.

I asked him what kind of hogs those were.

“Pacific pigs,” I heard him say.

“Pacific pigs?”

“Pah-cific pigs.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: He imported his hogs from the West Coast? Maybe whole hog wasn’t so locally defined.

“Where do you get them?” I hesitated. “California?”

Ricky rolled his eyes and repeated what he’d been saying this whole time, but now really vocalizing that first S sound: “Spah-cific.” It turned out I was just dumb, unused to hearing Ricky’s vibrant West Tennessee accent.

“I’ve got a certain type of boar and a certain type of gilt,” he explained as if illustrating the birds and the bees: one pig prized for his muscle content, another for her fatty marbling. Together with his trusted hog farmer, Roger Gill, Ricky had tinkered with the genetic makeup of his hogs until settling on a half-Duroc, half-Yorkshire breed that delivered a rather lean 3 percent fat content—thus providing the optimum yield of sellable meat—while still furnishing a sufficiently blubbery three-quarter-inch fat cap along the hog’s back. Ricky’s careful consideration of hog anatomy was a thoughtful reaction against the historical entanglements of the American hog industry. Three decades earlier, when he began working in the pit house under Early Scott, barbecue-ready hogs weighed in with a 10 percent fat content. But since 1987, the National Pork Board began marketing their product as “the Other White Meat,” fulfilling nationwide demand for a more flavorful alternative to chicken and turkey, while keeping the cholesterol levels at a minimum. To sate the consumers’ demands, commodity farmers and wholesalers genetically reengineered the American hog to achieve a fat content nearing zero. Whole hogs became more wholesome.

The average Roger Gill–farmed hog weighed in close to the 300-pound range when nearing only its sixth month on the planet Earth. A quarter or more of that total live, or “on the hoof” weight would be lost on the slaughterhouse floor, with the removal of the internal organs and head, leaving a carcass with a “hanging” or “tag” weight of approximately 200 pounds. Edible meat constituted about 70 percent, or 150 pounds, give or take, of that carcass, minus the skin, bones, and cartilage. But that raw flesh, its protein-packed cells brimming with water and other liquids, would literally boil off most of its weight throughout the long cooking process. Thus the original tag weight would yield only 30 to 40 percent after roasting, or about 70 pounds of sellable meat. Other whole-hog pitmasters made do with smaller pigs, often tagged in the 150-pound range.

I asked Ricky what it took to reverse engineer his pigs to get to that 3 percent fat yield that made them so marbled, meaty, and colossally grand. “Well, that I can’t say,” he politely demurred, before implying that it was a secret blend of supplements added to the hogs’ cornbased diet that packed on the pounds.

He was more forthcoming with most other aspects of his trade. Only hickory wood heated his pits: skinny three-footlong planks—tossed-off barrel staves, I would come to find out—that he bought from a sawmill in nearby Savannah, Tennessee. It took just over half an hour to burn a four-by-six-foot pile of hickory planks down to coals and ash, ready to heat the hogs. He used a long-poled shovel to scoop the incinerated hickory from the fire pit, just steps outside the smokehouse, and deposit layer after layer of the fiery fuel source under the hogs, all the while making sure to disperse the embers flat and even across the pit floor.

Those pits looked like most any other I’ve come across: a simple cinder-block construction, built waist high and running the length of the room. Inside the two rows of pits, thick steel bars, spaced every six inches, formed a latticework to hold the pigs over the void. He insulated the top of the pits with vast sheets of corrugated cardboard, like refrigerator boxes but sturdier, thicker, and heavier, that he had made to order from a container manufacturer down the road. After exhausting every last ember from the fire, he’d begin to cover the pits with the corrugated slats, none of which was large enough to completely cover a single pit, so he’d arrange them, layer upon layer, to form a sort of jigsaw puzzle made from cardboard sheeting. When finished only faint whispers of smoke escaped, coiling around certain joints and corners among the tangled mass of cardboard. Though he had no thermometer with which to measure, he knew that the pit’s internal temperature would hold steady at around 225 degrees.

Those pits looked like most any other I’ve come across: a simple cinder-block construction, built waist high and running the length of the room. Inside the two rows of pits, thick steel bars, spaced every six inches, formed a latticework to hold the pigs over the void. He insulated the top of the pits with vast sheets of corrugated cardboard, like refrigerator boxes but sturdier, thicker, and heavier, that he had made to order from a container manufacturer down the road. After exhausting every last ember from the fire, he’d begin to cover the pits with the corrugated slats, none of which was large enough to completely cover a single pit, so he’d arrange them, layer upon layer, to form a sort of jigsaw puzzle made from cardboard sheeting. When finished only faint whispers of smoke escaped, coiling around certain joints and corners among the tangled mass of cardboard. Though he had no thermometer with which to measure, he knew that the pit’s internal temperature would hold steady at around 225 degrees.

Without having sat through a single physics class, he could more than untangle the basic principles of thermodynamics, atmospheric pressures, and beyond, without the benefit of timers, thermometers, or other instruments. He called this common sense, but few pitmasters have ever understood the science behind barbecue like Ricky Parker. He could explain the insulation strengths of cement blocks versus corrugated cardboard; expound on the occurrence of air pockets and drafting within his barbecue pits, and their effects on smoke; and illustrate how dips and surges in external temperature, humidity, or precipitation would affect the time it took to produce a perfect piece of meat.

“If each of us on the planet Earth is capable of something greater, imbued with and defined by an extraordinary talent—a superpower, even—that allows us to achieve something bigger, this was Ricky’s: the ability to oppose the slowness of time.”

But there was another tool, an unquantifiable know-how, in Ricky’s pitmaster skill set: patience. Despite his limitless energy levels, the pairs of shoes he wore out each year, and the number of hogs he’d cook over a lifetime, Ricky’s livelihood was defined by a capacity to ease, and never rush, his hogs to doneness. If each of us on the planet Earth is capable of something greater, imbued with and defined by an extraordinary talent—a superpower, even—that allows us to achieve something bigger, this was

Ricky’s: the ability to oppose the slowness of time. When watching Ricky, it was almost as if the faster he ran, the quicker he hustled about the pit house, the slower the minutes turned to hours and dusk turned to dawn. His hogs might have cooked for sixteen, eighteen hours in real time, but in Ricky time those hogs might have been immersed in smoke and heat for twice that amount. He could do the work of four men, could squeeze two evenings into one, and could coax more smoke out of a piece of hickory wood—one day he might even fit one hundred hogs into a weekend!—but he would never tire, never lose patience.

This is what made Ricky a true master of the pit.

RICKY PARKER BUILDS A LEGACY

I often questioned what attracted me to Ricky Parker, what compelled me to return year after year, summer after summer to Lexington, Tennessee.

There was the barbecue, of course, which I felt myself hunger for, my belly aching with emptiness, each spring when the weather warmed, the outdoors blossomed with fresh possibilities, and the open road beckoned. The cravings rumbled awake in early April, when the hardware stores stacked bags of charcoal high enough to resemble a monolithic shrine to the backyard gods. When meat-scented smoke perfumed the air in public parks and, especially in my home city of New Orleans, outside of bars, where enterprising grillmasters cooked from the back of their curbside pickups. This is when the world, my world, began to smell of barbecue.

By May, when I began counting down the days until the semester’s end, I’d start planning a road trip. Could I wait until July, or would I hit the road as soon as I turned in my final paper? Would I drive up to Memphis and stay with friends for a night or take the straight shot to Lexington, shaving fifty miles off the total distance and ensuring that I would make Scott’s by nightfall? But Ricky would have sold out of barbecue by then. He usually extinguished his pits, locked the doors, and hung the sold out sign from the window by four p.m., sometimes hours earlier.

I often stayed at the Econo Lodge, a shabby motel that sat directly across the highway from Scott’s, with an ancient blue-haired lady behind the counter who rented rooms at fifty-five dollars per night. In the mornings I could wake up with the sun, walk outside, and smell fresh barbecue. Before heading over, I’d pick up coffees and a sack of biscuits and hash browns from McDonald’s to share with Ricky and his sons—a bribe of sorts to cajole them into letting me hang around the pit house until the hogs were done. I’d stick around until lunch, then order a pound of barbecue: a heaping of chopped shoulder mixed with a handful of its crusty, exterior bark and with a pull of middlin’ on top.

So I traveled up to Lexington each year to sate my hunger for another plate of barbecue, but I also went to satisfymy curiosity about Ricky Parker. What info could I glean this visit? Would he, as usual, be too busy to talk? Was he still shooting for one hundred hogs? How in the hell did he continue to do what he did? Knowing Ricky’s work ethic—the hours he put in, his obsession bordering on pathological—I recognized that he wouldn’t be cooking hogs forever. He was nearing fifty years old. He said he was slowing down, that he used to run but now walked. Men didn’t live to work much longer if they worked like Ricky did, though to me, it still looked like running.

I turned friends and family on to Scott’s so they could share in my love for the barbecue, but also so that they might update me on the status of its pitmaster. He still cooking? How’d his barbecue taste? Like me, my stepfather, Danny, took time to make the stop each year. He remember me? Ask about me? I’d question other barbecue enthusiasts, many of them longtime fans of Ricky’s, who’d just returned from their own road trips to West Tennessee. How’s his health? How’d he look?

Whispers spread by friends and Scott’s devotees, facts or fictions—it was hard to distinguish between the two when it came to Ricky. Ricky had cornered the local swine market to ensure that only he could get his hands on a fresh hog. Ricky was in jail. These were the updates I needed to hear—Ricky had his obsession, and I had mine. Ricky had curbed his drinking. Ricky was drinking again. Ricky had switched from Jack Daniel’s to vodka because it sat better in his stomach. But I often couldn’t bear to listen; it seemed his life was spiraling downward. It wasn’t alcohol but something else. Ricky didn’t look right, didn’t sound right, didn’t act right. That barbecue ain’t shit.

But no matter the talk while I was away, each summer I’d return to Lexington and Scott’s and find Ricky just where I had left him. In the pit house, holding his shovel, or behind the counter, sliding the glass window aside to shake my hand before taking my order and shouting it over to Zach or Matt: “Pound of barbecue, hot!” There he was.

There was Ricky Parker.

If every spectacle includes and concludes with an explosive ending, the climax of Ricky’s whole-hog cooking was the “flip,” that final moment, after twelve or more hours of cooking, when with a heave and heft he flipped each hog so that the outer, or skin side, of the whole beast was rotated upward to earthward revealing what had long remained hidden: what was once a fleshy pink corpus transformed into a beautiful mess of slightly charred rib bones protruding from a ruddy-gold mass of roast meat.

Whether by hand-cranked spit or engine-spun rotisserie, the heat source for roast meats needs to be distributed evenly to ensure a well-cooked pig, side of beef, whole fish, or what have you. Think of the perfectly toasted marshmallow, its caramelized surface achieved by twisting it over the campfire; without motion, the marshmallow will burn unevenly, blacken, and might even combust. But a whole hog is not a marshmallow. Two-hundred-pound pigs are much too heavy, too bulky to reliably turn on a spit. Conceivably, a pitmaster could rotate a hog every hour or two, but the energy involved in hefting the carcass up and over, anywhere between four and twelve times in a cooking cycle, within arm’s reach of fiery coals, as the meat becomes hotter to handle and increasingly grease slicked with rendered fat, would make the endeavor unbearable. Multiply that by twenty hogs all cooking at once, and even the most vigorous of pitmasters is faced with an impossible task.

For anyone who’s turned even a spit full of chickens over a roaring fire, the work becomes quickly monotonous and tiresome. Before the modern-day mechanization of the rotisserie, turnspit dogs kept meats slowly rotating over the open fire. In the sixteenth to mid-eighteenth centuries, throughout Britain and its colonies, including America, households might have owned a Canis vertigus, Latin for “dizzy dog,” a specific breed raised to run in a wheel— like those favored by hamsters—which spun a chain connected to a fireplace spit. Also called kitchen dogs, cooking dogs, underdogs, and the Vernepator cur, or “the dog that turns the wheel,” these short-legged, long-bodied Sisyphean pups also worked in early New England sculleries. The cruel treatment of the turnspit dogs eventually fell out of favor, and helped lead to the formation of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and the Canis vertigus became extinct.

Luckily, for the sake of mutt and man, pitmasters long ago figured out that whole hogs did not need constant turning if they remain belly, or meat side, down. Well-insulated pits, hardwood coals shoveled at timed intervals and deposited consciously around the carcass’s perimeter, and vigilance against flame and flare-ups will keep a pig evenly heated, its meat uniformly browned. But eventually all hogs need to be rotated, flipped upward so that the meat can meet its maker and greet the world as barbecue.

“One by one, day by day, across thirty-five years, Ricky Parker flipped hog after whole hog. I attempt to total the numbers but my head spins dizzily just thinking of Ricky: our Vernepator pitmasterus, the man who spun the wheel.”

Ricky Parker, naturally, had his flip technique systematically diagrammed, a series of steps from which the pitmaster and his pit hands would never deviate. First, he needed to determine that a hog had been cooked through to doneness. Tenderly squeezing its thick, round hams, like a doctor probing for foreign bodies, he could feel if the skin had separated from the flesh underneath. It felt, to me, like handling a slightly deflated basketball: applying a bit of pressure formed an indention that would snap back into shape when released. He then enveloped the hog’s outer upturned skin with a single layer of tinfoil. A steel grate, the exact same lattice-type framework that held the pig on the pit, was placed atop the now foil-topped hog. Ricky then tightly fastened these two grates together with strands of wire, sandwiching the hog in between. With a great inhale and flexing of biceps, he hoisted this massive hog sandwich up and toward his chest, using the bars of the pit’s grill to guide and glide the bottom-most grate, before pushing out and, releasing his weight to gravity’s fortunes, upending the hog to land belly up.

One by one, day by day, across thirty-five years, Ricky Parker flipped hog after whole hog. I attempt to total the numbers but my head spins dizzily just thinking of Ricky: our Vernepator pitmasterus, the man who spun the wheel.

Ricky Parker had met the enemy and it was a stainless-steel box, the size and shape of a pool table, a closed-lid oven big enough to fit a whole hog, with four legs on wheels for added mobility, in case one needed to roll it closer to any 240-volt electrical outlet.

A product of nearby Jackson, Tennessee, this contraption went by the generic name Hickory Creek Bar-B-Q Cooker—though there is no Hickory Creek anywhere on this side of the state. This was the very latest in smoking technology, a modern marvel that promised to take the work out of barbecue, and it was everything Ricky hated. Within a half-hour’s drive of Lexington, I had met several pitmasters—though you could hardly still call them that—who switched from wood-fired pits to these metal monsters. One demonstrated that his Hickory Creek took just two sticks of hickory, one inch square by ten to twelve inches long, incinerated in something called “smoke tubes,” to cook an entire hog overnight. Another lifted the hood to his cooker like we were going to inspect the horsepower of his car’s engine—there were streaks of grease here and there, but it still looked sterile, antiseptically clean. He boasted that his cooking process now consisted of loading his meat into the oven, setting the time and temperature controls, and pushing a button before going home to laze around, sleep through the night, and never have to worry about a pit fire again. Fourteen hours later, his barbecue would be ready for serving. He assured me that his customers still supported the business, and he now made more money doing less work since converting to electric power. He closed the hood, and in the metal’s mirrored shine I recognized my reflection and the look of gloom that shaded my face.

I asked Ricky if the Hickory Creek salesman had visited him. “He calls me quite often. And he tells me I need one of these things, where I can go home and get some rest. And I told him, ‘What am I going to do? I’ll be bored.’ But he always calls me.”

Ricky, like his fellow whole-hog traditionalists, might stick to doing the same thing—cooking with the same wood and spicing with the same sauce—that the men who trained him did, but he would never be bored. He might remain unchanged, a diehard, a pig-headed classicist, an adherent to his swinish orthodoxy, but Ricky did not do boring. “This place ain’t never changed,” he told me, and he planned to run his business that way until the day he died or was forced into retirement.

“If they made me quit cooking with wood, and I couldn’t buy whole hogs,” Ricky liked to tell anyone who questioned his future in the business, “I would totally quit.” He, like many whole-hog proprietors, took pride in the grandfather clauses that protected their pit houses from ever being shut down by the local fire chief. But few acknowledged that the whole whole-hog business model is one big grandfather clause, an accumulation of provisional exemptions frozen in history despite the passing of time. Whole-hog stalwarts must keep their menu short and simple; operate in a rural area, which helps in keeping labor costs and menu prices low; and, perhaps most fundamentally, have the good fortune of inheriting the establishment, customer base, and several lifetimes of experience from a family member.

But Ricky was a smart man. He wanted to leave a legacy behind, something for his five children, two of whom, Matthew and Zach, had been helping him at Scott’s Barbecue since about the time they could walk. He understood that the vast majority of his sweat and toil went up in smoke each day. He recognized the need to be remembered, the desire to be great.

In November 2005, he accepted an invitation to smoke two hogs at the Culinary Institute of America’s eighth annual Worlds of Flavor event held on their Napa Valley campus. His barbecue would be featured alongside the traditional cuisine of cooks and chefs as farflung as Oaxaca, Istanbul, and Bangalore. Though he needed a whole lot of Wild Turkey to calm his jitters, his barbecue and easy charm impressed the palates and spirits of the culinary jet set.

The next year, he traveled up to New York for the Big Apple Barbecue Block Party, an affair on its way to becoming the nation’s premier smoked-meat showcase. It was here, at a documentary short film screening that featured the pitmaster, where I first met Ricky, a full two years before I would travel to Lexington for his barbecue. That afternoon, I watched as he smiled at his own face projected on the pull-down screen and laughed as the audience laughed along with his countrified turns of phrase. At the Q&A that followed, someone asked Ricky about his first impressions of the big city. “Well,” he said, “this morning I was standing on the street outside my hotel, smoking a cigar and drinking a coffee, when someone tossed a quarter into my cup. They thought I was homeless.” Nerves soothed from his earlier experience in the culinary spotlight, he was ready to bring Tennessee whole hog to the masses. But the barbecue was not to be. The fire chief patrolling the event quashed Ricky’s plan to cook over an open fire.

When I made my first pilgrimage to Scott’s Barbecue in the summer of 2008, Ricky had renounced any ambitions of making it big on the national barbecue circuit in order to focus on his business at home. Contrary to his dedication to never changing a thing, he had recently completed construction on a new pit house—a great temple of a building—to replace the outdated and cramped shanty of a smokehouse that Early Scott had built decades before. Ricky’s pit house remains the grandest in size and scope that I’ve ever seen, with cathedral-tall ceilings, twin rows of brick pits spanning the length of the room (about forty by ten feet), a built-in meat locker, and, something I’ve never since come across, an entire side room dedicated to sauce production. The following year, he would make an even more momentous change by adding his name to the marquee out front. Twenty years after purchasing the business from his adopted pitmaster of a father, Mr. Early, Scott’s would now be known as Scott’s-Parker’s Barbecue.

It was a tongue-twister of a name, sure, but one befitting the two men who had worked to keep whole hog alive in West Tennessee.

With these changes, the new pit house and new name, Ricky was more than cementing his legacy; he was building a birthright for his children, especially his two eldest sons. Born just over a year apart, Matt and Zach were both skinny, quiet high-schoolers when I first met them in 2008. Matt gravitated toward the service counter, while his younger brother shadowed his father in the pit house. Ricky hoped his second-oldest would succeed him as the head pitmaster at Scott’s-Parker’s but also feared what this would entail for the boy. “I want Zach to do this, but then again I think I’m going to deprive him out of his life. But he’s got to understand, you got to give up a lot to do this,” he told me, before listing the events that a dedicated pitmaster, in his estimation, must skip out on. “Vacations, going to ballgames and seeing your girl play softball or watching boys play football.” As Ricky wound down his list, it became quite clear to me that he was atoning, in his own way, for the moments and milestones that he had missed throughout his own life and the lives of his children. For Ricky Parker, barbecue came before all else: “If you got family that’s died, you can’t even go to a funeral because you got hogs cooking. There’s a lot of things you got to sacrifice.”

Ricky Parker would sacrifice them all.

COME JULY, 100 WHOLE HOGS

I last saw Ricky Parker on Thanksgiving Eve 2012. I was on the road, and, as always, hungry for a wholehog sandwich.

I peered in the back gate to the pit house. No Ricky. Walked through the front door and stepped to the ordering window. No Ricky. As I placed my order, a movement caused me to look over my shoulder. There sat Ricky Parker. I had walked right past him.

He was alone at a two-seat corner table, sitting down. This was a position I had seen him occupy only once before—four years earlier, when he finally succumbed to a seated interview. I have no doubt that he sat down to eat, at least on occasion. He obviously drove his truck while seated. A church pew, the dentist’s chair, his favorite La-Z-Boy recliner to watch Sunday-night football: he probably visited each once or twice since I’d known him. But I didn’t believe it; Ricky Parker was at rest.

From ten feet away I could tell that he was counting numbers, recording names, tallying orders. He was shuffling papers. This was another side to the pitmaster I had never seen, a side I immediately felt wrong bearing witness to: the ordinary business owner he was and had been for more than two decades.

I took a table next to the front door, facing Ricky so that I could watch him from afar. He appeared a pale shadow of himself: swollen face and puffy hands, skin gray, altogether sick. He looked as if he could hardly stand up straight, much less flip a hog, or twelve. The man who once bragged that he ran through five pairs of shoes annually looked like he hadn’t worn out a pair in more than a year. Staring at my order, which sat unwrapped on the table, I remained unable to force myself to tear open the wax paper. Just look at him, I thought; Ricky couldn’t have cooked this. I was panicked by what it would taste like. Would it still taste like Ricky’s barbecue? I could have painted a still life of that wax-paperwrapped sandwich in the time I took to unwrap my barbecue. I studied the paper’s creases and folds, the toothpick spear that held it all together, the grease smudges that began to soak through the paper to gradually and subtly reveal the sandwich within.

I carefully unpacked the sandwich and, tossing aside the top bun, warily gathered a strand of fatty, white-fleshed barbecue—it must have been middlin’—from the heap of meat before me. Before completely dispatching the first bite, I crammed a larger chunk into my mouth, then a third morsel. I swallowed the remainder of the barbecue in what felt like a single gulp, chewing without tasting, but knowing that if I could taste it, it would have tasted good. The same as it always was. Ricky Parker’s barbecue.

I stepped up to Ricky and said hello, as he, head down, continued to shuffle papers. Staying firmly planted in his chair, he shook my hand and, palming an unlit Swisher Sweet in his left, motioned for me to sit.

He had been counting turkeys, readying a stockpile of more than a hundred frozen, semisolidified, and defrosted birds for smoking on his barbecue pits to supply his customers’ holiday tables. Without going into the details or describing his health, he told me that he would be relying on his sons to barbecue this season’s turkeys and that he was thinking of taking some time off now that he could rely on Zach and Matt. We shared other news. He pulled from his wallet a photograph of his daughter, Hope, who had recently won Tennessee’s Teen Princess pageant, a sort of Miss America for juniors. I told him I hoped to write a book on whole-hog barbecue. He responded with a question—“Who else cooks hogs over wood?”—as if he were still the only one. I laughed and he winked. His eyes sparkled, prismatic and dazzling.

“July,” he told me, as I said goodbye. “Remember: July.” He reminded me of that magic number, the low race to one hundred smoked hogs.

But Ricky Parker would not live to see another Fourth of July. He would never smoke a pig on a New York City sidewalk. He would not fulfill his dream of cooking one hundred whole hogs.

Ricky was dying. For months Zach and Matt tried to get him to the hospital, but their dad wouldn’t go. He didn’t much believe in the expertise of doctors. And there was the business to consider: he would not leave his pit behind. Not yet. Though he hadn’t cooked many pigs over the last year—his sons had taken on most of his duties—Ricky stubbornly held on. He continued to cook only on Mondays, the slowest day of the week.

Years of suffering for his barbecue had taken its toll on Ricky Parker, but he would suffer on. “It was liver disease,” Matt told me later. “Liver disease that got up into his lungs, his kidneys. All but his heart. His heart was strong. He had a strong heart.” He still came to work every morning, arriving well before his sons, and sat near the door—right where I had seen him the previous November— conversing with customers and friends. He still couldn’t sleep, staying awake throughout those twilight hours, worrying over his hogs. He might now walk instead of run around the pit house, but his heart, that strong heart, would keep on running to the very end.

That heart finally gave out on April 27, 2013. Over thirty-five of his fifty-one years, Ricky Parker had smoked more hogs, burned more hickory, and worn out more pairs of shoes than any other pitmaster. His sons laid him to his eternal rest alongside his mother and father at the Natchez Trace Baptist Church Cemetery, choosing to bury him in his everyday uniform: blue work pants and a beige shirt with “Ricky” stitched across the left breast and a fivepack box of Swisher Sweets planted in the pocket. Whether or not there was barbecue in the afterlife, Ricky would take some smoke along with him.

After closing the business to bury their father, Zach and Matt would reopen Scott’s-Parker’s Barbecue one week later to little fanfare. The pits had never sat this quiet, this cold, for so long. But they would relight with ease. Barbecue, and whole-hog barbecue especially, has a tendency to endure, to survive the crushing stutters and stops of time and to linger in the imaginations of eaters. Ricky Parker might have been gone, but his sons still burned staves of hickory wood down to coals and fired their hogs every half hour for most of a day. The people of Lexington, Tennessee, still arrived hungry for whole hog, slaw, and hot sauce; the regulars feuded over the few orders of catfish and ribs; and the Parker boys often sold out of everything well before sundown.

I arrived two days prior to the first Fourth of July after Ricky’s passing. Not a chance I would miss this.

The date had become totemic, circled on my mental calendar for five years. This Independence Day, I long knew, fell on a Thursday, the start to the four-day weekend over which Ricky had wanted to cook one hundred whole hogs. I turned up just as Zach and Matt pulled into the parking lot with a pickup truck loaded heavy with freshly killed hogs. Zach had recently discovered weightlifting and the protein-rich lifestyle and could toss a pig around like a pillow. Matt was still skinny and quiet and looked even more like his dad than in years past.

The past ten weeks had been a series of ups and downs for Ricky’s young sons. Twenty-two-year-old Zach, operating under his father’s auspices, took the lead in running the barbecue place. Matt, nearly two years older, stuck by his brother’s side and, together with a small cluster of friends turned employees, ran the pit house, while crash-course learning the other side of any business—filing paperwork and paying the taxman. Of course there were doubters. People around town asked when the boys would install the gas lines to the pits, concluding that they would take the first available shortcut in crafting whole-hog barbecue. “A lotta family members and my girlfriend and friends, those that didn’t work here, asked if we would be able to keep it open,” Matt told me. “You know, being nosy.”

The past ten weeks had been a series of ups and downs for Ricky’s young sons. Twenty-two-year-old Zach, operating under his father’s auspices, took the lead in running the barbecue place. Matt, nearly two years older, stuck by his brother’s side and, together with a small cluster of friends turned employees, ran the pit house, while crash-course learning the other side of any business—filing paperwork and paying the taxman. Of course there were doubters. People around town asked when the boys would install the gas lines to the pits, concluding that they would take the first available shortcut in crafting whole-hog barbecue. “A lotta family members and my girlfriend and friends, those that didn’t work here, asked if we would be able to keep it open,” Matt told me. “You know, being nosy.”

As the brothers lifted the hogs from truck bed to walk-in cooler, they both looked to be operating at the razor’s edge of collapsing from exhaustion. “I haven’t had a day off since Dad passed,” Zach said.

And for that reason, the brothers had decided to forgo their father’s quest for one hundred hogs. Their July Fourth weekend would be spent on holiday, fishing and boating alongside their girlfriends and best pals. They would find time to drink to excess, barbecue something significantly smaller than a whole hog, and sleep in.

The brothers sold out of barbecue well before the Fourth had even dawned: 1,200 pounds, more than a half a ton of meat, spread among three hundred orders, from one-pound single servings to twenty-five-pound party trays, reserved weeks in advance. I woke early on the morning of the Fourth to witness the first order go out the door at eight a.m. and waited until the last departed seven hours later. I watched as customer after customer hugged the Parker boys and thanked them for continuing their father’s legacy. I saw many customers who had neglected to reserve their barbecue leave empty-handed and felt only half guilty when Zach handed me three pounds of white and dark, with my own squirt bottle of hot sauce on the side. I observed Zach and Matt hustle harder and faster than their dad ever had. And at day’s end, I watched as they shoveled sand into each of their barbecue pits, one by one, extinguishing the fires that once kept their father, Ricky Parker, awake at night.

Rien Fertel is a writer and teacher based in New Orleans, Louisiana. Denny Culbert is a photographer based in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Rien Fertel is a writer and teacher based in New Orleans, Louisiana. Denny Culbert is a photographer based in Lafayette, Louisiana.