TRUSTY TOOLS Champions of the Everyday

What do a well-worn glove and a sno-ball machine have in common? A good story, and in the case of Grady's Barbecue and Hansen's Sno-Bliz, a lot of fans. Objects shape our daily experience, and as folklorist Henry Glassie wrote, “like a story, an artifact is a text . . . and a vehicle for meaning.”

Chefs, pitmasters, cheesemakers, and farmers rely on the tools of their trade. These objects matter more than than you might expect. This week, we share two stories of restaurateurs who use beloved tools to deliver delicious.

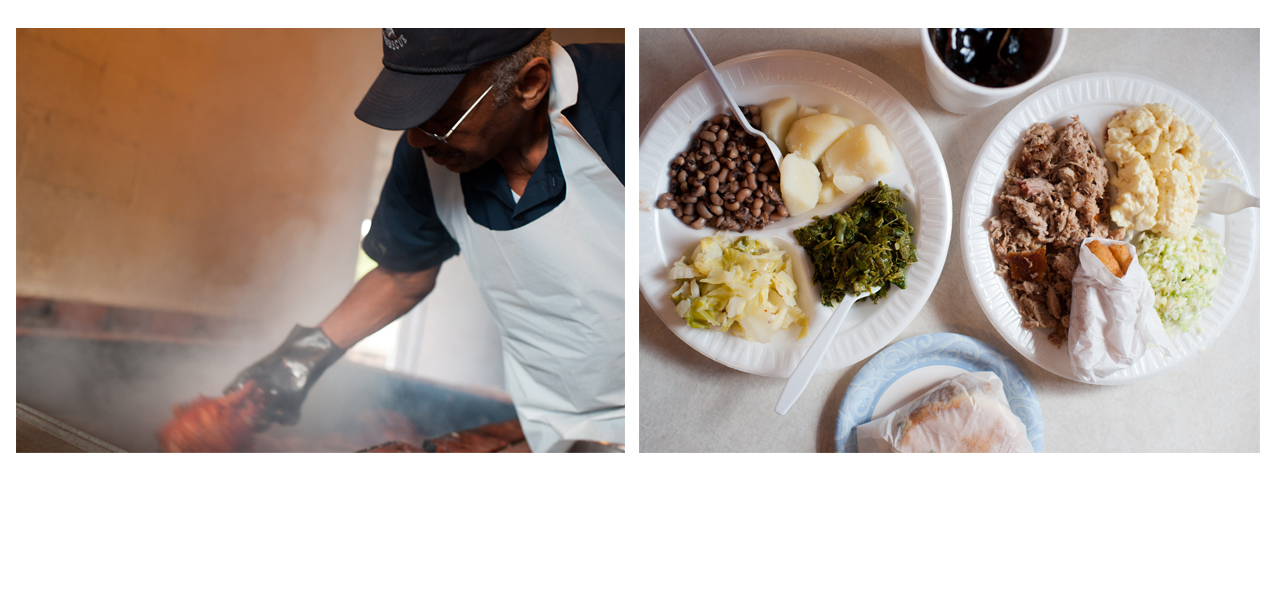

Stephen Grady and his wife Gerri own Grady’s Barbecue in Dudley, North Carolina, now celebrating its thirtieth anniversary. “Everybody seems to think their [barbecue] is better than the next person,” Stephen said in his 2011 SFA interview. “Some of it’s right and some of it’s not. But we think ours is the best.”

Stephen Grady and his wife Gerri own Grady’s Barbecue in Dudley, North Carolina, now celebrating its thirtieth anniversary. “Everybody seems to think their [barbecue] is better than the next person,” Stephen said in his 2011 SFA interview. “Some of it’s right and some of it’s not. But we think ours is the best.”

Before it was a restaurant, Grady’s was a corner store, then a gas station. To take over the business, Stephen left the farm and sawmill behind, and Gerri put her cooking skills to work, cooking boiled potatoes and black-eyed peas from scratch daily.

Gerri tells of how Grady’s came to be.

The verdict after 30 years in business.

Waller Matthew Grady, Stephen’s grandfather, taught him to tame and master a key tool, fire. “I have always known how to cook a pig,” says Stephen. “I can’t even remember when I learned how…And [our barbecue] is done the old-fashioned way, it’s basically the way my grandfather did.”

With heavy gloves and a shovel, Stephen burns his coals slowly. “You want to cook [the pig] at least six hours, and I think that’s the whole catch to it right there. You can cook it faster but you won’t get the same tastes.” Good barbecue means a wood-fired pit. Gas, Stephen explains, is not a tool he wants to use. “I don’t care how slow you cook it, there’s a difference,” he says. And it’s not a good difference.

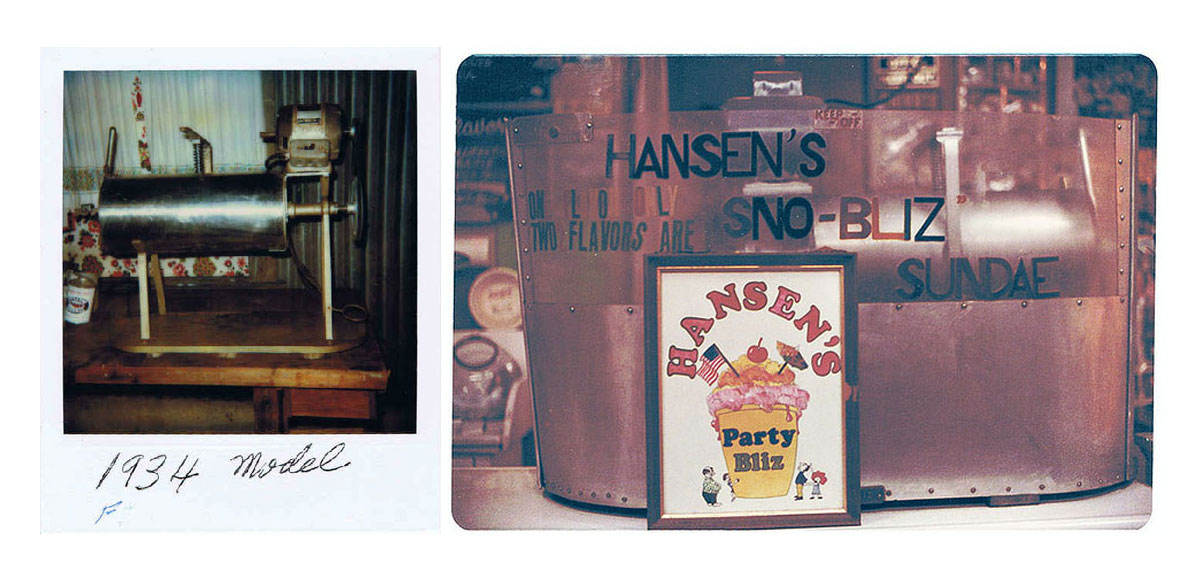

Pictures line the walls of Hansen’s Sno-Bliz. Since 1939, the Hansen family has cooled down New Orleans with their icy, fluffy, sweet, and sometimes creamy snow balls. Just as Stephen Grady learned to tame fire, Ernest Hansen learned to tame ice. “I wanted to make something for my children that is not touched by a hand,” he said of the original idea, which came to him in 1933. For the first couple of years, his “Snow Blizzard” or “Sno-Bliz” was a treat for family and friends. Before long, they moved their machine outdoors, snaked an electric cord through the front window, and sold Sno-Blizes for 2 cents under a tree in their front yard. Customers lined up for their delicious alternative to hand-shaved ice. In 1939, Ernest built his second ice machine and named it after his son, Gerry.

Pictures line the walls of Hansen’s Sno-Bliz. Since 1939, the Hansen family has cooled down New Orleans with their icy, fluffy, sweet, and sometimes creamy snow balls. Just as Stephen Grady learned to tame fire, Ernest Hansen learned to tame ice. “I wanted to make something for my children that is not touched by a hand,” he said of the original idea, which came to him in 1933. For the first couple of years, his “Snow Blizzard” or “Sno-Bliz” was a treat for family and friends. Before long, they moved their machine outdoors, snaked an electric cord through the front window, and sold Sno-Blizes for 2 cents under a tree in their front yard. Customers lined up for their delicious alternative to hand-shaved ice. In 1939, Ernest built his second ice machine and named it after his son, Gerry.

Ernest and Mary worked in their shop on Tchoupitoulas Street well into their 80s. In 1996 their granddaughter Ashley joined them. Mary made the syrups, storing flavors like spearmint, pineapple, coconut, and cream of nectar in her cousin Thelma’s old liquor bottles. The Hansens worked hard. Until Ashley came on the scene, Mary still fought shrimpers for the best 300-pound blocks of ice.

As Katrina bore down on New Orleans, Ashley disassembled her grandfather’s precious machine, ready to transport it to safety. Mary, who was had been ill, was airlifted from her hospital bed. Ernest evacuated to Alexandria, Louisiana. “They had never been separated before that,” Ashley’s father, Gerry Hansen explains. “He was panicking and wanted to know where she was.” Mary passed away two weeks after the storm. Ernest decided to live in Thibodaux, where she was buried. “He said, ‘I want to stay with Mary,’” remembers Gerry.

Mary ran a tight ship.

Crazy things happen at Hansen’s.

Earnest and Mary’s loving partnership and legacy live on. After the flood waters receded, Ashley and her father reassembled the Sno-Bliz machine. Hansen’s didn’t miss a summer. “We’ve lost so much in New Orleans, and we’ve lost a generation of people,” Ashley says in an SFA interview, “It’s just nice to be able to hold onto a few things that haven’t changed. We wanted to keep the sno-ball stand going at least this year for that reason.”

Next summer, Ashley will paint “Open 77 Years” on the side of her family’s stand. She still uses her grandfather’s machine, and mixes her syrups every day like her grandmother did.

Stephen Grady and Ashley Hansen now serve people by the hundreds, using the specialized tools of their trade. Tools with stories lurk in all kitchens. Worn, well-used, maybe a little grimy, our biscuit brakes and mayonnaise whisks, our crocks and can openers are totems of our labors, tokens of our families.

UP NEXT: We sidestep heritage to explore hard truths about the history of eating in the South.

This feature was produced with oral history interviews, audio, and photographs from the Southern Foodways Alliance. Historical Hansen’s Sno-Bliz photos are courtesy of their online exhibit and Flickr. Thanks to Landon Nordeman for allowing us to use his photographs. The quote in the introduction is from Henry Glassie’s Material Culture (Indiana University Press, 1999).