< Back to Oral History project: Tennessee Barbecue Project

< Back to Oral History project: Rural Tennessee BBQ Project

< Back to Oral History project: Memphis Tennessee BBQ Project

ORAL HISTORY

Whole Hog – A Slow-Smoked Story Cycle

Essay by Joe York

Everyday the South’s passion for the pig plays out in parts. Shoulders and skins, maws and middlins, ribs and lips, bacon and butts, brethren of one body split and spread about, each a denomination unto itself. But amidst this sea of pieces there are places unparted, where hogs are still wholly enjoyed. The Piedmont of North Carolina is one. The wrinkled carpet of western Tennessee is another. The latter is where we’re headed, up Highway 100 between Memphis and Nashville, to Jackson and Lexington and Henderson, into the Bermuda Triangle of barbecue.

We cross into Tennessee. Amy feeds her cameras. April looks over a list of questions, readying herself for the interviews she’s come to collect. I search the radio. War, static, weather, static, country music.

Chester County welcomes us. So does Henderson, the county seat, but we’re not stopping. We stay straight on Highway 100 toward Jack’s Creek.

A church sign on the side of the road ciphers salvation: 3 Nails + 1 Cross = 4 Given.

Two more miles pass. Creeks like gray hairs, hills subtle as shoulder blades in blouses, clear cuts here and there like the back of a bulldog a week after a fight, and then another sign of sacrifice.

Bobby’s Bar-B-Que. Beneath the name, as sober a pig as I’ve seen. This is how Baptists would paint barbecue signs if that’s what they did. Black and white, not a patch of pink on him, no cleaver hefting hooves, no silly chef’s hat, just a hog, the whole hog, and nothing but the hog.

So help me God.

Bobby’s Bar-B-Que, Jack’s Creek TN | Visit Bobby’s

Smoke is a funny thing. It takes clean things, like lungs, and makes them dirty while it takes dirty things, like hogs, and makes them clean. But the smoke that rises behind Bobby’s has another property. It hunts down the voluntarily meatless and reminds them of a time when their teeth had more to tear than the plastic wrapper protecting their tofu. The powers of the most verdant vegetarians are useless against it.

Consider my friend Sarah. When she walked into Bobby’s a few months ago and smelled that smoke, she was two years removed from meat. When she walked out, she had one hog sandwich in her belly and another in a bag.

But now April, who has come with me to collect interviews about the meat she won’t eat, is no lightweight. She’s in her seventh year. She sweats soy. As she leans against the cinder block structure that houses the pit readying her recorder, she doesn’t notice Ronnie working around her, doesn’t know he’s acting acolyte to her coming communion.

Beneath the blue cotton that covers him from cuff to collar, all of Ronnie’s muscles work against the log. His lips tighten, turning white against the brown and red of his brambly beard. His eyes, shadowed by the bill of a baseball cap with a lumber yard logo, guide the action.

He pulls back, as if angling against a gar, lifting the log. He charges the burner, a fifty-five gallon drum, dimpled and soot-stained, opened on one end into a mangled metal mouth that only eats newspaper and lumber yard leavings. [The area around the burner, where other burners cool and rust and wait, looks like what it would look like if a bunch of giants got together and went camping and drank giant cans of beer and then tossed them into their giant camp fire.]

Ronnie shoves the log deep into the drum and then gives it back to gravity. The fire rolls and settles, sending out a swarm of sparks like lawn mower pissed off yellow jackets.

April approaches and asks Ronnie if he’s ready to do the interview. “Just a second,’ he says reaching for the shovel, which he carefully loads with coals. As he walks to the pit the air moves over them. They glow and snap. April follows.

The shovel disappears into the pit. He twists the handle back and forth beneath the browning beasts, carpeting the floor with coals. April leans in to look and as she does a cloud of smoke escapes and wraps itself around her head.

Half an hour later, April sits inside the restaurant fidgeting. She doesn’t watch as I start to work on my second sandwich, just twiddles and stares at the table with the kind of worried wonder on her face that is usually reserved for ambulances or Ouija boards. And then, she stands and walks to the window. She hesitates, then lays two dollars on the counter and says it.

Bobby, that Bobby, takes the money and waits for Chad, the current owner, to assemble the sandwich. When Chad finishes, he hands the sandwich to Bobby who hands it across the counter to April.

She walks slowly to the table holding the sandwich out in front of her like a bomb or a dirty diaper. She sits down and unwraps the sandwich. She looks at it for a few seconds and then lifts it to her mouth. Her eyes close. Her cheeks take turns. The rise and fall of her Adam’s Apple.

I watch, waiting to see if she’ll change colors or explode.

Her eyes open. She looks down at the sandwich, which now resembles a meat-filled man- in-the-moon, and lifts it again.

C & R Grocery | Visit C&R

Driving by, C&R doesn’t look like much more than a good place to pee. Like any other small town gas and grocery it’s got a pair of unleaded pumps in front, a gravel lot next door for doling out diesel to the big rigs, and a banner out by the road marking it recent mustering into growing army of buffet pizza mongers.

But inside, sharing space with Snickers bars and Snapple jars, Hot Pockets and Pepsis,

and a variety of eggs ranging from Cadbury to quail, C&R has something most places don’t– whole hog sausage, killed and milled, sliced and spiced the same way on the same day of every week for more than twenty years.

And if we’d known that Tuesday was that day, we could have planned a little better, been there to see Bobby Connor, the owner of C&R, hacksawing his hogs, mixing muscle and fat, getting it all just so, until finally he’s able to finagle fourteen hundred pounds of pork into a tube.

Instead, we showed up on a Friday and Mr. Connor was away and the lady behind the counter kept looking at April who was walking around the store with the black case with the recorder in it. And April asked the lady questions about the sausage and Mr. Connor, and the lady answered stiffly and shortly, never taking her eyes off of the case, until, finally, she asked April what was in it, and April told her it was a recorder, and she said she thought it was a bomb and then said, “You never know these days.’

My Three Sons | Visit My Three Sons

Jimmy leads Amy and me into a room just off the kitchen. Utility lights attached to exposed trusses and studs cut diagonal shafts through the smoke. Jimmy approaches the pit and lifts one of the aluminum lids exposing a smoking hog. As he pats the pig on its browning butt he carries on a conversation with himself.

“Have you fired it, yet?”

“Nope, I haven’t fired it? Have you fired it?”

“I thought you fired it.”

“Well, if somebody fired it, it wasn’t me.”

And if he wasn’t intentionally twisting the phrase “fired it” into “farted,” we’d think he was nuts. Instead, we laugh and snort as he removes the loose cinder blocks from the side of the pit and inspects the bed of coals beneath the hogs.

He raises the old garage door and we follow him out to the burner. As he stokes the fire with four foot lengths of rough hewn hickory, rejects from a local ax handle factory, he grins goofily revealing his shiny, silver tooth. “Am I gonna be famous?” he asks Amy, who’s taking his picture.

He works the fire and I ask him about his life before barbecue. Filling a shovel with coals, he starts in on a story from his steakhouse days.

“I remember one time this lady came in and she would ask me for something and I would bring it and she would ask for something else and it went on like that for a while until I came back to the table and she looked at me and said, “Five minutes ago I asked you to bring me some coffee.’ And I said, “Ma’am, I remember you asking me for that coffee. I should’ve brought it and I didn’t and I’m sorry. No, I mean it, I’m sorry, no good. So what I’m gonna do is bend over right here and let you kick me in the butt just as hard as you can.” He stops for a second and flashes another sterling smile before continuing. “She tipped me five dollars after that.'”

By the time he gets to the bending over part he’s back at the pit shaking out a shovel full of coals under his hogs. When he’s done he leans the shovel against the pit and turns to me and Amy. “I’ve got a confession to make,” he says eyeballing his boots.

We wait, wondering what he’s got on his chest.

“I fired it.”

Bill’s Bar-B-Que | Visit Bill’s

When I turn my attention back to the table April and Bill are gone. I look up and see them disappearing into the back room.

I find them standing between two ping-pong table-sized stainless steel contraptions. A metal plate on the side of the one them reads “Hickory Creek Bar-B-Q Cooker,” but it looks better suited for pressing pants than cooking pigs.

“Where does the smoke come from,” April asks Bill who’s way ahead of her. “You see down here,” he says opening a little door like that of a post office box. Behind this tiny door lies a paperclip-shaped, electric element that glows a shade of red usually reserved for blast furnaces or the blinking eyes of radioactive movie monsters. “You just slide a stick of hickory in there every now and then and it makes plenty of smoke.”

He stands and lifts the lid of the electric pit. A cloud of smoke and steam rises and then disappears. We stare at the sweaty pig. As we watch it wading slowly into itself, a drop of fat works free, slides down the side of the pig and disappears only to reappear seconds later as the newest member of the meringue-like lump of lard that’s gathering in a galvanized washtub beneath the cooker.

Bill closes the cooker and takes us to the cooler where tomorrow’s hogs wait hoof-hung for their turn in the socket-fed fire of the cooker. We shiver and take turns slapping the hogs. Then we go to the kitchen.

On the walls above the chopping blocks and cleavers and volcano crock pots full of baked beans, are a number of drawings made by Bill’s granddaughter. Most of the drawings belong to “butcher paper pigs with styrofoam plates for heads’ genre. But one piece breaks sharply in form from the others, standing on its own as the beginning of a pork-based, Crayola-conceived calculus. A crude copy of the equation follows:

AMY: what I would like here is a picture, drawing, something that you have or that you could do that will illustrate the funny equation – something like Sandwich + person ‘ Hog – I can’t remember exactly – If it’s not possible, let me know so I can reword things a bit.

Papa Kay Joe’s | Visit Papa Kay Joe’s

As we travel east on 100 Tennessee breathes, expanding slowly, then falling, then building again. The land of whole hog barbecue is behind us for now, smoking somewhere beneath the sauce-red sun I see sinking in my rearview mirror. Up ahead at Papa Kay Joe’s, a little shy of Centerville, a sandwich awaits. But, considering its components, “sandwich’ seems a poor word for what it is. A cornbread bun lacquered with lard vowing to have and to hold a pile of barbecued butt, it’s more of a marriage. And behind this marriage is another.

Married right out of high school, Devin and Angie Pickard have been together for more than half of their lives, and for the last three years since opening Papa Kay Joe’s they’ve been absolutely inseparable. They share the work, but as far as the sandwiches are concerned she makes the hoe cakes and he smokes the butts. And when their talents meet, it’s enough to make you drive a hundred miles out of you way, which is exactly what we’re doing. And as we drive on I think about the first time I met the Pickard’s and saw their sandwich in action.

It was the Fall of 2002 in Oxford, Mississippi, at the 6th Annual Southern Foodways Symposium. This installment of the symposium was touted as a three day barbecue free-for- all, and as part of the festivities the Pickard’s had been invited to compete in a suppertime showdown called “Battling Barbecue Sandwiches.’

The original fight card had the Pickard’s, relative unknowns, going head to head with J.C. Hardaway, one of Memphis’ oldest and finest barbecue pit masters. But, the day before the battle, Mr. Hardaway fell ill and John Currence stepped into his enormous shoes. With a list of culinary achievements as long as his leg and a restaurant with more stars than most generals, Currence is nothing less than the Iron Chef of Oxford. But accolades aside, he had only one day to assemble an arsenal, so he and his crew worked through the night preparing fried pork chop sandwiches.

High noon the next day found Currence scrambling madly about establishing his lines. As he dug in, the Pickard’s approached calmly carrying trays heaping with hoe cakes.

The crowd, which had been growing steadily in anticipation of the duel, stared as the Pickard’s passed. Some ooohed. Others ahhed. One woman, obviously overdressed, wondered aloud, “What are we supposed to do with those?’ Currence knew. He stood, squinty-eyed in the sun, nodding in admiration of the Pickards’ tactics.

With everything in place the battle began. Currence passed out the pork chop sandwiches. The Pickards piled pork onto the hoe cakes, sauced it liberally, and slid the sandwiches onto waiting plates. As the people ate they murmured through their cud calling Currence’s creation inspired while simultaneously hailing the Pickard’s hoe cake sandwiches a meteoric hit. As the deliberations drew on Currence received the respect he deserved, but “Pickard’ was the name rolling off of the crowd’s giant tongue.

Strangers with strange buns, they had marched into Oxford and won praise on par with the town’s most celebrated chef. And they didn’t gloat either. They just went right on trading cakes for compliments and as they did the finger lakes of accidental grease that covered their smiling faces shimmered in the October sun.

We pull into the parking lot. And as we walk into their restaurant, Devin looks up from his meat and Angie from her cakes and they say hello and we say hello and then Devin asks how everything is in Oxford. I lie and say “Fine. Everything’s fine,’ when what I should’ve said is, “Different. Everything’s different since y’all left.’

B.E. Scott’s | Visit Scott’s

A sign made of what looks like a piece of an old counter top hangs by two twisted grey cables from the inside handle of the glass door. Its black, magic marker message says SOLD OUT. And despite the sign and the fact that I’m standing in an empty parking lot under a smokeless sky I can’t believe that at fifteen til noon on a sunny Saturday Scott’s has already sold out of sandwiches and sides and decided to call it a day.

Walking around the restaurant the only signs of life are the names of Joy and Nick, whoever they are, fingered in the dust that covers the dining room window. I am starting to think that SOLD OUT is an understatement, that they ran out of everything and split town, but then a lady comes out of the restaurant to see about us.

Amy, the photographer, asks her if she owns the place. “No,’ she says, “I just work here. Ricky’s the owner. He’s gone up to the armory, but he’ll be back soon if y’all want to wait.”

We give up on him and are about to leave when a big, black truck followed by a big, white cloud comes plowing through the gravel parking lot. A man gets out of the truck and hurries into the restaurant. Through the glass we can see him moving manically within. His blue pants are a blur, his t-shirt a trailer in a tornado, the bill of his baseball cap an oscillating floor fan gone haywire.

He comes back out with a stack of aluminum trays and heads for the bed of the truck. Hearing us approaching through the gravel he turns to face us and for the shortest of moments stands absolutely still.

“Are you Mr. Parker,’ April asks.

“Yes, but””

Before he can finish April opens fire, telling him that we are with the such and such and that we’re doing a so and so about barbecue and we would really like to interview him and if he just had a few minutes it wouldn’t take long. Amy follows suit asking if he minds if she takes some pictures of him.

His legs twitch, his fingers wiggle like worms in his pockets, and when the silence finally comes he fills it with apologies. And it’s not that he doesn’t want to help. It’s just that he’s got seven hundred and fifty people to feed tonight at the armory and he’s been up all night with the hogs, and he’s got to get these trays across town, and then there are the sides, and…

He goes back inside and for the second time we turn to leave. As we pile into the car he comes out and gets in his truck and starts to take off and then he stops and leans out the window and yells to April, “Hey! If you want to ride with me over to the armory we can talk in the truck.’

As Amy and I wait in the car for them to get back the lunch crowd comes in. Minivans and sedans, trucks and Trans Am’s, all American made, roll into the lot, see the SOLD OUT sign, and roll back onto 412 turning towards the Wal Mart and the remora-like row of fast food restaurants.

A truck with a bass boat in tow pulls in and stops. Three middle age men wearing NASCAR hats with the numbers 8, 3, and 43, respectively from left to right, approach the door. “They’re sold out,” says 3 to 8 and 43. 43 repeats the phrase in disbelief, “Sold out?” 8, unshaken, suggests Hays’. 3 and 43 agree and they climb back into the truck and pull away.

Hays Smoke House | Visit Hays

As we sit in the car gathering ourselves for another plate of pork, the fifth in less than twenty four hours, a Cadillac pulls into the space beside us. Two geriatric gentlemen and their wives climb out, creaking in concert with the closing car doors. We walk behind them to the restaurant, intentionally stifling our steps. When we get there, the fatter of the two men, who had been driving, holds the door open for us. We reach the counter and wait for the fragile foursome to order, ignorant of the fact that we have already begun a backwards, barbecue-based tour of the making of America.

With the old people out of the way, we order and take a seat. Around us hoes and harnesses, scales and scythes, wash tubs and triangles hang from rusty nails driven into the unvarnished, cedar-skinned walls. Tools turned antiques, these old implements are no longer symbols of work to be done. Instead, they stand as the collected kitsch of a nation already assembled.

Mr. Hays comes over to our table and asks if we’re enjoying the sandwiches. We trade small talk. Then he checks his watch and says, “I’ve got to go see about my hogs. Y’all want to come back with me?”

He leads us through the kitchen and out the back door to a tin roofed, open-sided structure. A black cylinder, bigger than a bus, claims the lion’s share of the space under the exaggerated shed. “Is that an old underground gas tank,” I ask Mr. Hays. “Sure is,” he says. “A few years back all the gas stations in Tennessee had to dig “em up and put in new ones. This one had only been in the ground for two years when I got it.” Upon its resurrection, Mr. Hays took it and turned it into one of the most ingenious pig cookers the world has ever seen.

As he explains the electric damper system he installed to ensure that the hickory coals neither flame nor fizzle, he lifts one of the three doors cut into the side of the cylinder. Round and round go the pigs, riding the rotisserie, unwilling passengers on this Ferris wheel of smoke and fire. If Dante had designed a circle of hell for hogs, this would be it. But it’s more. It is an emerging nation, where newly imagined machines take time consuming traditions and make them manageable enough to market. But there is another world feeding the first two, a world in which Mr. Hays spends most of his days.

As he slides his hand into a green, rubber glove, preparing to pull pork from a finished hog, he explains that the we won’t be going to the slaughterhouse. It’s only open Monday through Thursday, the days that he’s too busy killing to cook. I ask him how he does it and he tells me he prefers shooting to stunning. “Sometimes when you stun “em they have a habit of coming to at the worst times,” he deadpans. And as his fingers ply the pig for pork, all I know is that somewhere down the road this slaughterhouse stands, with its hog shooting, blood letting, gut wrenching work as the first step in the pig’s inevitable progression from the bullet to the bun, a frontier where men and the nature that nurtures them still struggle.

We thank Mr. Hays and leave. Walking to the car I see the front of the Cadillac for the first time. Under the gleaming grill screwed to the front bumper is a vanity tag that reads, “Forget 911. I dial .357.” Beside the statement a disembodied hand points a hognose six shooter at my shins. And in that instant I imagine that fat, old man, who smiled and held the door for us, standing in a Stucky’s somewhere and seeing that tag and leaning down and taking it into his own hands and smiling because he had finally found the one thing that adequately articulates his lust for lawlessness, and I wonder which America we’ve walked out into.

Foster’s Bar-B-Q | Visit Foster’s

About a week after we got back from our barbecue tour of western Tennessee, I attended a fiction reading at the University of Mississippi where I am a student. As I waited with the others for the writer to arrive I listened to the little conversations going on around me. Of the thirty odd voices contributing to the growing murmur one stuck ou. And this voice, this New York taxi cab of a tongue, with it’s hard g’s and t’s and complete lack of elision, came from a woman sitting across from me who was using it to test her northern notions of her southern surroundings.

“It’s not as hot as I thought it was going to be,” she said the old man in front of her. “What’s that?,” he answered, realizing a little late she was talking to him.

“I thought it was going to be hotter than it is down here” she repeats.

And as the man considered the temperature, I realized that this was the beginning of the old “Tell me about the South” interrogation that northern travelers sometimes use to see if the South really can be boiled down to grits.

“Me, too,” he said finally answering her kind-of question with a half-smile. And with weather out of the way she moved on to food, asking the man where she could get a good southern meal. As he rattled off a list of places from gourmet restaurants to gas stations, I thought about chiming in and telling her to drive up to Tennessee and go to Foster’s Bar-B-Q. And what kept me from speaking was that I didn’t want her, this wanker of a Yankee, to know where it was. And even if I’d told her about it, I don’t think she would’ve gone, but I should have at least given her the option of going to the one place that could simultaneously confirm the cliche of the South she thought she knew and provide the antidote for her advanced case of amateur anthropology.

Occasionally, though, I like to think that I told her and she took my advice and headed up to Tennessee, traveling east of Henderson on 100 until she got to 22. And there in the southeastern quadrant of that crossroads she would see the aluminum shack and the sawhorse-supported sign out front that says simply “Bar B Q Today.’ And she would park her rental car in front of the painting on the side of the building with the pig waitress who’s carrying a pig sandwich as big as her big, pig head. And above this, hanging from a telephone pole, she’d see the Confederate flag furling and unfurling in the smoky breeze and she’d have no reason to believe anything she didn’t already.

But then she’d go inside and step up to the counter and Wilma, who runs the place, would emerge from the back room. And Wilma would tell her that she was back at the pit flipping the pigs and that’s why it took her so long getting to the counter. And Great Northern [we’ll call her Great Northern] would stare at Wilma and say, “I’m sorry, but did you say thaT you were flipping the hogs?” And Wilma would reply, “Yeah, you gotta flip “em over for the last couple’ov hours to keep “em from burnin’ up.’ And Great Northern would sit her Kate Spade handbag on the counter and look up at Wilma and say “You mean to say thaT you have hogs back there?” And Wilma would say, “Last time I checked. You wanna see “em?” And they’d go back to the pit and Wilma would raise the lid exposing a freshly flipped hog and then look at Great Northern and ask her if she wanted some and Great Northern would just look at her and then at the hog and then back at her. And Wilma would reach down and pull a stringy wad of pork from the pig and hand it to her. And Great Northern would take it and look down at it and then back at Wilma, who’s giving her a look as if to say “Go on,’ and then she’d stick it in her mouth. And in that instant of hilarious, gothic goodness Great Northern would be able to stop asking questions of the South and just accept what it gives her.

But I don’t think it would’ve happened like that.

Artrageous Cookers | Visit the Cookers

We didn’t mean to go to Art’s. We didn’t even know it existed, and even if we did know about it we wouldn’t have thought to go there, seeing as it’s a bar not a barbecue restaurant. But strange things happen inside the Bermuda Triangle of Barbecue. It is as if this area of western Tennessee between Jackson, Henderson and Lexington, functions according to its own, miniature version of the chaos theory, one with more dire and immediate concerns and consequences than some butterfly flapping its wings in the Philippines and setting in motion a series of events that culminate with a tornado in Texas. And these concerns and consequences will be different for you than they were for us and this is because the Triangle works a new plot for every visitor and every visit. As for us, our concern on this trip was a flat tire and our consequence was Art’s.

The tire had been a problem since Bobby’s Bar-B-Q, the first stop of the tour. As we sat inside eating our sandwiches a woman who had just picked up her order and left came back through the door and announced that whoever had the car with the Alabama tag had a flat tire.

I felt around the flattening radial until my fingers found a postage stamp-sized piece of metal embedded in the tread. After repeatedly filling and refilling the tire with air and being told by three different repair men that the gash in the rubber was irreparable, I put on the spare.

The next day found us lost somewhere in Jackson. We pulled into an Exxon to ask for directions and as the attendants, Billy and Derrick, explained the way to my traveling companions, I noticed that they dabbled in tires. Within five minutes, Billy had removed the metal from the tire and Derrick had replaced it with a rubber plug about the size and shape of a tarantula. I told them what the other tire repairmen had told us and Derrick said stoically, “Everyday we do something everybody said can’t be done.”

And with that we drove away and immediately got lost again and that’s when Amy saw it. From the passenger seat she exclaimed, “Oh My God! Stop! Look at that! Stop!” Then I saw it. “Holy s*@#,” I said unable to help myself. “Is that a dumspter? That’s a &%$@#%$ dumpster! Don’t tell me they’re cooking barbecue in a $%# %@*# dumpster!”

And this was no regular dumpster. Besides the fact that it was smaller than a normal dumpster, it was outfitted with two small smokestacks, a built in thermometer, four adjustable dampers, an interior rack to hold the meat above the coals, and two little doors cut into the bottom of either side through which the coals were fed. On the back of it someone had painted a pig wearing a tuxedo next to which were the words “Artrageous Cookers.” And as if the dumpster turned barbecue pit wasn’t enough, it was bolted to its own little trailer. And the trailer, with its retractable benches and steps, was as masterfully engineered as the dumpster.

Billy, one of three men tending the dumpster, who bears a striking resemblance to the lead singer of the group Alabama, took two steps toward us in his ostrich skin boots and said, “I bet y’all never seen anything like that before.”

“Nope,” I said. “Never.”

Billy continued, “You know Art, the guy that owns this place, keeps saying he’s going to paint some flies and some rotten carrots on the side of it.”

As we laughed, Haley, one of the other two men standing around the smoking dumspter, chimed in, “Hey, how’d y’all find out about us anyway?”

Joyner’s Bar-B-Que | Visit Joyner’s

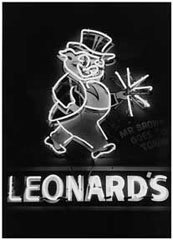

In every barbecue restaurant I’ve ever entered there is always one thing besides the food that stands out. At the Dreamland in Birmingham, Alabama, it’s the neon sign above the pit that says “NO FARTING.” At The “49er in Loxley, Alabama, a little rib place run by a Native American, it’s the sign behind the counter that reads, “Andrew Jackson: America’s Hitler.” At Corky’s in Memphis it’s the cloth napkins.

And for a while I thought the paper towel dispensers at Joyner’s would be the one thing I would always remember. And these dispensers are on every table and they look like pigs and their tails function as the axis around which the paper towels spin. And looking at them I was reminded of the bull’s head that Picasso once made out of a set of handle bars and a bicycle seat. And in that instant I formulated a theory. And this theory incorporated Picasso’s bicycle bull head and the Joyner’s paper towel dispensers as two instances where basic pieces of the material culture had been reworked to represent those things which have the greatest hold on a region’s collective imagination. So that in Picasso’s Spain, the mind subconsciously tended toward the bull, and in the Joyner’s South, the pig. And with that I thought I had really hit on something, but when I asked Patty, who runs the place with her husband Joe, if she made them or had them made, she told me that they came from a catalogue. And so with a gaping hole in my theory and a biting reminder that thinking too much is a bad thing, I starting looking for something else.

And that’s when I saw the picture of the bride on the baker’s rack.

“Is it possible that I saw this same picture at Bill’s?,” I asked Patty.

“Which one?,” she asked looking up from a griddle full of fried pies she had just started to browning.

“The bride.”

“Oh, that’s my daughter. Yeah, Mom and Dad have one in their place, too.”

“So Bill’s”

“My father.”

“Huh. Well, your dad’s a real nice man. He gave us some of those same kind of pies.”

“Well, they’re not exactly the same. I brown mine a little and he just leaves “em like they are. We’ve got a little bit of a competition going when it comes to the pies. What’d you think of his?”

And the look on her face when she asked me what I thought of her father’s pies was the thing I’d been waiting for. It was the same look my mom gives my grandfather every June when he announces that he already has ripe tomatoes in his garden. It was the silent, louder version of “Is that right?”

Then she slipped the spatula under a fresh, hot, golden, brown, shimmery, friendly looking pie and pointed it at me. “Here try this one and see what you think.”

Sam’s Bar-B-Q | Visit Sam’s

Leaving Joyner’s we travel outside the Triangle heading north to Humbolt in search of Sam’s. Located about fifteen miles north of Jackson, Humbolt is a place that reminds people from other towns, where bakeries have become boutiques and banks have become book stores, of a world before Wal Mart. Here, stores are still stores. The hardware store still sells hardware. The movie theater still shows movies. And on the outskirts of this town that doesn’t seem big enough for outskirts we see a sign that says “Sam’s Bar-B-Q.” And painted below the name is a man wearing a hat that says “Sam’ and he’s running for his life from the pig who’s chasing him and swinging a gleaming cleaver.

Just inside the door a man sits cross-legged reading the front page of The Jackson Sun. “Are you Sam,” my traveling companion April asks. He neatly folds the paper and sets it in his lap. “Yes ma’am, I’m Sam,” he says. “And that’s my wife Mary over there,” he continues, pointing at the woman behind the counter.

As April talks to Sam and Mary, a man drives up in a Toyota truck and comes in to get a sandwich. Mary takes his order and disappeares behind a plastic curtain. She returns with the sandwich, which the man pays cash for, and then sits down across from me at the only table in the tiny place. And as Sam talks to April about his barbecue, I watch the fruits of his labor in action.

The man, a shortish, fattish, mustached man, who was old enough for hair to be growing out of places it shouldn’t, unwraps the sandwich. His first bite is the biggest, taking out at least a fourth of the sandwich. As he chews and smacks and closes his eyes, I think he might disintegrate into the joy, but then he just swallows and lifts the sandwich again. The second bite is smaller than the first. Watching him chew it I have the feeling that he is trying to pace himself, like a marathon runner who starts too fast and then realizes what’s ahead of him. By the fourth and fifth bites he is obviously in pain, a very, very good kind of pain. And I say this because while he had once enjoyed some distance from the table, his face is almost on it now. It is as if some invisible hand on the back of his head is pushing it down and he is pushing back against it with just enough strength to keep his face out of the sandwich.

When he’s done, he turns his attention to the can of Coke. He cracks it and lifts it high, stopping only once to catch his breath, which by now was shallow and labored. He sets the Coke down, stifles a burp, and then does something extraordinary. He stands and orders another sandwich and another Coke to go.

And as he waits for Mary to return from behind the plastic curtain with his second sandwich, Sam and April walk out the front door. I follow and find them looking up at the sign. “My son painted that sign,” Sam says. “And I like it, but I don’t know why he had to make me so ugly.” Right then the man walks out into our laughter with his sandwich in one hand, his Coke in the other. He says a word of thanks to Sam, gets in his truck, and drives away. “God, I hope he doesn’t try to eat that while he’s driving,” I think to myself as I watch his truck disappear down the road.

April and Sam are still talking. Then Mary comes out the front door. “We’s just talking about the sign,” Sam says, catching her up on the conversation. “Oh, our son painted that sign,” she says looking up at the cartoon hog chasing her cartoon husband with a cleaver. And then she looks at Sam and says, “I still don’t know why he had to make you so ugly.”

Helen’s Bar-B-Q | Visit Helen’s

We left Sam and Mary standing in the parking lot beneath the sign and headed southwest on US Highway 79. And a few miles shy of the Brownsville town square we pulled into the parking lot in front of Helen’s Bar-B-Q, the last stop on our barbecue tour of rural western Tennessee. To this point we had visited ten other restaurants. And of these restaurants some came close to being shacks and others came even closer to being Cracker Barrels, but nothing we had seen prepared us for Helen’s, which, for all intents and purposes, is a barn.

And though Helen’s looks for all the world like a barn, it is not the farm kind of barn. It’s more of a downtrodden Dairy Queen. And that’s not to say that it’s falling apart, because it’s not. It’s just to say that the fact that it’s open and doing enough business to fill the parking lot with cars, says that whatever’s going on inside is a hell of lot more important than what’s going on outside.

And inside, Helen Turner, who for fourteen years served somebody else’s shoulders, puts her experience to work for her own pocket. From lighting the hickory to handing the smoked shoulder sandwiches to waiting customers, she does it all.

When we found her she was chopping up a shoulder to fill a take-out order. And as Helen skillfully carved away the excess fat from the shoulder April watched with an almost insane interest. In case you don’t remember, April, the oral historian, the interviewer, joined this tour as a vegetarian seven years removed from meat. But in the three days that we spent in western Tennessee, she ate five barbecue sandwiches and half a chicken.

And in the time between our first and second trips to Tennessee she told her husband about her behavior. And he wasn’t mad so much as jealous. An avid meat eater, who has lived with her for the better part of her affliction, he has become a vegetarian by proxy. And so, when he found out that she had not only eaten meat, but she had eaten it without him, he demanded a take-out order from the last stop on our tour.

And so, when Helen finished filling the order that she was working on, April placed one of her own. And at first, having vowed to return to the wagon, she only ordered enough for her husband. But as Helen resumed the cutting and the chopping and as the smell of the smoke escaped from deep within the shoulder, she succumbed. “Um, Helen,” she said barely louder than a whisper. “Yeah,” Helen said, never looking up from the shoulder. “You’d better make that a pound,” April said, still speaking sheepishly. “You say you want a pound,” Helen said seeking confirmation. “Yes. Yes, I would like a pound,” April said in an authoritative voice I’d never heard from her. “And some extra sauce.”

—

And so it goes in the Bermuda Triangle of Barbecue. Hogs spin and smoke in gas tanks, cornbread acts like hamburger buns, hats talk to each other, flat tires lead to barbecue a la dumspter, fried pies struggle for supremacy, men run scared from cleaver swinging hogs, and vegetarians are reminded why God gave them incisors. And aside from all of these odd happenings, the Bermuda Triangle of Barbecue in western Tennessee is a little different from its Atlantic namesake in that it doesn’t keep you from leaving so much as it makes it so you won’t want to.