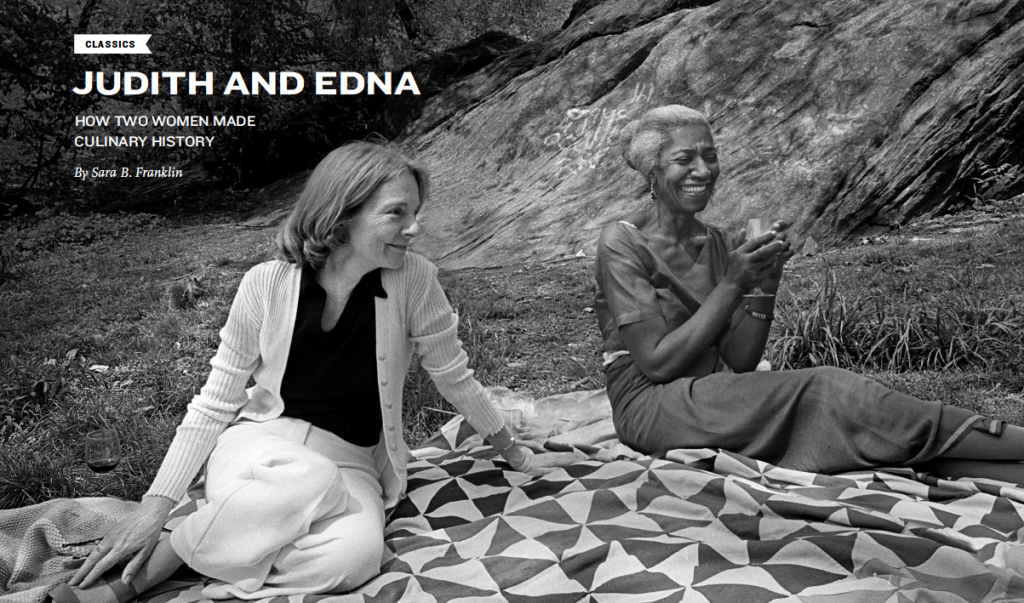

Here’s a tidbit from the latest issue of our Gravy quarterly. The author of this piece, Sara B. Franklin, is a doctoral candidate in food studies at New York University. She is currently working on an oral history project with editor Judith Jones, exploring food and memory.

Today, “local” is such a culinary buzzword that it’s almost passé. Good chefs interpret the places from which they hail, and nowhere has this revival of place been stronger than in the American South. In a cultural moment like this, we forget it wasn’t long ago that much of America was ignorant, if not downright ashamed, of its regional cuisines. Judith Jones, a longtime editor at Knopf in New York City, who retired last year at age eighty-eight, helped introduce American palates to international cuisines and elevate domestic regional foodways. Her interest in regional cookery was piqued by Edna Lewis, the Virginia-born chef and writer.

Jones was still a wet-behind-the-ears junior editor at Knopf when she shepherded Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking through publication in 1961. At the time, postwar prosperity brought boxed cake mixes and frozen vegetables to supermarkets, promising quick and easy paths to domestic bliss. Child and Jones weren’t fooled. Really good food, they knew, demanded an attentive and skillful cook, one who wasn’t afraid of having a bit of fun.

Over the next decade, Jones edited writers who helped usher international techniques and ingredients into American home kitchens. Marcella Hazan gave us brilliant minestrone. Irene Kuo taught us to listen for the sound of a properly heated wok. Claudia Roden introduced us to Middle Eastern mezze. And Madhur Jaffrey taught us to prepare an honest curry.

***

Judith Jones was an accomplished and prolific editor of fiction. Among others, she edited John Updike and Anne Tyler, two accomplished explorers of the nooks and crannies of American cultural landscapes. Her interest in workaday lives, and in the factors shaping American culture in the second half of the twentieth century, eventually drove Jones toward American food.

On a trip to Georgia in the early 1970s with her journalist husband, Evan Jones, who was researching his 1975 book, American Food: The Gastronomic Story, Jones noted a lack of “good Southern cooking” in Atlanta. To get their fix, they sought out rural boarding houses where they ate fluffy biscuits and perfectly fried chicken. American regional cooking, she recognized, was fast disappearing. Jones thought she could do for American food what she had done for French. She believed she could get recipes and stories on the page and encourage home cooks to keep the pots of tradition simmering. She began that quest by collaborating with Edna Lewis.

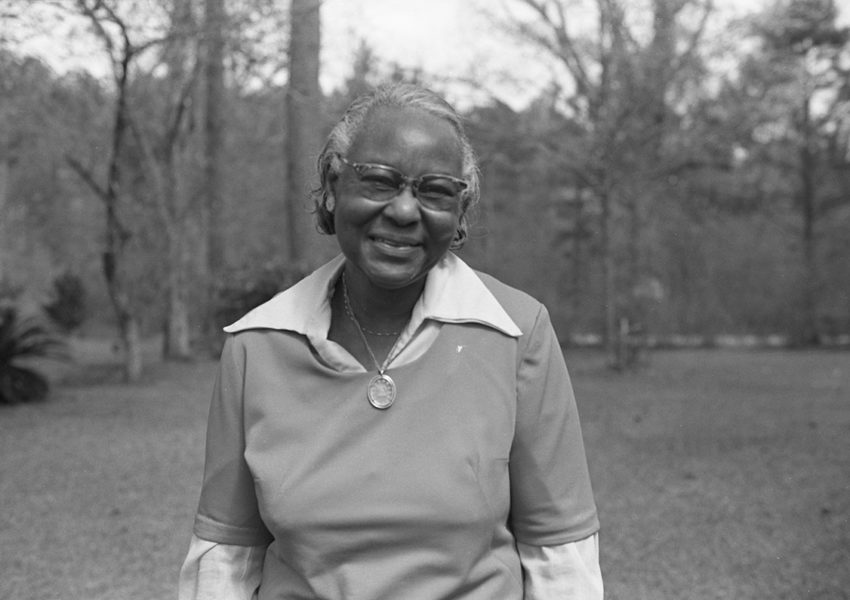

Jones narrates her life as a string of lucky breaks. Her story about meeting Lewis is no different. A native of Freetown, Virginia, Lewis had earned a cult following while cooking a mix of Southern and French cuisine at Café Nicholson on New York’s East Side. Lewis wanted to write a cookbook, and an agent had set her up with a collaborator. After a few months of false starts, the chef and her writer were sent to meet with Jones, who was known by then for her skill at coaxing prose out of novice authors. Jones remembers, “It was when she started to talk. All I did was ask some questions! You knew how much she knew when she started telling the story about her mother, who used eggshells to put seeds in so they could go into the ground on the first warm day.”

Soon stories of Lewis’s upbringing burbled up. Jones dismissed the collaborator, and she and Lewis began to meet regularly in the Knopf offices. While Lewis talked, Jones scribbled notes. At the end of their first session, Jones knew they had struck gold. “Write it just as you remember saying it,” she told Lewis. And so it went. For months, the two tugged together at the threads of memory and massaged them into what we now know as Lewis’s signature voice—certain, evocative, and no-nonsense.

Knopf published The Taste of Country Cooking in 1976. It was filled with recipes and stories specific to Lewis’s home, from biscuits and busy day cake to menus for hog-killing and Emancipation day. All focused on the ingredients and traditions of place. And not just any place, but the American South, the region so long dismissed by the food cognoscenti. Lewis gave voice to African American communities while highlighting the beauty that illuminated the long shadow of slavery.

As it happened so many times in Jones’s career, relationships that began in the office turned personal. Jones chose her authors carefully, and most became dinner-party guests, visitors to her country home in Vermont, and mentors, both in and outside of the kitchen.

In the early 1980s, Jones was wrapping up a book on hunting and fishing with Angus Cameron, a fellow Knopf editor. “Edna knew that I was working with Angus, so she had some ideas,” Jones recalled. “She said, ‘I wish I could get you squirrel. Because we used to get them right in Central Park.’” Her brother George Lewis still hunted them in the Virginia woods. Laughing, Jones recalls, “So she got her brother to send these little dead squirrels by Fed-Ex. I mean, they’d been shot the day before. So I skinned and prepared them, and I made squirrel stew. And it was just delicious!”

Their friendship was intimate, and Jones’s memory of Lewis is reverential. “I was so genuinely taken with her that it must have reached her,” she recalled. “Edna taught me a lot about what I care about, human nature.” Jones remembers Lewis as among the gentlest and humblest people she ever knew—sure, but never showy.

After publishing Lewis’s first book with Knopf, Jones signed more authors to tell the culinary story of America. She published books about New England cooks and the Northern Heartlands. But the South had caught Jones’s eye. For her visionary but underappreciated Knopf Cooks American series, Jones commissioned Barbecued Ribs and Other Great Feeds (1987) and The Florida Cookbook: From Gulf Coast Gumbo to Key Lime Pie (1993) from writer and editor Jeanne Voltz, a native of Florida. Preserving Today (1992) was written by Jeanne Lesem, who grew up in Depression-era Arkansas eating her mother’s pickles and preserves. Perhaps most famously, she published Biscuits, Spoonbread & Sweet Potato Pie (1990) by Southern food evangelist Bill Neal, the chef-owner of Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Jones’s late career didn’t ignore the world outside American borders. But more each year, she explored international cuisines to better understand what was happening here at home. As Americans learned more about the world through travel, and as more immigrants came ashore, we recognized the distinctiveness of our own culinary cultures.

Jones’s work with Edna Lewis and other Southerners helped lay the foundation for today’s resurgence of regional food. Think Sean Brock and Vivian Howard, both of whom are now at work on their own place-based books. Over a fifty-year career, Jones helped us narrate and make sense of our young nation’s complex history. Her ideal was not a melting pot, but a patchwork quilt, the better to honor what each region and individual has brought to the great American table.