THE BIG TOMATO Bedford, Virginia’s unlikely art scene

by Emily Wallace (Gravy, Summer 2016)

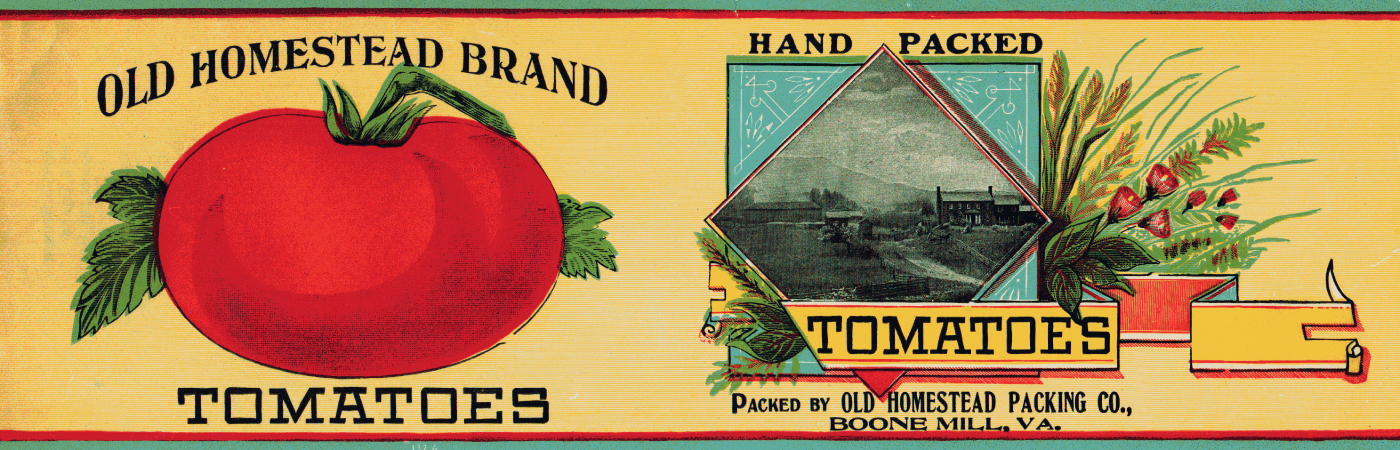

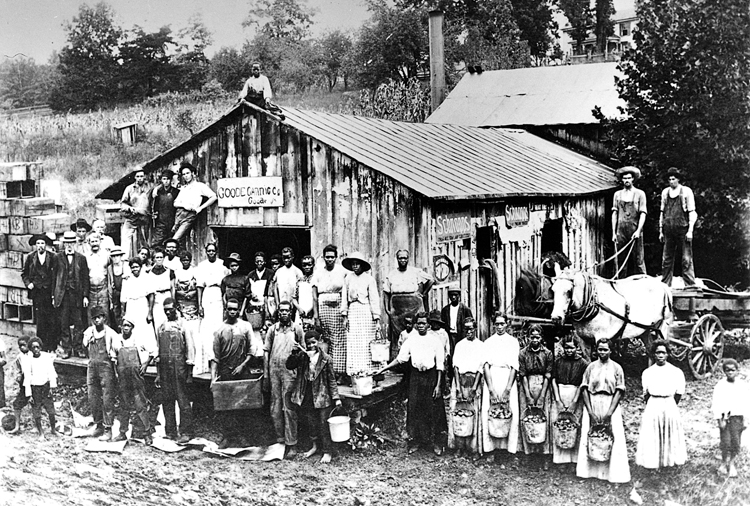

Norris goode’s art career was etched in stone. When he was ten, labels for his family’s tomato cannery—SMITH MOUNTAIN BRAND TOMATOES, PACKED BY GOODE BROTHERS, HUDDLESTON, VIRGINIA—were printed from limestone slabs at the nearby Piedmont Label Company using the German process of lithography. After high school, Piedmont Label was the only place Goode, an aspiring artist, went to look for work.

In the 1960s, Piedmont Label boasted a booming art department, distinct for its corner of southwest Virginia. Locals describe an era lifted from an episode of Mad Men, when drinks flowed (at least on Fridays) and artists drove fine cars (for Goode, that meant a sleek Volkswagen Karmann Ghia). “These guys thought they were rock stars,” says Bethany Worley, who recently curated “Virginia’s Forgotten Canneries: A History in Labels” at the Blue Ridge Institute & Museum at Ferrum College.

In the 1960s, Piedmont Label boasted a booming art department, distinct for its corner of southwest Virginia. Locals describe an era lifted from an episode of Mad Men, when drinks flowed (at least on Fridays) and artists drove fine cars (for Goode, that meant a sleek Volkswagen Karmann Ghia). “These guys thought they were rock stars,” says Bethany Worley, who recently curated “Virginia’s Forgotten Canneries: A History in Labels” at the Blue Ridge Institute & Museum at Ferrum College.

At the roots of both the local canning and art industries were tomatoes like those that grew on Goode’s family farm and the farms of his neighbors. During the first half of the twentieth century, the fruit prospered among the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. To deal with that abundance, many farmers established community canneries to pack tomatoes, which bruised easily and were otherwise difficult to store or ship. The need to mark or market them followed. Initially, farmers scribbled on generic labels. But in 1919, the Piedmont Label Company formed to serve some 90 tomato canneries in Bedford County and 193 in neighboring Botetourt County, creating bright labels that stood out on shelves—a feature that became increasingly important as supermarkets started to replace corner markets in the 1930s. Early labels included elaborate scenes of workers plucking fruits from fields, realistic renditions of homeplaces, stately livestock, and recipes printed in bold fonts. The label for Pride of Virginia Brand Herring Roe provides instructions for roe cakes—A NICE LUNCHEON DISH. But tomato images dominated.

“When I first went there, we were doing quite a few tomato labels, but then the tomato canneries started diminishing within Bedford County,” says Goode. “When I left, we were making more tomato labels for canneries in Indiana than we were in Bedford County.” Goode blames blight and other diseases for decimating local tomato production and canning. But industrial advances in refrigeration and transportation also changed the market, as farmers found new outlets for their produce.

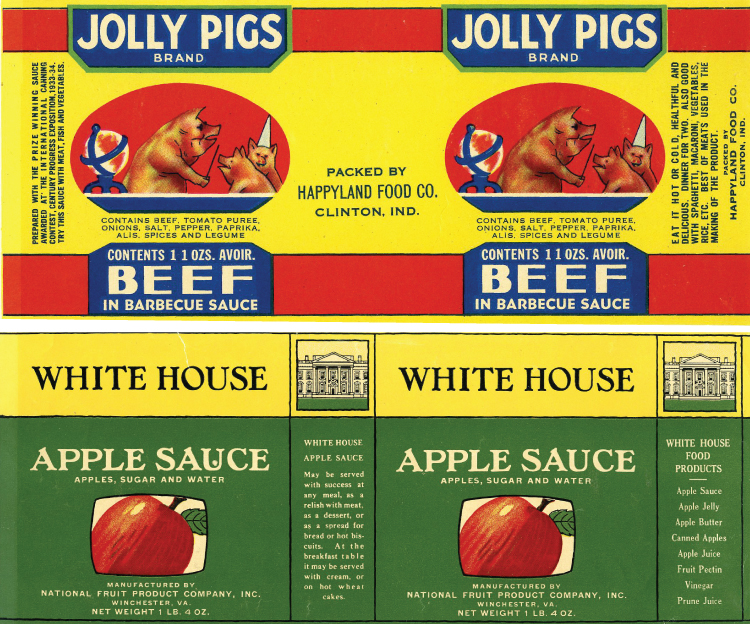

If something could be canned, Piedmont could label it: Brunswick stew from Georgia, oysters from Mississippi, gumbo from Louisiana, black-eyed peas from Tennessee, pet food from Washington, D.C.

With the decline of the local industry, Piedmont Label Company looked for new outlets, too. If something could be canned, Piedmont could label it: Brunswick stew from Georgia, oysters from Mississippi, gumbo from Louisiana, black-eyed peas from Tennessee, pet food from Washington, D.C. (THE CAPITOL FOOD FOR YOUR DOG AND CAT), and spaghetti gravy with peas from California. If it couldn’t be canned—bubble gum, brooms, and long underwear—Piedmont could, and did, label that, too.

This diversity drove endless opportunity for artwork, attracting creatives to a remote pocket of Virginia. Goode, who joined Piedmont in 1955 after studying at the Richmond Professional Institute (RPI) and serving in the Navy, was the only true local on the team. Others, many of whom also studied at RPI, came from Montana, North Carolina, and Germany. In Piedmont’s artistic heyday of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, the company retained eight artists on staff at any given time, not including typesetters and strippers—a group of women who combined four-color filmstrips for printing. “Not as we think of strippers today,” Goode clarifies.

Smyth Companies, which purchased the Piedmont name in 1988, now prints approximately 2.5 billion labels per year. In the factory’s entryway, three shelves display Smyth labels, including Clorox stain remover with color booster, Goya coconut milk, Mazola corn oil, Texas Pete hot sauce, Bush’s navy beans, and Valvoline synthetic-blend motor oil. According to Dora Gaither, who started at the company as an artist and who now works in human resources, only one to two artists remain on staff. In-house brand designers or outside design firms create the artwork for most labels on a computer. Goode, who retired from Smyth in 1997, oversaw that transition. He jokes that his trajectory spanned from the stone age, when lithographers printed from stone blocks, to the digital age, when computers took over.

Goode, whose office nicknames included “Goode the Dude” and “Goad the Toad,” spent most of his career in what he deems the film era, learning largely by trial and error how to style food for photographing. He counts as a triumph painting green beans with glycerin to make them shine. On the second floor of the sprawling Smyth factory in downtown Bedford, Goode’s studio stands unused: a small kitchen with a yellow stove, white cabinets, and a black-and-white checkered floor. In the center, colored rolls of paper, once unfurled as backdrops, now yellowing with age, frame an oversized, accordioned Deardorff camera. Until recently, a neighboring room housed files of film, mostly hand-labeled. One “S” drawer spanned SHRIMP to SAUSAGES, VIENNA. The Library of Virginia recently acquired those negatives, along with hundreds of glass slides.

The Blue Ridge Institute & Museum counts thousands of original labels in its files. Arranged state-by-state and county-by-county, the labels on file are at turns hilarious, weird, beautiful, nostalgic, and outright racist: a squirrel snacks on a canned stalk of celery; a beaming (perhaps radioactive) blue rod pulses next to a tomato for the Blue Steel brand; a blushing Miss-Lou embraces the states of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama on a can of pimientos; mammy figures smile with blackberries and Brunswick stew alike; and a black man serves himself an oyster that bears a hateful slur on its shell (and in its brand name).

Rifling the archives, place names—as small as Cahas Mountain, Virginia, and as big as Los Angeles, California—prove as curious and compelling as the artwork. Worley recalls a family from Idaho who traveled to the exhibition opening to map their roots on a label. Forget the Big Apple. For Goode and other artists and farmers, opportunity was just around the bend in Bedford, Virginia—for a brief moment, the Big Tomato.