Recipes in Black and White Does a cookbook have the power to heal?

by Michael Graff

The little cookbook entered the world in 2018, edited by a black professor and a white author, collected from members of a white church and a black church, maybe a peacemaker or maybe a disrupter, maybe too late or maybe right on time, but definitely in the right place.

Wilmington, North Carolina, should be the most prosperous city for African Americans in the United States today. More than a century ago, it stood as an example of successful Reconstruction, integrated and proud along the Cape Fear River near the state’s southeastern coast. It was North Carolina’s largest city, with more black residents than white residents. One of the country’s few black-owned newspapers published here. Black businesspeople owned ten of Wilmington’s eleven restaurants, and the black male literacy rate was higher than that of white males.

Now, the most visible reminder of those times stands on a bluff at the intersection of Third and Davis streets. Six bronze oars rise in 1898 Monument and Memorial Park to honor the victims of the only coup d’état to take place on United States soil, when murderous white men overthrew the elected local government and wiped away three decades of progress in a single day.

That day, November 10, 1898, white supremacists lynched dozens or more black people and burned the black-owned newspaper. Some accounts put the number killed at eleven; others say as many as 250. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery lists twenty-two lynching victims that day on the weathered-steel monument for New Hanover County—thirteen named, and nine inscribed as unknown.

It’s the most reprehensible event in the city’s history, and it was, for the white terrorists, brutally effective. Black residents fled inland; most never returned. The murderers took control. Their leader, a former congressman named Alfred Moore Waddell, who’d fallen on hard financial times and had boasted of his mission to “choke the current of the Cape Fear River” with black corpses, became the mayor. Afterward, he postured as a reluctant leader called to carry out a necessary mission. Indeed, several prominent North Carolina families supported the coup, including Rebecca Cameron, a novelist who wrote to Waddell: “There is a time to kill. Let it be buckshot and let it be at close range.”

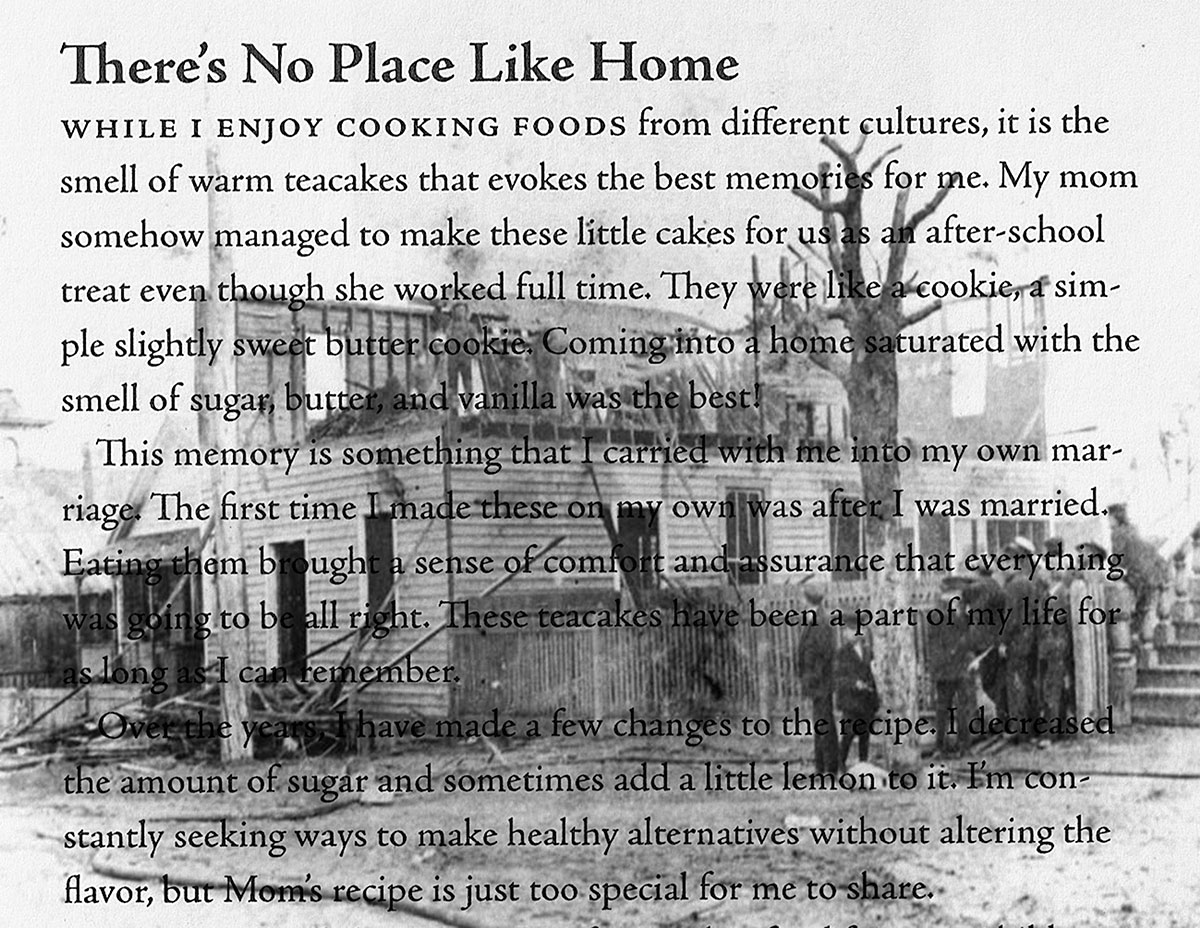

The first shots of the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 rang out at this intersection. Two white X marks drawn on the image by an eyewitness mark where the first two African Americans died.

Empowered whites reframed the coup as the Wilmington Race Riot, insinuating that there were bad people on both sides, as if the black victims shared blame for the violence. Schools across the state referred to it that way for decades, as did encyclopedias of North Carolina history. Only since the 2000s has the more honest name—the Wilmington Massacre of 1898—become mainstream. The state’s largest newspapers, the Raleigh News & Observer and The Charlotte Observer, apologized in 2006 for their editorials that helped incite and defend the violence, 108 years too late.

It’s hard to trace where black families scattered throughout southeastern North Carolina that November. One hundred twenty-one years later, people of color make up a significant portion of the area’s population, but have comparatively little power and wealth.

A little cookbook cannot heal that.

Tammy’s mom’s cornbread cannot heal that.

Mary’s banana cake cannot heal that.

Danyce’s baked flounder cannot heal that.

Cookbooks don’t have that kind of power, but they can highlight a community’s ambitions and project its unified beliefs. And if you stop there, Memories, Molasses & More, containing more than forty recipes from members of the historically black Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church and historically white Winter Park Baptist, achieves its mission.

Cookbooks can highlight a community’s ambitions and project its unified beliefs.

Novelist and professor Clyde Edgerton, from Winter Park, and retired professor Dr. Deborah Brunson, from Macedonia, came up with the idea for the book in 2014, when they were colleagues at UNC-Wilmington. They brought in Peggy Price, a retired high school English teacher and former student of Edgerton’s, to do the important work of collecting the story behind each dish.

The recipes and as-told-to essays form something modest but profound: In a city whose history has been defined by segregationists, the most segregated time of the week remains Sunday morning, which means the most segregated local literature is probably church cookbooks. In these pages, though, the parishioners share their kitchens and most personal dishes, one next to the other.

As I read the book this spring, I thought of all the ways I’ve seen people try to use food to bring people from different backgrounds together.

I’ve lived in six North Carolina cities, reported from every military base and estuary and most of the mountaintops; I’ve visited all 100 counties and eaten meals in most of them, and I married a Charlotte native on the grounds of the state’s first art museum. My love for North Carolina is, like most love, complicated. Here, people will proudly tell me that European settlers once called the North Carolina “the goodliest land” and “the pleasantest place,” and they’ll recite the state motto, esse quam videri (“To be, rather than to seem”), but in the same breath they’ll call a massacre a race riot.

On the last Wednesday of each month, I eat breakfast with a group of thirty to forty men who hold various leadership positions in Charlotte, about four hours west of Wilmington. We meet under the banner of “building trust across race and culture,” and we’re an offshoot of a women’s organization that started with a similar mission several years earlier. Most months, we’re evenly split among black men and white men, with a handful of Latinos. Some are banking legends, media presidents, and community organizers.

We’ve been doing this since the police shooting of a black man led to protests and riots in Charlotte’s streets in September 2016. Recently we started moving the breakfasts to different neighborhoods each month. Over biscuits and casseroles and coffee, we’ve discussed everything from Confederate monuments to jobs, propelled political careers and raised money for affordable housing, and had more personal moments where we share the words we heard as children about people from different races.

Often, it seems that our sharpest division is not race but age. For the older men, a breakfast conversation provides a candid space to reflect and rethink a lifetime with racism as a backdrop.

The younger guys are more urgent: Great talk, but now, what do we DO?

I’ll be forty in December, just old enough and just young enough to believe the tension is good. After nearly twenty years as a writer here, and after attending countless breakfasts and international festivals and supper events and lunchtime panel discussions aimed at “celebrating our differences,” I do wonder: What have they accomplished? Charlottesville still happened one state to the north. Charleston still happened one state to the south. And in an arena in eastern North Carolina this summer, about one hundred miles from Wilmington, thousands of people still attended a presidential campaign rally and unleashed a chant aimed at a foreign-born United States Congresswoman: “Send her back.”

Under those clouds and concerns, I leave my house in Charlotte one Friday morning to spend a weekend in Wilmington, to see what, if anything, can come from a little cookbook.

On the first day, Deborah Brunson’s husband, Bernard Brunson, shows me the Wilmington he remembers.

“Fourth Street was the hub of the black experience,” he says. We’re near downtown, four streets east of the riverfront. “When I grew up this was all I knew.”

Bernard, age sixty-nine, is a US Army veteran who grew up here and attended all-black schools until the eleventh grade, when integration sent him to New Hanover High.

He joined the Army at nineteen and visited thirteen countries before coming home to stay. He fell for Deborah in 1992, not long after she moved here. A friend invited her to a cookout to meet a potential date; that man didn’t come, but Bernard was there, and they married two years later. They love Wilmington, but that love is complicated. In the same car ride, Bernard tells stories of catching a fifty-five-pound amberjack off Johnnie Mercer’s Pier, and then others of the closed-down, all-black Williston High School and James Walker Memorial Hospital.

At times he talks so fast about what used to be that I can’t keep up.

“This was a boxing gym and now it’s a bar.”

“This was Harris barbershop.”

“This was a bakery, ABC Bakery,” he says, “and it’s been converted into apartments.”

“All of this that you see around you was 99 percent African American. Now, because of the economy and everything, a lot of things have been taken over. And now it’s more whites.”

He pauses and attempts to soften his description.

“It’s a blended area.”

But his words “taken over,” hang in the car. In Wilmington, he knows, the phrase holds meaning.

Manhattan Park, a gathering place for Wilmington’s African American community, was severely damaged during the Massacre of 1898.

For every picture of Spanish moss–draped beauty here, there are historical images of people like the Wilmington Ten, nine men of color and a white woman wrongfully convicted in 1971 of firebombing a white-owned grocery store. Recently released notes show that the white prosecutor on that case made notes like “KKK? … good” while selecting a panel of ten white and two black jurors.

Two cemeteries sitting side by side off of Rankin Street might be the clearest illustration of Wilmington’s racist past. Brunson turns the car toward the first, Pine Forest, enclosed by a bent and broken chain-link fence. It includes graves of the country’s first professionally trained African American architect and North Carolina’s first African American lawyer. Several Wilmingtonians from the late 1800s are buried there in unnamed graves. Maybe they were store owners or musicians. We will never know.

Bernard turns around, makes two rights and heads into Oakdale, the white cemetery next door, fenced in wrought iron and sheltered by magnolias.

“That’s how deep the system ran,” Deborah says from the back seat. “Literally from the cradle to the grave.”

Bernard tells me that his sister, who died at birth, is buried at Pine Forest.

I ask him what he would think if, by chance, one of his relatives wanted to be buried at Oakdale.

“Personally, it wouldn’t affect me,” he says, pausing to look out the window at the pristine grounds of Oakdale, “but that would not be my first choice.”

Clyde Edgerton, the author of twelve books and a former Guggenheim Fellow, lives in a 1953 ranch house about two miles from those cemeteries. I visit him on Saturday afternoon. He’s sitting on a bench on his back porch dropping red beans and rice on his shirt while talking about racial justice with his mouth full.

“Other Americans see the South as the cradle of racism,” he says, “so it’s not a big jump to think that the cradle of racism might hold some of the solutions.”

He drifts between big, systemic troubles in America, and smaller, local problems in Wilmington. He’s been raising hell with the school board for four years about admissions practices in a Spanish-language immersion program. The program admitted white children at a much higher rate than black children in its early days. Edgerton believes the problem persists; the school board says it’s fixed. He sparred with the superintendent in the Wilmington Star-News editorial pages in April.

Now in his seventies, Edgerton faces a question familiar to many white progressives from his era: He’s been an advocate for civil rights throughout his adult life, but did he do enough? In the cafeteria at UNC-Chapel Hill in the 1960s, his roommate asked him what he’d do if the new black students sat down next to them. The roommate said he’d leave; Edgerton said he’d eat with them. At the time, that might have been notable—as it was in 2008, when Edgerton hosted a big fundraiser for then-candidate Barack Obama in his backyard.

But in the past four or five years, he’s come to a hard-stop realization: “You can’t have racial reconciliation without racial justice.”

Now in his seventies, Edgerton faces a question familiar to many white progressives from his era: Did he do enough?

Deborah Brunson grew up in Washington, DC, in the 1950s. Her mother was from Alabama and her dad from South Carolina. They’d moved north during the Great Migration. They didn’t have the chance to advance past grade school, but they were avid readers, and they made sure their children knew the importance of the Civil Rights Movement.

Brunson remembers sitting with her parents at dinner to talk about accomplishments and setbacks over potato salad and collards. Her mother’s macaroni and cheese recipe appears in the cookbook.

Brunson graduated from Howard University, earned a master’s in communication from the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now UL-Lafayette), and a doctorate at Florida State. At that last stop, she learned about 1898 in Wilmington. She landed a job at UNC-Wilmington in 1991 and spent nearly twenty-seven years teaching courses on interracial communication, communication theory, and community and interracial dialogue.

A few years older than Brunson, Edgerton grew up outside of Durham, North Carolina. His grandparents were sharecroppers. After college, in the summer of 1966, he took a position as the head counselor in the Chapel Hill chapter of Upward Bound, a federally funded program aimed at giving low-income students better opportunities to attend college. He says about 90 percent of the counselors were black, and the person who hired him, a black woman, joked that when she saw his application she said, “Oh, here’s a little white one; we better let him in.”

Edgerton served in the Air Force in Vietnam before becoming the “Mark Twain of North Carolina,” as his most devoted fans call him. His books, starting with Raney (1985), often use humor to expose contradictions in Southern and Christian customs, and the impurities of institutions such as, say, universities. Through fiction, he’s fearlessly honest about the places where he grew up and worked.

After he met Brunson in 2014, he invited her to speak to one of his classes, and they became friends. They learned that they were members of sister churches—Edgerton at Winter Park, Brunson at Macedonia. The churches had traded pulpits a few times over the years, and some members had spent a Sunday or two in the other church. Edgerton, an accomplished banjo player, was drawn to the music at Macedonia.

By then, the idea of racial justice consumed Edgerton. He thought of his childhood in rural North Carolina and how the black people in his segregated community were invisible to him, except when they shopped for groceries. Food, he thought, was the one thing they must have in common. And that’s how Memories, Molasses & More came to be. Edgerton and Brunson arranged for UNC-Wilmington to publish and print a few hundred copies to sell to the churches.

But in the past four or five years, he’s come to a hard-stop realization: “You can’t have racial reconciliation without racial justice.”

For the project to reach a wider audience, they needed more than recipes. They wanted to take readers into the contributors’ homes, for holidays and ordinary days, and desegregate dinner tables in print.

Peggy Price interviewed most of the contributors personally. Some stories go into great detail. Dorotha Cahill’s tale about her cranberry salad, for instance, takes us to her Oklahoma childhood home during the Depression, when her mother would feed “hobos” out of her back door. Clif Harris writes of his mother, Mary Willie Yelton Harris, who brought her “Mountain Pie” down from the hills when she moved from Appalachia to eastern North Carolina in 1918. Gloria Dutch’s picnic potato salad is so good, she says, her mother and aunt argued over who taught her to make it. And Jessica Monroe offers a snapshot of life at James Walker Hospital during segregation. Her grandmother worked in the kitchen there, and the staff allowed Jessica to hang out after school while she waited for her mom or dad to pick her up.

Through stories like those, the book memorializes people and places that might otherwise be lost. Yet I did not find a single, direct mention of race or racism.

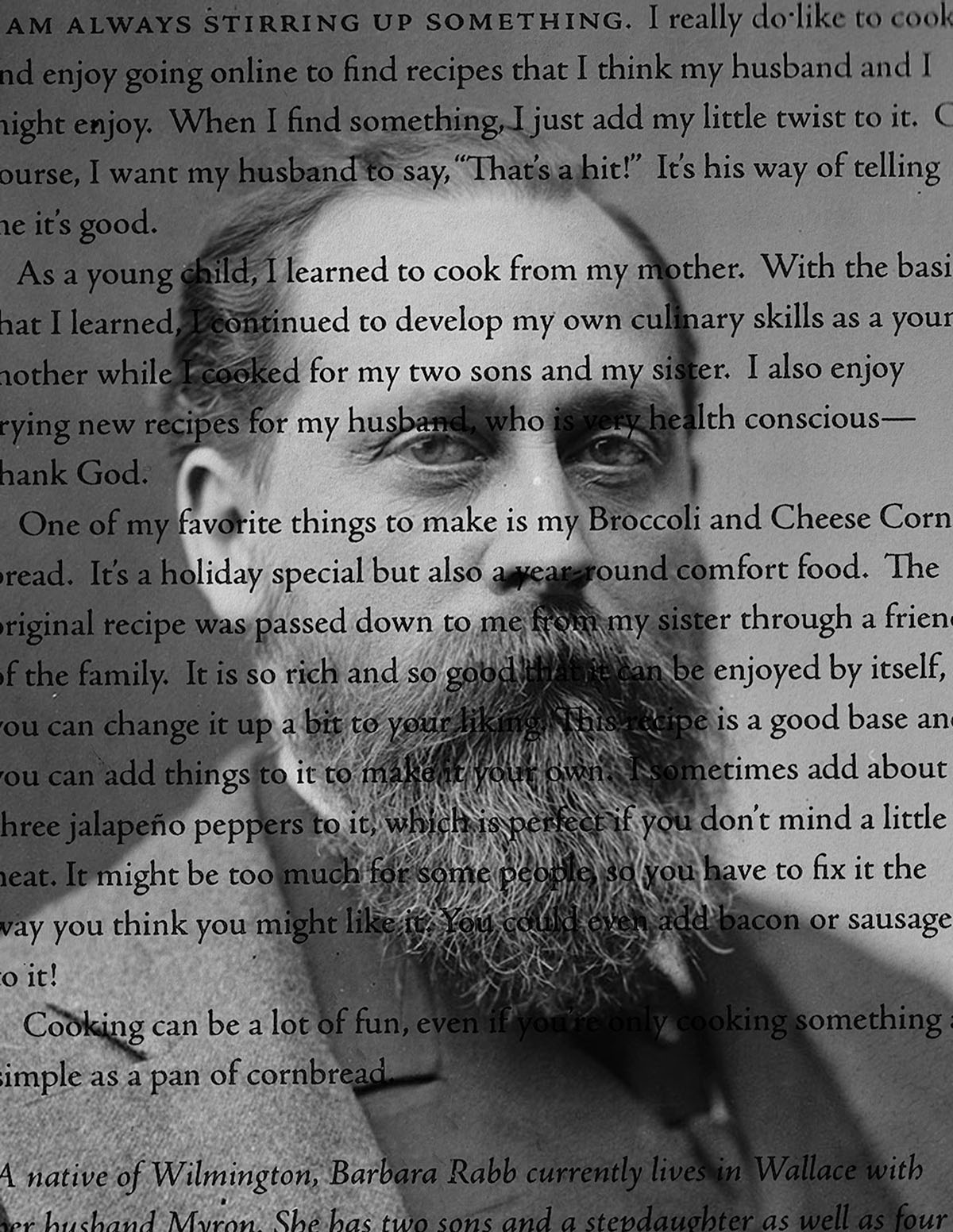

Alfred Moore Waddell, previously a United States congressman, became the mayor of Wilmington after the Massacre of 1898.

A colleague of mine in Charlotte runs workshops aimed at bridging racial gaps in the workplace. In his program, he explains that achieving trust between two people is a five-step process. The first step is getting to know each other, followed by finding a connection, relating to each other, sharing a common experience, and finally trusting each other. Submitting a recipe and a story for a cookbook fits more or less in the third stage. It’s an act of relating, but it’s a long way from trusting another human enough to address topics like racism.

For some, though—especially those who grew up in Jim Crow North Carolina—even sharing the stories is a big step.

Of course, they’re skeptical. Invitations to come together are hardly in short supply for people of color. The organizers are often well-meaning white people who want people to reconcile, but who, even in their invitation, reveal that they’d like it done on their terms.

“I can speak for white people—well, some white people,” Edgerton tells me. “They sit around and talk, and they leave and they feel better.” (Edgerton and I talked for nearly two hours about this on his porch that Saturday, and when I left, I felt pretty good.)

But then what?

Invitations to come together are hardly in short supply for people of color.

Brunson calls initiatives like the cookbook a “sensory involvement” in diversity. She means it’s a surface-level engagement—or, as my colleague in Charlotte says, part of the relationship-forming stage.

“This is wonderful,” Brunson says. “But how does it advance the quality of life if after I leave here, I have these encounters with the police? Or I can’t get a loan? Or a house? Or I’m dealing with issues with how my child is being treated at school. And I’m speaking as a person of color, and I think for people of color, that’s why there may be a hesitancy to step into these kinds of things. Because it’s like, OK, well, we’ve been here before. This’ll make people feel good for like fifteen minutes, and then, what has really changed?”

That’s what I came to Wilmington to ask, I tell Brunson and Edgerton. What has really changed?

It’s hard to quantify, they say. The book can be a piece of a resolution to the city’s long history of racism, but hardly the whole thing. And its importance depends as much on the reader’s perspective as on the words themselves.

Zach Hanner, a white man who directs the local theater company TheatreNOW, read it and decided to turn it into a stage production. Memories, Molasses & More, the theater version, ran during the late summer and early fall of 2018. Everyone who contributed a recipe was invited to attend, and most did.

The ninety-minute adaptation starts with white characters and black characters cooking separately and ends with them around a large table saying grace.

If only it were that simple.

On our driving tour of his hometown, Bernard Brunson’s last stop is the 1898 Memorial. He and Deborah walk up the brick walkway, past a patch of black-eyed Susans and wiregrass, and stand in front of the six vertical paddles.

The paddles are meant to symbolize water, its importance in spiritual beliefs in African culture, and how it is a symbol of purification, forgiveness, and renewal. So says the inscription. Another plaque tells the abridged story of the massacre.

On either side of the monument, about halfway down a semicircular walkway, are two meditation areas, named Peace Circle and Hope Circle. The memorial has become a gathering spot for rallies for everything from the National Day of Prayer to immigrant rights.

Deborah takes a seat in Hope Circle and looks up at the trees. Bernard stands on the hill with the paddles. We all remain quiet. It’s a solemn place.

Bernard points toward the highway and the bridge over the Cape Fear River. He tells me a chilling story that was passed down to him. Apparently, after white supremacists killed several black people along this road on November 10, 1898, they lined the streets with body parts of the deceased. Then, the whites gave the road a repugnant nickname. Bernard tells me the nickname, then asks me to not include it in the story.

“That’s something people don’t talk about,” he says. “There’s the truth and then there’s the truth.”

If I forget everything else from the trip, I’ll remember this moment. It’s as if Bernard wishes he could erase the words from my notepad, delete them from my tape recorder, and swallow them back down to a place where they’ll never come up again. If he were contributing to a cookbook, this would be just the kind of thing he’d edit out. By now we’ve spent most of the day together, riding around his beautiful and complicated hometown, eating crab cakes on the Intracoastal Waterway, telling stories about big fish and family. Still, some truths are too difficult to share because they’re too horrible to shed.

Michael Graff is a writer in Charlotte.