PACIFIC SOUL Stuck inside of Orange County with the Memphis cool again

by Gustavo Arellano (Gravy, Spring 2016)

“IT WASN’T MEMPHIS, BUT IT WAS WONDERFUL.”

A Kentuckian named William Spurgeon founded my adopted home of Santa Ana, California, in 1869. Magnolias bloom every spring around the Old Orange County Courthouse, planted there over a century ago by pioneers who brought with them the most fragrant memories of the states they left behind. Henry W. Head, the assembly member who represented the district when it seceded from Los Angeles County in 1889, served under General Nathan Bedford Forrest and fought at Shiloh.

A Kentuckian named William Spurgeon founded my adopted home of Santa Ana, California, in 1869. Magnolias bloom every spring around the Old Orange County Courthouse, planted there over a century ago by pioneers who brought with them the most fragrant memories of the states they left behind. Henry W. Head, the assembly member who represented the district when it seceded from Los Angeles County in 1889, served under General Nathan Bedford Forrest and fought at Shiloh.

Our connections to the South aren’t just moldering in the archives. For the past twenty years, Memphis has taught OC how to eat and drink and live well—not the city on the Mississippi River, but Memphis Café in Costa Mesa. Run since its debut by chef Diego Velasco, it’s one of the most influential restaurants in Orange County history. It introduced pan-Southern cuisine to us with its jambalaya, ribs, and mint juleps, ushered in the era of the celebrity chef in OC, and fostered a nascent music scene by bringing in DJs and bands that created a new national image for the region—a place USA Today would go on to call America’s “capital of cool.”

Here’s the funny thing: Memphis Café isn’t named after Memphis, Tennessee. It’s named after Memphis, an Italian arts and furniture collective from the 1980s that café co-owner Dan Bradley studied as an arts undergrad at the University of California-Los Angeles. And that Memphis, in turn, isn’t named after the city but rather “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” Bob Dylan’s seven-minute epic about…something, anything, except Memphis, Tennessee.

Southern culture has stood for many things, but this particular interpretation is a beautifully postmodern one: The idea of Memphis helped a Chicano from Southern California teach one of the squarest places in the U.S. how to be hip. Gimme a Hammond B-3 organ riff courtesy of Al Green, and let’s begin this tale…

Memphis Café is a squat, dark space with an open kitchen, a bar serving more than 100 whiskies, and a soundtrack that veers between 1980s new wave and yacht rock. It sits just south of the 405 Freeway, Costa Mesa’s own Big River. I’ve patronized the place for fifteen years now, drawn by Velasco’s California take on Southern standards. Popcorn shrimp fill tacos, pulled pork sits on Hawaiian rolls, and the po-boys come slathered in a Sriracha-spiked mayo. He can do a mean crawfish boil and a fine shrimp and grits, but Velasco—who, with perfectly tousled hair and an immaculate soul patch, looks more music producer than chef—doesn’t claim authenticity.

Memphis Café is a squat, dark space with an open kitchen, a bar serving more than 100 whiskies, and a soundtrack that veers between 1980s new wave and yacht rock. It sits just south of the 405 Freeway, Costa Mesa’s own Big River. I’ve patronized the place for fifteen years now, drawn by Velasco’s California take on Southern standards. Popcorn shrimp fill tacos, pulled pork sits on Hawaiian rolls, and the po-boys come slathered in a Sriracha-spiked mayo. He can do a mean crawfish boil and a fine shrimp and grits, but Velasco—who, with perfectly tousled hair and an immaculate soul patch, looks more music producer than chef—doesn’t claim authenticity.

“Whenever Southerners come in, I tell them my food is Southern cuisine for an Orange County demographic,” the forty-three-year-old says, almost apologetically. “I’m intimidated whenever a Southerner comes in! I tell them, ‘Before you throw the book at me, realize where we’re at. It’s a resemblance.’”

VELASCO’S CAREER IS A TESTAMENT TO THE SOUTH’S ETERNAL LURE.

Velasco’s career is a testament to the South’s eternal lure. He was raised by a single mother in the Mexican-American suburb of Montebello, on the outskirts of East Los Angeles. Velasco’s family worked in the Garment District in downtown LA, but young Diego quickly gravitated toward the kitchen. From a young age, he learned to love the holiday spectacle of food, especially Ash Wednesday for Mexicans, with its tortas de camarones (shrimp balls served in a red chile broth alongside cactus) and capirotada (bread pudding). “Seeing those traditions,” he says, “taught me about the importance of food to people beyond just eating.”

Velasco was introduced to Southern food at eighteen, while working at a hot-springs resort in Orange County. He connected with members of The Rebels, a New Orleans swamp-rock quartet who lived in a trailer on the property. They were the house band at a local roadhouse, the kind of joint where bikers broke bottles and swung pool cues. The group—one a shrimper, another a Houma Indian, another a Cajun—took the young cook under their wings.

“They had come to Southern California to make it big,” Velasco says. “But on their time off, all they did was cook—gumbo, black-eyed peas, sticky chicken. I remember once during a Super Bowl, they cooked like the dickens—dark and deep and soulful and haunting and awesome.”

Velasco was so moved by their food that he roomed with the band members for a year. Afterward, he made a pact with two friends: One would manage a restaurant to learn how to run one, another would find funding, and Velasco would leave business school at Cal State-Fullerton to enroll in the California Culinary Academy in San Francisco and learn “why the South cooked like that.”

He was an anomaly in those days, when most aspiring chefs in the West focused on French, Italian, California, and Pacific Rim cooking. But Velasco and his partners were undeterred. They opened Memphis Café in 1995, in an old dive bar.

“I remember thinking we were going to get squashed,” Velasco admits. Cuisine in OC in those days consisted of overpriced white-linen spots or chain restaurants—and definitely didn’t bother with regional American. “But we weren’t trying to do everything for everyone. We just did what we wanted to do.”

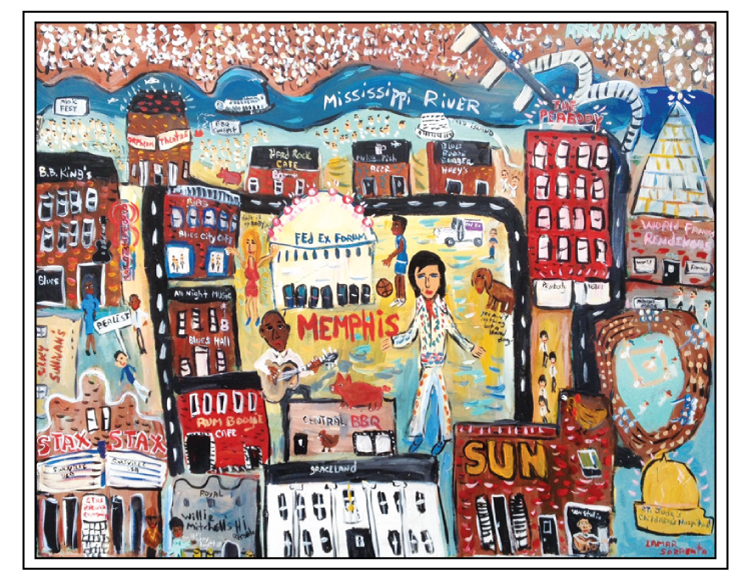

Memphis Café arrived at a seminal moment in Orange County history. In the 1990s, the notorious Stepford suburbia suddenly became a tastemaker for America’s youth, from music (No Doubt, Social Distortion, The Offspring) to fashion (Quiksilver, Vans, Oakley). Memphis Café became the crossroads for disparate scenes, in the same way its eponymous city could host Sun and Stax records, Elvis, Justin Timberlake, and Three Six Mafia, all drinking from the same replenishing well.

At the Costa Mesa mothership and its Santa Ana branch (my main watering hole), businessmen rubbed elbows with politicos, artists, hipsters, gang members, musicians, and immigrants. The Memphis bar program became the cocktail equivalent of a Bear Bryant coaching tree. Its alums now work at OC’s best restaurants, and they taught the county how to love old fashioneds and Manhattans.

Velasco sheepishly admits that he made his first trip to Memphis, Tennessee, only four years ago. Before that, he went by feel.

“It’s in the ambiance,” he says. “It’s professional but friendly. More laid-back. It’s about how we treat people.”

And Velasco isn’t slowing down. He recently introduced jalapeño shrimp and grits, covered in red-eye gravy and a thick slab of country ham. “Even twenty years later, Southern food still excites me,” he says. “And I’m just beginning to learn.”

CULTURAL APPROPRIATION IS A TRICKY THING.

Cultural appropriation is a tricky thing. OC’s Memphis may not be a simulacrum of the Bluff City, but it exemplifies its best qualities: the funkiness of the Bar-Kays, the heaping portions at any rib shack, the camaraderie and hospitality tourists feel at Graceland. Proud to be of the South, whether in the Volunteer State or in the Land of Real Housewives.

Cultural appropriation is a tricky thing. OC’s Memphis may not be a simulacrum of the Bluff City, but it exemplifies its best qualities: the funkiness of the Bar-Kays, the heaping portions at any rib shack, the camaraderie and hospitality tourists feel at Graceland. Proud to be of the South, whether in the Volunteer State or in the Land of Real Housewives.

Years ago, a friend of mine—a Memphis native who, in yet another awesome cross-cultural turn, now runs one of the most influential Chicano presses in the country from El Paso—was in Orange County and needed a restaurant recommendation. I meekly suggested Memphis. “An OC restaurant named after Memphis?” he snickered. But he went.

“It wasn’t Memphis,” he wrote the following day, “but it was wonderful.”

Gustavo Arellano is the editor of OC Weekly and Gravy’s columnist. Photos by Delilah Snell.