Pimento Cheese in a Parka What southern means to Chicago

by John Kessler (Gravy, Summer 2016)

For my first winter in Chicago, I bought a goose-down parka with a hood trimmed in coyote fur. Whenever I came home from walking the dog in the snow at night, the hall mirror reflected me as a dark lump topped by a pair of freezing, bulging eyeballs set in a ring of fur. I looked like Kenny from South Park, if not Death himself in a cowl.

I expected to miss Southern food in my new hometown. I did not expect to spy a funhouse version of it around every corner.

A Chicago winter can feel like end-times to a Southern transplant. I arrived to join my wife, who had begun a job a year ago at the University of Chicago. Before that, I had worked for nearly two decades as a columnist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. In Atlanta, I ate my way Southern. During that time, I documented a sea change in the city’s food culture, as the regional standard bearers turned from cafeterias and all-you-can-eat buffets to restaurants directed by studious chefs. When I speak of chefs who supported area farmers and researched foodways, it now sounds cliché, but goddamn if Scott Peacock’s fried chicken and vegetable plate at Watershed circa 2005 didn’t change my world. As the city came of age, so did I.

I expected to miss Southern food in my new hometown. I did not expect to spy a funhouse version of it around every corner. Chicago is in the throes of an energetic (and, honestly, slightly bananas) infatuation with the South. The word “Southern” has become a capacious vessel into which hungry people slop buckets of desire and nostalgia. It is, yes, fried things. And bourbon cocktails and hockey-puck biscuits (go Blackhawks!). It is also more. Random burgers here earn the sobriquet Southern. Chicken tenders are Southern. Pimento cheese Southernizes furls of cavatappi pasta.

“People here love that whole hillbilly chickenshit attitude,” says Art Smith, the former personal chef to Oprah Winfrey whose Chicago restaurant, Table Fifty-Two, helped pave the way for this current cohort of Bubba Come Latelys. He’s right. I have seen completely nonsensical “North Carolina pulled pork po-boys” and “Nashville hot wings” at restaurants. One menu boasted “Georgia lake prawns.” Really? I’m going to have to look for those trawlers on Lake Lanier next time I go back.

My family and I settled in the Bucktown neighborhood, on the ground floor of the former Wojciechowski Funeral Home, which served as a major triage center during the 1918 flu pandemic. We liked the old bones and history. The day we toured the building and put in an offer, we ate brunch, on our realtor’s suggestion, at a nearby restaurant called The Southern.

A dark retreat for the hungover, The Southern stocked bourbon behind the bar and featured a sign lettered in the same font as the Gone with the Wind movie credits. The menu was pure redonkulosity—an eggs Benedict variation made with biscuits and fried boneless chicken, a “Southern Reuben” of braised brisket and pimento remoulade. I dug into a pile of Breakfast Macaroni, tossed with curds of scrambled eggs and slivers of bacon. It didn’t taste too bad for a dish that, posted to Instagram, would have recalled a medical textbook image. Despite its name, The Southern, with its day drinkers, hefty sandwiches, trendy avocado toast, and indifference to seasonal vegetables, seemed so very Chicago to me. Restaurants like these are Southern in the way that The Mikado serves as a meditation on Japanese culture.

The word “Southern” has become a capacious vessel into which hungry people slop buckets of desire and nostalgia.

A spot in nearby Lakeview, Wishbone, employs a flying-chicken decorative theme (think scores of soaring chickens painted on rafters and soffits overhead, like a comic vision of Hitchcock’s The Birds) and serves what it calls “Southern cooking for thinking people.” The implication is not that inchoate emotions typically rule diners from the former Confederacy. Instead, the motto is meant to convey that the kitchen prepares the food with supposedly healthy ingredients. The Wishbone menu throws around descriptors like “Asheville” to indicate blue cheese and honey-mustard dressing in a salad. And it takes liberties with established dishes. Hoppin’ John translates as a bottomless bowl of black beans and brown rice under a thick cap of melted cheddar cheese. Bless their hearts.

At Buck’s in Wicker Park, the tagline is “Southern fried funk” and the website promises “a taste of ‘Down South, Up North.’” It is a place of lounge seating, grandma china, buckets of fried chicken, Cheerwine floats, ironic hospitality-pineapple wallpaper, and hot biscuits served with forlorn little plastic cups of pimento cheese. Look at the booze menu, though, and you couldn’t be anywhere but Chicago. The signature “Bucknasty” brings a Schlitz tallboy and a shot of Malört, the locally beloved bitter liqueur that tastes like Fernet-Branca’s evil twin. This is food and drink designed to help you endure the cold.

A spot in nearby Lakeview, Wishbone, employs a flying-chicken decorative theme and serves what it calls “Southern cooking for thinking people.”

A restaurant called Dixie will soon open five blocks from my home. The name gives me pause, as does chef-owner Charlie McKenna’s talk of taking design inspiration from “the antebellum South.” McKenna, a South Carolinian who worked in high-end restaurants before opening a well-liked local barbecue spot, Lillie’s Q, has strong ideas about the kind of South that Chicago wants. That vision includes cocktails and non-traditional small plates, such as Nashville hot sweetbreads with white bread sauce. (Itself a riff on hot chicken and the white bread that traditionally accompanies it, a version of the dish first appeared at The Catbird Seat in Nashville.)

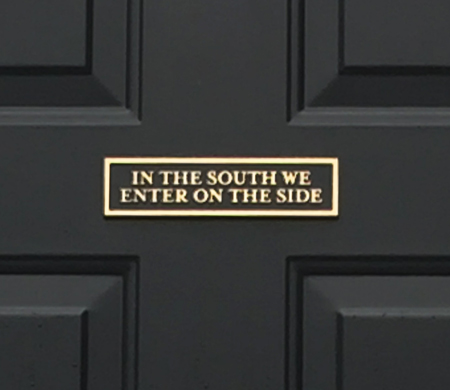

I walked to Dixie in an early-April snowstorm that swirled to a near whiteout before blowing off. McKenna met me at the site on a hopping restaurant block. Tucked alongside a French bistro and a Japanese izakaya, built as a typical A-frame brick house, the Dixie space had once been the Michelin-starred restaurant Takashi. McKenna gutted the building and poured a raised concrete front porch for rocking chairs to face the busy street. Inspired by the piazzas of Charleston architecture, he tucked the entrance at the side of the building, halfway down a narrow alley. (“We’re thinking of putting up a sign that reads, ‘In the South we enter on the side,’” said Nick Bowers, head of the architecture and design firm overseeing the buildout.)

I tried to ask McKenna about the words “Dixie” and “antebellum.” To my ears, both are charged with layers of complicated meanings. I had to push, perhaps a little too stridently, the question of slavery. I could tell this wasn’t where McKenna expected the conversation to go.

“For me, the name Dixie kind of represents the South as a whole,” he said, pausing to find the right tone. “You know, it’s where I came from. I’m going to be taking a lot of the food and ingredients the slaves brought over and celebrating it in a better light. It’s just a word. It’s the people who make the South great.”

I pursued the question later with Bowers, who had been researching antebellum color schemes (“greens, blues, reds: bold colors”) and design accents (“brushed brass and gold”). Historical photos, purchased from a restaurant-prop supplier, would blanket the side walls. I asked if they planned to vet the pictures to find out if they depicted slave owners. I asked if any of the pictures would include black faces. Bowers grew uncomfortable, saying, “Obviously slavery is not a focus to the restaurant. If we know it’s somebody who was negatively impacting the South, we wouldn’t use that image.”

I asked if they planned to vet the pictures to find out if they depicted slave owners. I asked if any of the pictures would include black faces.

I wonder if Dixie will be a place where no guest will know the tune to whistle it. I am looking forward to those sweetbreads, and when McKenna talks about serving country ham and cheese straws at the bar, the very words thrill me to my toes. But with its rocking chairs and brushed brass, Dixie promises to thematize the pre–Civil War South for a curious dining public, much as the lace curtains, art nouveau lettering and pressed tin ceiling of its neighbor evokes the idealized Paris of a hundred years ago. Southern food and Southern history belong to all of us, and after living in Atlanta, I can’t separate them.

Paul Fehribach, the Indiana native who runs the city’s best and most thoughtful Southern restaurant, Big Jones, thinks Southern cooking resonates because it is, at heart, American country cooking. He says that’s why you see the word “Southern” on Chicago restaurants as often as (if not more than) you see “Midwestern.” “Southern” translates, in the minds of diners, as a kind of idealized home cooking.

Fehribach, who builds historical research into his recipes, serves collard-green sandwiches on cornbread, house-cured tasso ham, Sally Lunn bread, Memphis-style barbecue, and Edna Lewis–inspired fried chicken that earns national praise. His menu surveys the subregions of the South in their fractured glory, but it all feels of a piece.

All of these restaurants are on the predominately white North Side of the city. Most black Chicagoans who can trace their roots to the South and to the Great Migration make their homes on the South Side. My own family began its Chicago adventure last summer in the South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park, a diverse community where we lived for a couple of months in University of Chicago housing. Our flat was in a dark, stately Renaissance-revival apartment complex that made me think of Rosemary’s Baby. It has, through the years, apparently housed more Nobel laureates than any building in the country.

![]() There were no “Southern” restaurants nearby, but the local market stocked produce I recognized from Georgia, including okra and scuppernongs. Once when I returned home laden with groceries and couldn’t open the massive wrought-iron grille door, Belinda Clark, the African American woman working the front desk that day, leapt up to help me. “Now what are you going to do with those greens?” she laughed, looking into my shopping bag. I explained that I cooked a good, if non-traditional, pot of collards. To prove my bona fides, I let it slip that I had just moved from Georgia. Clark’s face lit up. Her grandparents emigrated from Alabama and Mississippi. The South fueled her imagination. She and her husband hoped to take a long driving vacation once they could get the time.

There were no “Southern” restaurants nearby, but the local market stocked produce I recognized from Georgia, including okra and scuppernongs. Once when I returned home laden with groceries and couldn’t open the massive wrought-iron grille door, Belinda Clark, the African American woman working the front desk that day, leapt up to help me. “Now what are you going to do with those greens?” she laughed, looking into my shopping bag. I explained that I cooked a good, if non-traditional, pot of collards. To prove my bona fides, I let it slip that I had just moved from Georgia. Clark’s face lit up. Her grandparents emigrated from Alabama and Mississippi. The South fueled her imagination. She and her husband hoped to take a long driving vacation once they could get the time.

Clark grew tomatoes, collard greens, beans, peas, and okra in her home garden. Some years she wouldn’t plant until May for fear of a frost. Her husband hunted to stock the freezer. They loved fishing together. Her cooking was not that different from her grandmother’s. For the next couple of months, we talked about food every time our paths crossed. She helped me deal with the dull ache of homesickness and the equally insistent ache for okra.

Home. That’s surely what I miss when I miss Southern food. I get it.

Home. That’s surely what I miss when I miss Southern food. I get it. When I mutter that the grits at some trendy brunch place suck, I’m also saying that it shouldn’t be 42 degrees outside in May, that I miss my backyard garden and my friends, and that I fret I will never experience in Chicago that sense of food and place, of season and cook, that was the soul of every meal at Cakes & Ale in Decatur.

Then again, sometimes I wonder if that’s what everyone here looks for in Southern food, even if they’ve never been to the South. Maybe it’s part of our shared cultural memory, our American identity. Or perhaps Southern is the new Thai—a crowd-pleaser with a whiff of the exotic.

I’m cooking more Southern food now. I keep Anson Mills grits in the freezer, and I cook a pot of greens whenever I find any that look half good. And now that I live on the North Side, I can walk a few blocks for a pimento cheese and fried green tomato biscuit sandwich. It’s an unholy trinity, let me tell you. I sometimes want to stand on my bar stool and yell to all Chicago, “People! Cold pimento cheese and hot biscuits: not a thing!” Then again, on a chilly May night, it doesn’t taste too bad.

Online Exclusive Kessler Dines at Dixie

When I began surveying Southern restaurants in Chicago, I had anticipated much of the article would turn around a meal at Dixie. This restaurant’s opening had been so anticipated, and chef/owner Charlie McKenna seemed eager to move the local notion of Southern dining beyond American folk cooking into a more romantic realm of $12 craft cocktails and heirloom tomatoes. But the never unexpected construction and licensing delays nixed that idea, so I instead toured a construction site and interviewed the designer.

The restaurant is around the corner from my house, so I had the opportunity to watch the buildout. I’d chat with the workmen as they replaced the facade of this old A-frame house and poured a slab concrete front porch. A Pokémon Go gym “opened” a couple of doors down, and I often hovered outside doing virtual battle and witnessed the finishing touches. The building got a bright coat of whitewash and a gold “Dixie” sign lettered in the scrolling calligraphy of a wedding invitation. Some rocking chairs appeared on the porch and were, in short order, lashed to the railing with chain link. (I thought fondly of the old Bobby and June’s Kountry Kitchen in Atlanta, which has its own chained rockers.) Eventually a small plaque appeared on the apparent front door that read “In the South We Enter on the Side.” This was a reference to the piazzas of Charleston single houses, though when we visited soon after it opened, the feeling was decidedly more that of a speakeasy than an invitation to Nathalie Dupree’s.

Down a narrow alley between Dixie and its neighbor, we went to the side entrance behind an industrial steel door. Inside, a lot of energy was packed into a small space, with a bar off to one side and one dining room beyond a narrow exposition kitchen fronted by an eating bar. The second dining area was in the attic upstairs, under the pitched roof. The walls were of a stark white decorated with clusters of vintage photographs in gilt frames. There were portraits of stern-looking women in monstrously large hats and posters of passengers waiting to board a Mississippi River paddle boat. “Dixieland” was emblazoned across one image over our table.

The food and drink were very good. Chef/owner Charlie McKenna is best known in Chicago for his reliable barbecue restaurant, Lillie’s Q. But this South Carolina native is a Culinary Institute of America grad and a veteran of Norman Van Aken’s Florida flagship, Norman’s. He has finer dining in his bones, and you can sense his eagerness to return to this world at Dixie.

I would be happy any day eating McKenna’s salad of chilled cucumber ribbons with pickled onion and benne seed wafers in a buttermilk dressing, then moving on to his succotash with crunchy-sweet fresh corn, seared okra, and edamame with a juicy, harissa-spiced catfish fillet. This is smart Southern cooking, and if the edamame sounds strange, consider he already had to get a local farmer to grow his okra. “We should have field peas next year,” he promises.

Beverage Director Dylan Melvin has assembled an incredible selection of old and rare bourbons. His cocktails, which come in vintage cut-glass coupes, taste complex and balanced—old-school flavors with a modern edge. The Southern Whiskey Sour sports a subtle red wine froth, while a drink called The Greenwood offers a weirdly satisfying herbal rush of Oude Genever with pear bitters. These drinks evoke a sultry, complicated place. Two plates and two cocktails would put me back $75, and I’d need to end the evening with a bowl of cereal at home, but it would be worth it. I have a feeling this scenario will play out often.

McKenna hand-delivers our dessert, a really great take on chocolate chess pie served with a sorghum vinegar caramel and sorghum marshmallow sauce. He says he’s pleased with the pristine white walls and clean lines of the decor. “It feels like the South, right?” he asks eagerly.

Kinda, maybe, sorta? It certainly feels like an aesthetic vision of the South, one that’s steeped in history but not conflict, one that imagines a perfect continuum into a modern world where farmers grow your butterbeans in Illinois and grandma’s cocktail glasses have been handed down to the Fernet Branca generation. In a way, it’s the perfect restaurant for this augmented-reality world of Pokémon Go. It’s our reality overlaid by a better one, sprightly and animated, a place of both cognitive dissonance and real charm.

John Kessler was the longtime restaurant critic for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He is currently working on a book with The Giving Kitchen, an Atlanta nonprofit.

John Kessler was the longtime restaurant critic for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He is currently working on a book with The Giving Kitchen, an Atlanta nonprofit.