In Gravy issue #54, the SFA interviewed Dr. Charles Reagan Wilson on Southern food and pop culture. We learned a lot from that interview, including this important note about pop culture: it is not so much concerned with authenticity as it is with reproducing traditional symbols for broad audiences. In other words, your tacky souvenir collection from Stuckey’s is both about the South, because it was likely gathered there, and yet not about the South, because—really—how many people do you know who have alligator ashtrays in their homes?

Issue #54 was a unique issue, as it showcased more art and photography than written text. In addition to Dr. Wilson, we would like to thank all the contributors, photographers and artists alike: Cedric Smith, Emily Wallace, Earl Simmons, the Attic Gallery, Kate Medley, and Denny Culbert.

Southern Food and Pop Culture

Southern Food and Pop Culture

Connecting tradition and modernity

Charles Reagan Wilson holds forth

Southern Food and Pop Culture

Connecting Tradition and Modernity

As told to Sara Camp Arnold by Charles Reagan Wilson, November 21, 2014

***

DEFINITIONS & HOGS

Popular culture is mass culture. It’s mass-produced. It doesn’t strive for authenticity, for craftsmanship, so much as to promote consumption. It is made for wide audiences, not for narrow audiences. You can make an easy contrast with folklife and folk culture, which tends to be rooted in communities and built around social groups.

In the South, pop culture is negotiated between tradition and modernity. It often draws from folklore, from folk symbols and rituals. But it is not so much concerned with authenticity as it is with reproducing these symbols for broad audiences.

One of my favorite examples of this negotiation is the pig. Hogs were a major source of Southern foodways going all the way back to settlement. When the South produced what we might call a fast food place, the barbecue joint, the pig was at the center of it. Barbecue restaurants seem traditional. But they also commodify a traditional Southern food. The pig itself becomes the negotiator, the popular culture symbol that draws together tradition and modernity.

That’s one point: Popular culture is mass-produced. It connects tradition and modernity, and produced a group of common, well-known symbols and icons that become associated with the South itself.

AUNT JEMIMA & JEB STUART

The New South movement in the 1880s was about diversifying the economy and making the South wealthier. In that period of the late nineteenth century that, the South produced popular culture representations and artifacts related to the Lost Cause and to the Confederacy. Robert E. Lee on a bag of flour, for example. His image had moral authority in the South. You had Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis. You had Jeb Stuart, the romantic cavalryman. He was very sale-able. So you had those images on plates, on all sorts of mass-produced goods.

Often those goods were manufactured in other parts of the country. Despite the New South movement call for economic diversification, the South remained a largely agricultural area. In the American industrial economy, the North was often the producer, and the South that was the consumer. Mass-produced popular culture items were symbols that the region’s people could respond to. Southern advisers often served Northern companies that sold goods in the South.

Aunt Jemima is a good example of this. Aunt Jemima was introduced at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Nancy Green, a freed slave, was the original image for the first ready-mix pancake mix. What Aunt Jemima sold was the South as a place of gentility and servants. Popular culture is about mass-producing images, but also mass-producing pancakes.

What Aunt Jemima gave the company was this image, deep in the American psyche, of the South as a land where people served you. Even though it’s fast and convenient—you’re giving kind of a moral authority of the culture from the South—it’s like she is symbolically serving you. She always is portrayed with the bandana, the apron. When she appears in person, like at the World’s Fair, she speaks in dialect. She tells tales about the Old South. This is part of this romanticization of the Old South that occurs in the late nineteenth century. The company that produces Aunt Jemima is not from the South. It is a Northern company exploiting this fascination with the South in the American market.

GOOD TO THE LAST DROP

In the 1920s and 1930s, popular culture forms that were not distinctive to the South, but made use of Southern materials, emerged, namely movies, radio, and phonographs. In the 1930s, marketers of food products—Maxwell House coffee is a good example— were sponsoring radio shows. They had a live radio show from Nashville. There was an actual Maxwell House hotel in Nashville, and that’s where the brand name comes from. Here’s this fancy, upscale Nashville hotel. Of course, they have black waiters who are serving the coffee. of the Maxwell House image on radio and in their advertising. And so it’s the ideal of this gentility, of morning coffee, with a waiter serving you—all of this becomes a popular culture way of selling coffee.

Part of what popular culture does is take these experiences of Southern culture and projects them onto the national scale. So they become American as well as Southern.

COOKING WITH ELVIS

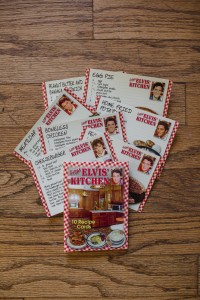

Gravy: You have this set of Elvis recipe cards. And Elvis is not someone I associate with food, except a peanut butter-and-banana sandwich.

You can’t say Elvis was a gourmet. But Elvis loved food. And he would have had to be a member of the Southern Foodways Alliance if he was still alive. But these recipes—they’re not very imaginative, you know. A hamburger, boneless chicken, meatloaf, home-fried potatoes, and a ham sandwich.

Gravy: Why would a marketer want to connect Elvis and food?

Because you connect Elvis to everything. There’s a market for Elvis. Because people who are crazy about Elvis are crazy about all things Elvis.

I think Elvis’s audience today is Southern whites, it’s working-class people, and it’s women. All of those people are touched by Elvis. Despite his extraordinary celebrity and success, he remained very much an identifiable white Southerner of a certain time period and place. And his food was part of that. A lot of working-class white Southerners identify with his food.

We say in the South, “You don’t get above your raising.” And Elvis never got above his raising. And food was a classic case of how he never got above his raising. He was not aspiring to go to a high-style restaurant or eat fine food. He was eating what he grew up eating, and he still loved it all his life, even though he could go anywhere and he could afford to eat anything. And I think people who would buy these cards appreciate that about Elvis. And they probably are going home and cooking these recipes.

CHITLIN STRUT

One of the things we haven’t talked about in terms of popular culture is festivals. Most of the festivals in the South today are popular culture, but they grew out of folk traditions. The fair, the county fair, is the folk progenitor. At the county fair, in the old days, you would have had a beauty contest. You would have had the queen of the county fair. Out of that came the beauty pageant that is popular culture. They’re not the old folk festival that goes back to agricultural fairs. They’re modern. They commodifying the women in terms of the beauty pageant.

So many of the festivals today are popular culture in that they aim at a mass audience. And they are often all about consumption. But they still draw from that traditional Southern iconography. In Mississippi, the watermelon festival in Water Valley is an example. So is the catfish festival in Belzoni. There’s a chitlin strut in Salley, South Carolina, which I love. I’ve never been to it; that’s one of the places I’d love to go. Even something lowly like chitlins, they have raised it up, and it becomes a tourist attraction.

LUCKY DOGS

Places have their particularities. In the postmodern twenty-first century, tourism is everywhere. We’re trying to get people to come to our places, to spend their money, and food—it has to have some relevance in a local place. And so New Orleans is the classic case: eating oysters at Acme Oyster bar, buying the beignets from Café du Monde, and getting the muffuletta at the Central Grocery.

My wife’s family made homemade Italian sausage. They lived in Jackson, Mississippi. And when my wife was a little girl, they would drive to New Orleans to go to Central Grocery to buy the fennel seeds that you couldn’t buy in Mississippi. They were an “Italian food” ingredient. Central Grocery was owned by an Italian family. Her family would drive down from Jackson to New Orleans, they’d eat a muffaletta, they’d drive back, and make their Italian sausage. They made a special trip—tourism—to get this fennel seed for their Italian sausage. That was a long time ago. But that’s an example of a way that food can figure into people coming to a place and spending their money, which is what the tourist industry wants them to do.

It goes back a long way, but Lafcadio Hearn, in the late nineteenth century, wrote some of the earliest articles about food in New Orleans. He talks about the street vendors. And they’re still there. Lucky Dogs: that’s a good example. In New Orleans, food is central to your experience. Whether it’s eating at a world-renowned restaurant, or a beignet, or a muffaletta. Or, as the bars are winding down, eating a Lucky Dog.

SOMBREROS & TACOS

The demographics of the South have changed fairly rapidly in historical terms. Most notably you now have Mexican restaurants in huge scale. The imagery of Mexican restaurants is often stereotypical: sombreros and donkeys. That’s becoming a part of the Southern iconography.

These restaurants have become a part of the collective popular culture landscape. I’m a big believer in landscapes. The landscape of the South has evolved to incorporate Mexican food. You see it whenever you eat in a Mexican restaurant. It’s not just Latinos eating there. A wide range of whites and blacks and Asians and whoever else wants Mexican food. For all of these people, Mexican restaurants are part of a specifically Southern landscape, where you have the choice of getting fried chicken or barbecue or hamburgers or tacos.

***

Popular culture provides easily accessible representations of the South. They’re mass produced, and they’re easy to dismiss. They often have a sense of humor about themselves, and that’s one thing I like about them. They’re kitsch: the Stone Mountain paperweight. And they often offer lively commentary through their imagery or design features. And they can tell us something about the South.