(Francisco Oscar Miranda. Courtesy of Cigar City Magazine.)

The history of the devil crab and the Tampa cigar industry are inextricable. Once made with a then plentiful but now depleted supply of blue crabs from Tampa Bay, the story of this fried street food is deeply rooted in labor and immigration1.

When Vicente Martinez Ybor, a major cigar magnate originally from Spain, brought the cigar industry to Tampa from Key West in 1885, he created a “boomtown atmosphere.”2

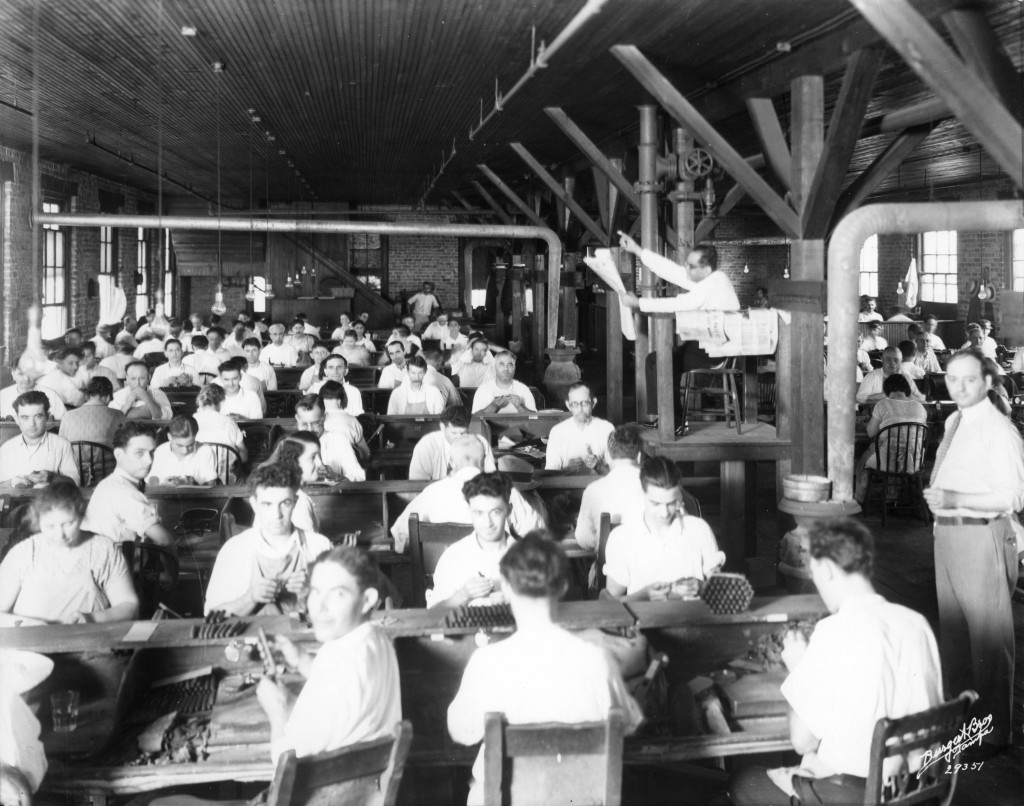

By 1910, there were more than 150 factories in Tampa, predominately in Ybor City (incorporated into Tampa in 1887). This humid, port city attracted workers from Italy, Cuba, and Spain, and various parts of the Caribbean. “The history of Tampa after the settlement of Ybor City,” writes historian Gary Mormino, “is largely a chronicle of a southern city struggling with the dynamic changes that an expanding industry and a diverse immigrant work force introduced.”3

Many point to Ybor City and a cigar factory strike in 1920 as the devil crab’s origin. Others suggest devil crabs were brought to Tampa as a Spanish croquette and assimilated by the rich Sicilian, Spanish, and Cuban communities of Cigar City. Some have even linked them to the Key West conch fritter or the creamy, Chesapeake Bay crab cake. Whatever their roots, “Ybor City foodstuffs were always a blend of Old World dietary customs filtered through emigration, Americanization, and prosperity-poverty.”4

Devil crabs, or as some like to say deviled crabs (because they are “hot as the devil”) are made from crab meat, fried green peppers, onion, garlic (known as sofrito), tomato sauce (much like what’s known in the Cuban tradition as enchilau), red pepper flakes and other spices. Which other spices depend on the maker. The mixture is formed into balls and traditionally rolled in crumbs made from day-old Cuban bread, and then fried. In lard.

Devil crabs were made at home but were most popular with street vendors like Francisco Oscar Miranda, the man in the portrait above, and Cesar Beiro. Vendors roamed the streets of Ybor City on foot pushing carts and motorized scooters hollering “jaibita caliente!” and “hot devil crab!”5 They were sold for a nickel.

Long gone are vendors like Miranda and Beiro as is the bustle of early twentieth century Ybor City. But the devil crab remains popular in markets and stores in West Tampa, from restaurants in Ybor City like the Columbia, Carmine’s and La Tropicana Cafe, to the palmetto leaf-topped loaves of bread baking in La Segunda bakery, to food trucks, to the women fastidiously rolling the filling into strict dimensions at Seabreeze Restaurant. The crabs are no longer from Tampa Bay. The croquette’s size grows, probably to entice tourists. Still, the rich diversity of the Tampa devil crab continues to hold fast to its Italian, Cuban, and Spanish roots.

[1] Edge, John T. “In Tampa, the Street Food that Crawled from the Sea,” New York Times, April 26, 2011.

[2] Hewitt, Nancy A. Southern Discomfort: Women’s Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s-1920s. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001, 44.

[3] Mormino, Gary and Pozzetta, George. The Immigrant World of Ybor City: Italians and Their Latino Neighbors in Tampa, 1885-1985. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1987, 44.

[4] Mormino, Gary. “Casablanca in Ybor City,” Tampa Tribune, March 11, 2007.

[5] Houck, Jeff. “Delicious: A tasting tour of Tampa’s native devil crab croquettes reveals scrumptious variety,” Tampa Tribune, February 9, 2011.