This story first appeared in the winter 2015-16 issue of our Gravy quarterly. The author, Alice Randall, presented a version of this piece at the 2015 Southern Foodways Symposium.

Join or renew your SFA membership to receive a subscription to Gravy in print. Thanks to SFA members, whose support helps make Gravy possible.

Glori-fried and Glori-fied

Mahalia Jackson’s Chicken

by Alice Randall

Imagine yourself for a moment in a pew in a South Side Chicago church, in 1965, or 1966, or 1967, with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the lectern—serious, head down, staring at his notes. A choir sings, one voice rising above the others. Dr. King turns away from the congregation toward the voice and smiles, the sweetest smile, a smile of true joy, as the voice sings a battle cry: “Joshua fit the Battle of Jericho, Jericho, Jericho, Joshua fit the Battle of Jericho and the walls came tumbling down.”

The men and women in the pews begin to clap and sing even louder as they are gathered into an army, not by Dr. King in the pulpit, but by the woman leading the choir, a beautiful woman, large and brown, in a crisp silk suit with giant buttons. When the song comes to its end, when the crowd finishes thundering its readiness to fight, led by this singer and this preacher, Dr. King says, “I think I can say, concerning this great gospel singer in our midst, our dear friend, my great friend Mahalia Jackson, that a voice like this comes only once in a millennium.”

Mahalia Jackson was an international star, a principled artist who refused to sing music that was not gospel. A passionately political woman, she could wrestle attention from Dr. King, even while giving him pleasure and respite. Why would she choose to lend her name to a fried chicken franchise?

I have given a lot of thought to this question in the last few years.

I knew that my first husband’s godfather, a black man named DeBerry McKissack, had designed the iconic buildings that housed Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken. I knew that John Jay Hooker, a prominent white lawyer, entrepreneur, and friend of Muhammad Ali’s, had backed both Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken and Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken. I knew that both businesses had failed. I sensed that country comedian Minnie Pearl’s was fundamentally wrong and Mahalia Jackson’s was somehow fundamentally right, even if they shared the same or similar recipes for fried chicken. I couldn’t tell you why.

Glori-fried or glorified? Is there more to the franchise than yardbird, salt, pepper, and grease? Does the business exploit the Queen of Gospel’s associations with the sacred, or is her involvement with the chicken enterprise a kind of savory and secular beatification?

I was born in Detroit in 1959. I remember my family waiting and wanting a Mahalia Jackson’s to open in Motown. I had a vague impression that Mahalia Jackson’s was important to black America in the 1960s. But I couldn’t tease out just why.

I was overeager to find the original recipe for the chicken, hoping there was some magic in the formula that would prove Mahalia’s genius, hoping there was something in the taste of the chicken equal to the sound of her voice. There wasn’t.

I have spoken with many, many folks who ate the chicken, loved the chicken, adored the chicken. None of them thought it tasted more than good enough. What they loved was the idea of Mahalia and chicken.

Born Mahala Jackson on Water Street in uptown New Orleans in 1911, the future greatest gospel singer of all time began singing at Plymouth Rock Baptist Church and Mount Moriah Baptist Church. Since the mid-1950s, the New Orleans neighborhood where she lived has been called Black Pearl. Back when she was born, it was simply called “Niggertown.”

Mahala moved to Chicago in 1927, joining a church choir almost immediately. She renamed herself Mahalia in honor of her beloved aunt. Four years later, in 1931, she recorded her first song, “You Better Run, Run, Run.” It would be nearly 20 years before she had a smash hit. In 1947, Mahalia Jackson recorded “Move On Up a Little Higher.” It sold over 8 million copies.

Those 8 million copies sold meant that Mahalia Jackson impacted the South’s understanding of itself, and she helped frame the North’s understanding of the South. Eight million copies sold meant that some 80 million people likely heard the song. Mahalia Jackson was the first, and arguably the most significant, black female superstar of the 20th century.

Harry Belafonte declared her the “single most powerful black woman in the United States.” He believed there was not “a single field hand, a single black worker who did not respond to her civil rights message.”

“Move On Up a Little Higher” is a song that seems a simple promise about going to heaven. It is so much more.

When Mahalia Jackson first stepped into the national spotlight, she made a prediction about food. “I’m going to feast with the Rose of Sharon,” she sang, declaring herself a black woman fit to eat with whites. She claimed an integrated table. She raised her voice like a mighty sword, singing, “Monday morning, soon one morning, I’m going to lay down my cross, get me a crown…. Soon as my feet strike Zion, lay down my heavy burden.”

What was the cross that millions of women, mainly black women, understood Mahalia to be putting down at the end of a long Monday? Could it have been a cast-iron frying pan? Could it have been a maid’s apron? In young Mahala’s experience, where did black women like her mother and aunt go on Monday morning? To work in a white woman’s kitchen and house. Mopping and washing and frying chicken. And that’s where Jackson eventually went.

Before she moved to Chicago, Jackson worked as a domestic servant in New Orleans. To feel the weight of that statement, remember: she was only 15 or 16 years old when she left the South for the North. Her first appearance in the white world was in a maid’s uniform. She left school in the eighth grade to work as a cook and washerwoman. When she arrived in Chicago, she took jobs as a hotel maid, a laundress, and a babysitter.

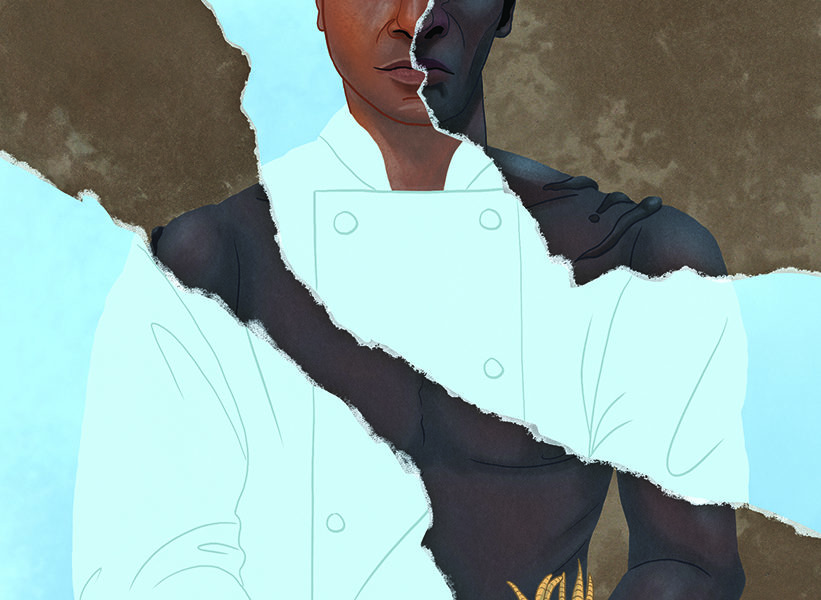

By lending her name and her image to the fried chicken enterprise, Jackson was trying to put a choir robe over a maid’s uniform before stripping them both off in favor of a knit business suit. She entered into respectability through the shaming kitchen door, kicking the door down as she stepped.

Jackson ventured into the kitchen to be far more than respectable: She used respectability to introduce radicalism. And like Floyd McKissick’s Soul City in North Carolina, Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken empire was a fabulous failure. But before it failed, it enjoyed some very significant successes. Mahalia Jackson sought to use franchise food as a kind of Trojan horse to introduce economic vitality into the belly of black communities.

There was a bit of Marxism in her recipe. A bit of black Muslim self-reliance. And a whiff of gasoline. Here’s what Gulf Oil had to say about the audacious plan:

“We are pleased to be associated with Miss Jackson, a respected and renowned personality, and her company. Since Mahalia Jackson’s Chicken System is black-owned, managed and staffed and is hiring in the communities in which it operates, Gulf hopes it is helping to provide blacks business and employment opportunities.”

Beyond jobs and wages, Mahalia Jackson’s offered employees paid vacations, low-cost life insurance, and major medical benefits. The System grew to include a management school.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken opened in cities across the country. In her adopted hometown of Chicago, there were, at one time, five Mahalia Jackson’s.

Mahalia moved on up from poverty-stricken New Orleans to European and Asian concert halls. Her face on the chicken bucket said, this chicken is fancy, this chicken is fine. The chicken gave pride back to black folk, just the way her music gave pride back to black folk on the hardest days that came.

In the black world, Mahalia Jackson’s chicken enterprise is a culinary Camelot. A shining, vanished moment. A place where black people did the cooking and the eating, the sowing and the reaping. A place where blacks were the owners, managers, workers, and patrons. Such a place existed for a moment.

And this is what it looked like; this is how my godfather DeBerry McKissack designed it, according to New York’s illustrious black newspaper, the Amsterdam News, “The white brick, carry-out chicken stores look like highly styled, modern churches with their red roofs climbing to high pointed peaks. Flying buttress wings, carrying signs shaped in the elongated oval of cathedral windows flank the stores on either side.”

Despite the fact that Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken System lost money, Mahalia Jackson died a rich woman, leaving an estate of approximately four million dollars to various relatives. She didn’t go into the chicken business only to make money. She went into the chicken business to help others make money, and quite possibly to redeem kitchen work, to transform it from a private hell into a public and pride-filled business defined by stock and dividends rather than slaps, insults, toting privileges, and rape.

Mahalia Jackson understood the power of food. She claimed as her greatest pleasure and entertainment feeding people in her home. She knew food to be a personal pleasure, a spiritual necessity, and a political statement.

Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken restaurants were embedded in the black communities they served. Due to a perfect storm of white redlining, poverty, Negro removal-slash-urban renewal destruction, and rising rates of drug addiction and unemployment, some of these neighborhoods were areas of concentrated crime. Mahalia Jackson franchise locations were often the sites and victims of robberies.

The very first Mahalia Jackson Fried Chicken franchise opened in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968, just months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. My own godmother, Leatrice McKissack, wife of the architect, was robbed there the day it opened. She entered the restaurant looking sharp, a twin daughter holding each hand. A purse with credit cards and cash swinging from the crook of her arm. After the official opening, she reached into her purse and discovered her wallet was gone. Ben Hooks and A.W. Willis, lawyers and activists who founded the flagship, called and cancelled the credit cards for her.

Today her daughters, Cheryl McKissack and Deryl McKissack, the twins who toddled into the opening of the first Mahalia Jackson’s in Memphis, are the owners of two of the oldest and largest black-owned architectural and engineering firms in the world. Between the two of them they have offices in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, Nashville, New York, Miami, and Washington, D.C. I like to think they developed a taste for franchise standing in Mahalia Jackson’s nibbling on a fried chicken wing, listening to all the talk about black nation-building through black wealth-building.

Psyche Williams-Forson has written ably of building houses out of chicken legs. My god-sisters have built skyscrapers, national monuments, movie studio buildings, and roads inspired by Mahalia Jackson’s chicken.

Respect, economic self-reliance, risk-taking, mutual aid: These were the secret ingredients in Mahalia Jackson’s recipe. At the end of the day, the day that ends in Zion, the chicken was glori-fried and glorified.