CORN: THE ETERNAL MEXICAN A field guide to snacking

by Gustavo Arellano, with illustrations by Haejin Park (Gravy, Summer 2016)

Corn was the original Mexican migrant to the South.

At some point millennia ago, maize took a miraculous journey from its birthplace in the southern Mexican highlands (where the ancients domesticated it from its wild ancestor, teosinte) through the mountains and deserts to the modern-day Southwest. From there, corn made its way to the South. The Cherokee Nation says it has harvested corn since 1,000 B.C.E., and each tribe tells an origin story of how corn came to them. Almost universally, those narratives center on a supernatural spirit or god who gave people the crop as a gift. Giving and receiving so that everyone benefits: That’s immigration at its best.

Corn still possesses that power to tell the story of a people. Even when rendered as snacks. Especially when eaten as snacks. Documenting the corn snacks that Mexicans in the South consume is like an making an edible map of the region’s varied Mexican populations. Traveling the South in recent years, I’ve catalogued and enjoyed a wide range of corn-based antojitos. I see more and more popping up every año. If you want to follow my trail of tortilla chips, start here.

ATOLE AND CHAMPURRADO

These primordial hot drinks are weekend staples of Mexican eateries across el Sur. Much like moonshine and whiskey, save the alcohol, atole and champurrado are mother and daughter. Atole is made by boiling masa down with water, tossing in cinnamon, piloncillo (unrefined brown sugar), and vanilla to taste. Champurrado adds chocolate, preferably Ibarra over Nestlé Abuelita. Both achieve the same result: piping-hot and comforting, sweet and savory, the best weapon against the cold outside of a tiger-emblazoned blanket, which every Mexican household in the Southwest owns for both warmth and kitsch value. Are those in the South yet?

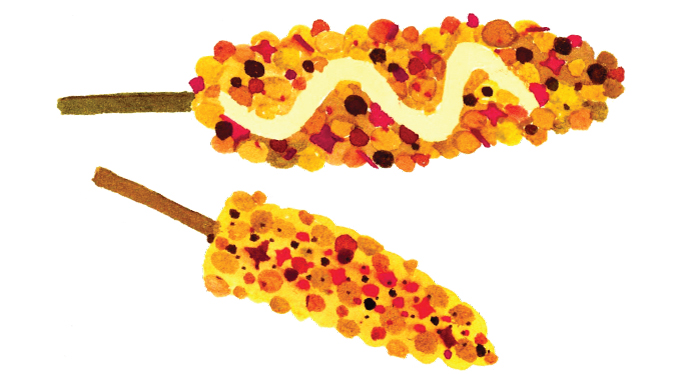

ELOTES

Southerners eat corn on the cob; we have elotes. Eloteros—literally, “corn men”—roam barrios across the country, pushing carts laden with grilled and steamed ears, which they slather with mayo, chile powder, butter, and lemon. Pardon the cultural superiority, but no one knows how to prepare corn on the cob the way we do: The results are luscious, filling, messy, beautiful. Eloteros hail their presence with bicycle horns (if you hear bells, that’s going to be the Mexican ice cream man—a lesson for another column). Spanish tip: Say “¿Me da un picadiente, por favor?” when you realize you need a toothpick.

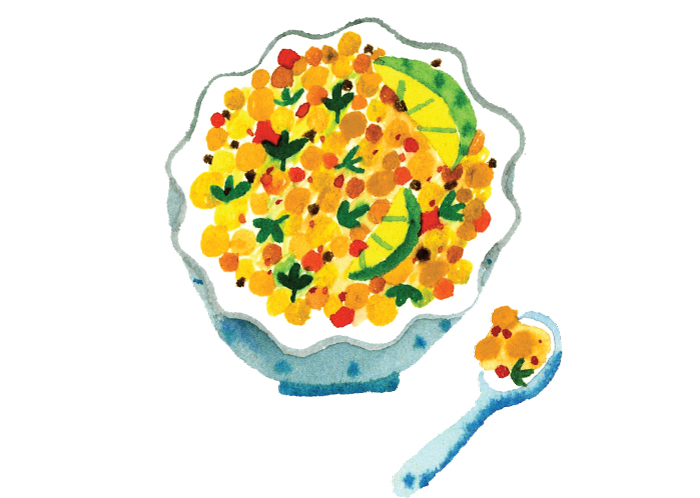

ESQUITES

Related to elotes are esquites, a corn-based dish that’s virtually unchanged since the time of the Aztecs. Served in a cup instead of on the cob, it’s made with roasted kernels, onions, butter, and epazote (a Mexican herb as renowned for its pungent taste as its powers to reduce flatulence—I’m here all week, folks). Good esquites are notoriously difficult to make. Make them poorly, and you have mush; make them perfectly, and each kernel is a juicy jewel floating in a buttery broth. The trick is to roast the kernels long enough so that they’re almost pebbly. They will plump in the broth and retain a slight crunch. Given many Mexican immigrants to the South come from Mexico’s southern states, whereas esquites are mostly a central Mexican delicacy, feel blessed if you find them near you.

TAMALES

While Delta-style tamales have enlivened the Southern diet since the late 1800s, Mexican migration is so persistent that regional tamale variations are now available north of the border. Tamales wrapped in banana leaves telegraph a southern Mexican provenance; the best of those are tamales de mole negro, featuring chicken and a chocolate-based mole. Corundas are inside-out tamales: triangles of masa topped with strands of chicken or pork and sour cream. My favorites are uchepos, tiny dessert tamales made of tender sweet corn and milk that hail from the central Mexican state of Michoacán. I’ve only eaten these special tamales at house parties. Another reason to befriend the Mexicans in your town.

TEJUINO

If you find this agua fresca, congrats: You have in your midst people from Colima or Jalisco, birthplace of tequila and mariachi. Tejuino starts as an atole. Cooks let the drink ferment, cut the results with piloncillo and salt, then serve it chilled with a scoop of lime ice cream. Ever tasted kombucha? It’s like that, except better: funky, tangy, irresistibly sweet. Jaliscan food has become trendy among Mexican Americans in the past couple of years, so look for tejuino in fancier Mexican restaurants or forward-looking bars.

TAKIS

Mexicans love their antojitos. The more processed, the better. Takis are essentially the mestizo child of Fritos and Cheetos, but with more spice, tang, and bite. These should definitely be at your local mercado, neighborhood convenience store, or Piggly Wiggly. If not, do yourself a favor and demand them.

Each of these snacks is built on a base of masa.

By treating raw corn kernels in an alkaline solution, Mexican cooks simultaneously leeched off the toxins while adding nutrients like niacin. That’s why we ate a corn-based diet but didn’t suffer from the pellagra that historically plagued the U.S. South. Speaking of masa, stay away from the dried stuff called masa harina. It produces tortillas that taste like dust. Instead, look for tortillerías that grind their own masa, often from local corn. Tortillería y Taquería Ramirez in Lexington, Kentucky, for instance, gets its corn from the Bluegrass State’s famous Weisenburger Mill, resulting in hefty tortillas that taste and smell earthy and don’t tear easily—as bueno as any I’ve eaten in California.

Gustavo Arellano is editor of OC Weekly in Orange County, California, and author of Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. For every issue of Gravy, Arellano writes a “Good Ol’ Chico” column.

Gustavo Arellano is editor of OC Weekly in Orange County, California, and author of Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. For every issue of Gravy, Arellano writes a “Good Ol’ Chico” column.