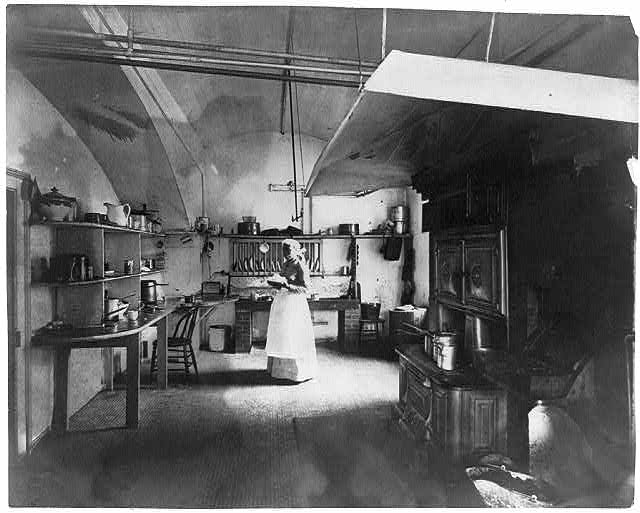

Back of the White House Researching the history of US presidents’ kitchens

as told to Gravy by Adrian Miller

Recently, UNC press published Adrian Miller’s The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas. An SFA member and the James Beard Award–winning author of Soul Food, Miller aimed to fill in the “historical silhouettes” of the black culinary figures whose influence he noted while researching his first book. For Miller, this book is about righting the record. While the circumstances, names, and personal contributions of these men and women often passed without attention, Miller argues that these African Americans were culinary artists whose recognition is long overdue. “Many were also family confidants,” he told Gravy. “In some cases, they were civil rights advocates. Some were all three.”

How did you compile research for this project?

This started when I was doing the Soul Food book research. I found stray references about African Americans who cooked for our presidents in newspaper articles. Then I gathered all of the

cookbooks that were either written by White House cooks or by third parties as a summary of White House cooking, because I wanted to see references made to African Americans. Then I looked at presidential memoirs and biographies to see who was mentioned. They just jumped off the page.

I visited eight presidential libraries. It’s hit or miss in terms of what the libraries have on food. If the archival team and the White House photographer weren’t interested in the food or the kitchen, then there’s very little. But you had some that were interested and detailed. At the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, if you pick a day when Carter was in the White House, you can pretty much get the menu of what he ate in the residence. Most of the time, we only get menus for the state dinners. But they didn’t start printing or saving them until the Eisenhower administration.

The last part was personal interviews with presidential cooks who were willing to talk to me. I reached out to several. I tracked down ten former White House chefs: four African American, six white. Of the four African Americans, none would talk to me. And of the white chefs, five out of the six, not only did they talk to me, they’re telling me stuff that I shouldn’t even hear. That is interesting because they all signed the same paperwork. The white chefs felt more liberated to talk than the black chefs. I think understandably the black chefs were like, “There’s probably more professional repercussions for us if we’re seen as talking out of school.”

Going into the nineteenth century, many kitchen staffers weren’t referred to by name, or by their full name. How did this impact your ability to identify people?

Once I got a stray reference about a cook, I became obsessed with trying to find out as much as I could. The primary resource here was historic newspapers. The Library of Congress and several private companies have digitized old newspapers, and they’re word-searchable. But if I couldn’t find anything through newspapers or through Google Books, I figured it was just going to be a needle in a haystack.

For each chapter, I created categories of presidential cooks, then tried to find three to four people whom I could find enough detail about to anchor that chapter. There’s a lot of information about cooks in the founding fathers age up to Jefferson. Washington and Jefferson compiled a ton of information about their cooks and then it’s pretty bone dry. But I knew that once I got past the 1890s, there’d be more. From the 1890s to the 1980s, there’s a lot of information.

By categories of presidential cooks, you mean all staffers who were involved with food preparation.

Yes. I didn’t just deal with cooks in the basement kitchen. I tried to take a look at the constellation of cooks who supported and fed our First Families. That helped with the research gaps, because then I could include people that cooked on trains, yachts, and other places.

Do you see a correlation between the influence of a president and what we know about their household foodways?

There definitely is something about celebrity status. People were more curious about what was going in their household and there are more references to it. But the interesting thing is, there’s not a lot of information about the food they ate while they were president. I thought that all these people who had dinner with them, everybody would write about it in their diaries. I didn’t see much, and I was a surprised by that.

Is this related to our increased interest in food reporting over the years?

I think that our presidents were self-conscious about not giving fodder to their political enemies to criticize them. Food was one of the tools that people used. Washington was self-conscious about appearing like a monarch.

You’re saying politicians were concerned with how their food tastes could be used against them.

Right. The poster child for all of this is Martin Van Buren. His political enemies painted him as an out-of-touch elitist by talking about how he ate with golden utensils. That narrative stuck, and he actually lost reelection.

That barb has persisted—the out-of-touch elitist—arugula, and what not.

Exactly right. Food is often a leading indicator of having an elitist attitude. One more thing that was annoying for me, just to show you how differently we view food now compared to the past: Even with the state dinners, which are these grand entertainments, I’d find elaborate, intricate descriptions of the table settings, the flowers, everything. Then they’d say, “And there was a grand meal held.”

What terms did you search under?

I’d look for “White House” or “president’s house”—they didn’t start calling it the White House until later in the 1800s. Also “meal,” “dinner,” “state dinner,” “grand entertainment,” and “bill of fare”—people didn’t really say menu. Those terms generated a lot of menu and dinner descriptions. For the cooks, I’d search “White House,” “colored cook” or “Negro cook,” and sometimes I’d do “nigger cook” just to see if it came up. Even in The New York Times they would use that term, but it didn’t show up as much. It was mostly Negro or colored cook, and Negro or colored caterer. I didn’t find “Negro chef” or “colored chef.” It was “cook.”

Let’s talk about a few specific figures. Laura “Dollie” Johnson cooks for Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Then she capitalizes on her time in the White House and opens a restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky, afterward. What impressed you about her?

Dollie Johnson-Courtesy Library of Congress

She’s one of the most fascinating people I’ve come across in my research. She is somebody who has to be persuaded to work at the White House. Before her time, most African American White House cooks were either enslaved or already a longtime cook for somebody who happened to become president. Here’s this woman who wants to start a business, and presidential staff is pleading with her to come cook for them. It shows me the leverage and bargaining power she had. She cooked for Harrison but only stayed for several months because her daughter got sick, so she returned to Lexington. But when Cleveland gets elected, he begs her to come work for him.

I’ve been trying to figure out why she was so distinctive. There were others who were similarly situated who did not get the national headlines that she got. Maybe it was because Theodore Roosevelt was a booster of hers, and he recommends Dollie Johnson to Harrison.

Let’s talk about Daisy Bonner, who cooked for Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his estate in Warm Springs, Georgia.

I found several different strands of the story about Daisy Bonner. I get alerted to her through newspaper clippings. I went to Warm Springs and listened to the park ranger’s stories. In the book Hi-Ya Neighbor, which is about FDR’s time in Warm Springs, Bonner is all over that book. That’s what really catapulted her story for me. There are pictures of her; it talks about several of the dishes she cooked for FDR, and how they interacted.

The thing that hit me hard was going through Warm Springs on the tour. I was in the kitchen where she cooked and heard the story of how at FDR’s passing, she wrote on the wall that she cooked the first and last meal for the president. I went into the cottage that she lived in on the grounds. Unlike other people I write about in the book, I was able to have a physical attachment to Daisy. I could go to the workspace where she worked and the place she stayed when she cooked there. For a lot of these other people, where they worked, where they stayed, all of that has been demolished.

Describe country captain, a local specialty she cooks for FDR.

It’s a chicken curry dish. The story, likely apocryphal, is that a ship from the West Indies was carrying spices and was forced to dock in Savannah due to a storm. A local cook uses the spices to create this curry dish. It’s a Georgia thing: chicken with a curry sauce, and you add condiments like toasted coconut, peanuts, raisins, or currants.

Bonner gets FDR hooked on pigs’ feet.

FDR loved her pigs’ feet. When she made pigs’ feet for him, she would broil them and butter them. And she made a pecan cake that he really liked. Then of course there’s the cheese soufflé, which supposedly stood for two hours after he died. I don’t know how that happened, because I made that recipe and the thing falls immediately.

Zephyr Wright is a key figure. She travels with Lyndon Johnson and his family, but stops because of the indignities she faces due to segregation. Their relationship influences his lobbying Congress to support the Civil Rights Act. What about her story was new for you?

When you read interviews with her, she seems to be, as she recounts it, nonplussed about the civil rights movement. She wasn’t really a firebrand. LBJ would often ask her, “What do black people think about what I’m doing? Do they appreciate what I’m doing?” And she would give these answers that would infuriate him. She’d say, “I guess,” or “I don’t know.” I’m not sure if she’s messing with him or what. These exchanges were surprising to me. Because what I’d fancied were these deep moments where she’s counseling him, where she’s the inspirational force for him to act. But it seems like it was more by her example rather than her actively pressing him.

I do love the story of LBJ using Zephyr Wright’s Jim Crow experiences. Not only did he do this with members of Congress, he started doing this with the elites in Georgetown. He knew that it was an inside/outside game. If he could use her story to change the hearts and minds of the academics and the wealthy people in Georgetown, that could help him get leverage and influence members of Congress.

Wright and Johnson had a unique rapport, it seems.

You hear stories about LBJ; he was not a shrinking violet. But Zephyr Wright gave it right back. He’d show up at 9 p.m. at night demanding dinner and she’d yell, “You just go sit in the kitchen and wait.” And he’d do it!

Is that indicative of real power Wright held, or is that akin to the mammy role—in that during this period white people with black, domestic employees tolerated a certain amount of attitude from black women? How do we read an exchange like that?

I think it’s a mix—it’s certainly part of the latter. But she was one of the few people who could talk back to him. A story that LBJ loved was that at the height of the Vietnam War, one of his strongest critics was Senator William Fulbright. Fulbright said in the press that LBJ had an arrogance of power. LBJ cornered him at a cocktail reception and pulled a handwritten note out of his pocket from Zephyr Wright. I’m paraphrasing, but it said, “Mr. President, you don’t seem to want to take care of yourself. I’m gonna be your boss. So from now on you’re going to eat whatever I put in front of you, and you’re not going to complain.” LBJ would say, “If I get a talking-to from my cook, how can I be an arrogant person?”

The kitchen staffers in your book experience personal stress and hardships during their time serving presidents. Wright gains eighty pounds during her tenure. Washington’s enslaved chef, Hercules, has his freedom dangled in front of him and finally runs away. Did you feel like you pulled back the curtain on how difficult these roles were?

The relationship between the president and the cook varies. Washington has a complicated relationship with Hercules. Washington shuffles him back and forth between Pennsylvania and Mount Vernon to avoid Pennsylvania law that would allow Hercules to be free after six months in residency.

Washington would let him walk about town after he finished his cooking duties. Hercules could go to the opera. He even let Hercules sell leftovers out of the kitchen. And this brother’s cooking was good—he was making $5,000 a year (in current dollars) selling leftovers. But at the end of his presidency, Washington is suspicious that Hercules is going to try to escape. Rather than send him to the kitchen at Mount Vernon, he sends Hercules into the fields to do hard labor. That was too jarring for Hercules. After Hercules ran away, Washington spent a lot of time and spared no expense trying to get Hercules back.

But the poignant example to me is two enslaved women, Edith Hern Fossett and Frances Gillette Hern, who cooked for Jefferson. They were assistant cooks. These women lived most of their lives in the White House basement; their slave quarters were right off the main kitchen. They gave birth to kids in the White House basement, and some of their kids died there.

You’ll have to explain that.

Anyone who’s been in DC in July or August can understand this because DC is essentially a reclaimed swap—the White House was a seasonal residence. People would leave in late May or early June and return in the fall when the weather cooled. But Jefferson made these women stay and cook for the skeleton staff that remained, so Fossett and Hern never got to go back home to Monticello. Working in a hot kitchen during the sweltering summers in DC was no joy either. Believe it or not, in the nineteenth century, summer White House employees would sometimes get stricken with tropical diseases like malaria! There are stories of these women’s husbands escaping Monticello just to visit their wives. But Jefferson would have the men caught before they got to DC and send them back.

In terms of the modern inconveniences, traditionally White House kitchen staff has earned low pay compared to what somebody could command in the private sector. And even then, the black cooks were always paid less than the white cooks. I’d also see complaints about the long hours. The thing that bothered the cooks the most were presidents who were consistently late, and presidents who show up with guests at the last minute.

The other part is the diminished status. Ever since Jacqueline Kennedy made a change in leadership, African Americans have been assistant chefs. I don’t mean to demean that position, but 1968 is the last time you have an African American running the White House kitchen.

What did Jacqueline Kennedy do differently?

First, let’s go back to the 1800s. The cooks were primarily African American women. But during the Theodore Roosevelt administration, there was a sharp break from African American cooks having the dominant position. There was a Swedish cook vibe from 1904–1920. I don’t know what that’s about. Swedish and Irish women were running the White House kitchen. Then you get to FDR, and there was a run of black cooks for quite a while. Truman and Eisenhower have white chefs, and Eisenhower had a Filipino chef as well, Pedro Udo.

A Filipino chef!

His son is still alive; I’m trying to get in touch with him so I can interview him. But Jacqueline Kennedy was not feeling Udo because he was a military cook. She changed the standard to European food from European-trained chefs. That started a thirty-year run of European chefs running the White House kitchen. It was interrupted briefly because LBJ and the French cook that Kennedy hired didn’t get along, so he quit. LBJ brought his family cook, Zephyr Wright.

You write about the peculiar balance of the special connections these cooks had with the presidents they served, and the subjugated role these men and women often experienced in society.

Even though these presidents weren’t interested in improving the status of black people overall, I found these wonderful expressions of genuine sentiment between the presidents and their staff—celebrating family births, giving anniversary gifts. Some of these African American professionals named their kids after presidents they worked for. Presidents attended the funerals and were moved by the deaths of these cooks. You hear about deathbed farewells. It doesn’t square with the dynamics of the time.

Did your aim in writing this book change in the process?

When I started, it was about my curiosity. Then I became fueled by a fierce determination to make sure these people got adequate due. I want to correct the record and possibly be a springboard for deeper scholarship about this aspect of the presidency. I’m not going to lie: At times I was angry. I’d read the sources and I’d figure out the role that an African American played in a situation, and it’s stunning to me that they’re not even mentioned.

It underscores the arguments about culinary justice and attribution.

I was definitely thinking about that. This is one of the most stunning examples of the need for balance, to bring to light what these folks actually did. I think these African American cooks gave our presidents a window on black life. A lot of presidents chose not to open that window, but because of the ones who did, I think our country is better for it.

Adrian Miller is also the author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time.